Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast (10 page)

Read Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast Online

Authors: Edmond Boudreaux Jr.

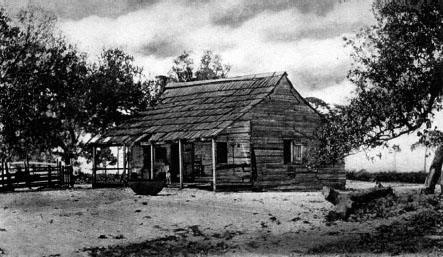

Home of Juan de Couevas on Cat Island.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

Vice Admiral Cochrane next attempted a landing at Mobile in September 1814. When one of the British vessels ran aground, the invasion of Mobile was called off. The British fleet continued west, and a new plan to make a frontal attack on New Orleans was devised. On November 7, Andrew Jackson successfully captured Pensacola and returned to Mobile on November 19. On November 22, his forces departed Mobile for New Orleans and a date with history.

On December 8, Vice Admiral Cochrane's fleet arrived at the Chandler Islands. His next move was near Cat Island and the mouth of Lake Borgue. This placed the fleet seventy miles from New Orleans, but the heavy ships and transports could go no farther. The troops would be ferried thirty miles to Pea Island and, from there, another thirty miles to Bayou Bienvenu. On December 14, five American gunboats were defeated on Lake Borgue, removing the last obstacle for the landing forces.

The British troops selected to invade New Orleans were considered the best in the world and were seasoned veterans of the wars with Napoleon and the invasion of Washington. From C.J. Forbes's letter, we know that high-ranking British officers were of the opinion that when they arrived on “the American continent that the vexatious taxes imposed upon them [the people] by the American government had so disgusted the people at large as to leave no doubt of our being received with open arms.” Forbes stated:

A representation of this effect must have gone home and can be the only means of accounting for the reason why the ministry did not send out a force with us adequate to the enterprise we were sent on. The issue has proved that the admiral's information was fallacious and the returns of our killed and wounded will convince the world that the opposition we have met with was owing to the unanimity of every class of men. In fact, not a white man of even the lowest description has joined us since we landed, nor have our generals or the admiral succeeded in obtaining information of the most trivial nature

.

As far as adequate forces, Vice Admiral Cochrane had eight thousand to nine thousand seasoned veterans to Andrew Jackson's roughly four thousand mixed forces. Jackson's force included the Seventh U.S. Infantry, a variety of militias, free blacks, Native Americans and Jean Lafitte's Baratarians.

The real problem the British had was in transporting troops. Forbes stated, “Only 1,600 men could be put on shore at once, owing to the want of boats in the fleet and the distance the troops were to be conveyed from Cat Island to within eight miles of New Orleans, about a hundred miles.” The landing of the troops occurred near Major Gabriel Villere's plantation, nine miles below New Orleans. Forbes said that the plantation was deserted and “learned from the slaves that their masters had joined the militia corps.”

As darkness fell on December 23, Major General John Keane and 1,800 British troops camped on the Villere Plantation. After learning that British forces were encamped there, Andrew Jackson left New Orleans to engage the British. Forbes continued, “No sooner, however, had daylight quitted us than we were suddenly surprised by a tremendous fire of grape and round shot from a 12 gun schooner that had dropped down unperceived by any person of the army.” The vessel was “just opposite our position but within grape range.”

While suffering many losses, Major General Keane was able to move his troops to a defendable position and began to return shots against the schooner. Within fifteen minutes, Andrew Jackson's troops had maneuvered into position opposite the British and began to fire on their positions. Forbes wrote, “We found ourselves assailed in the rear or on the flanks by about 7,000 men under General Jackson.” Of course, Jackson had nowhere near that number of troops. British forces listed 46 killed and 277 wounded, and the Americans listed 24 killed and 213 wounded. The first day's encounter ended in a draw.

Andrew Jackson took advantage of the situation and withdrew to Rodriquez Canal, near Chalmette. Here, Jackson established a line, and his men began to fortify the area of the canal. Major General Edward Pakenham, British commander, wanted to take the Chef Menteur Pass to Lake Pontchartrain. British officers convinced Major General Pakenham to move against Jackson's forces. They felt the small force would be defeated easily, and New Orleans could be taken quickly. Forbes wrote, “Reinforcements of the seventh and forty-third regiments joined us.” He continued, “The general's expectation was that the period was at hand when we were to be relieved from our unpleasant situation and get into the town.”

While Jackson was fortifying his location, the British delayed their advance. On December 28, Jackson's forces repelled a British probing attack. As the battle began, Forbes wrote, “We drove in the enemy's pickets with the impression and expected to annihilate Jackson's forces in an instant, but to our great mortification we found after pushing on about three miles that his army had entrenched itself in a strong position with its right on the river and its left resting on a swampy woods which we afterward discovered to be impenetrable.”

At this point, Major General Pakenham decided to bombard Jackson's line and force him to withdraw. He added additional ordnances of all descriptions to his battery. Then on New Year's Day, Forbes reported that the bombardment “afforded us a sight of fireworks, pop guns, mortars, and rockets such as has been seldom witnessed even in Lord Wellington's great actions in the peninsula.”

The British were ready to storm Jackson's lines. The British plan was to attack Jackson's line with the main body, made up of Major General Keane's forces and Major General Samuel Gibbs's forces. Major Gibbs was second under Major General Pakenham. Another force under Colonel William Thornton would cross to the west bank, take the American batteries and turn these guns on Jackson's position on the east bank.

The plan was in trouble from the beginning. Colonel Thornton had difficulties getting boats to move his troops from Lake Borne to the river. Still, Major General Pakenham decided to attack. Forbes had a front-row seat during the British assault and wrote, “Not one of these obstacles had been foreseen and our troops rushed on headlong till brought up by the ditch in front of the American line. They were of a nature not to be surmounted and we were constrained to fall back without reach from shot from their line and ship, with loss.”

A reenactor fires a cannon on the battlefield.

Edmond Boudreaux

.

Every aspect of the assault began to falter under the withering fire of the Americans. Several British commanders were wounded or killed. Among the wounded was Major General Pakenham. Forbes wrote, “The last resource was now to storm the lines and the day was fixed.” The British attacked Jackson's line with Major General Keane's forces and Major General Samuel Gibbs's forces. Colonel William Thornton's forces crossed to the west bank to take the American batteries.

The Battle of New Orleans began on January 8, 1815. In the heat of the battle, Major General Samuel Gibbs was taking heavy fire, and his command began to fall apart. Major General Pakenham ordered Major General John Lambert to lead the reserves onto the field of battle. As Major General Pakenham tried to rally the British forces on the field, he was mortally wounded and removed from the battlefield. Major General John Keane, seeing Major General Gibbs's forces falling apart, advanced to his aid. Major General Keane's forces began to take the bulk of the American fire. Soon the second-in-command, Major General Gibbs, was dead, and Major General Keane was wounded.

Major General Lambert was now in command. As Major General Lambert entered the battlefield, he was met by the fleeing remnants of the attack columns. In one of the few successes of the day, Colonel William Thornton had taken the American battery on the west bank, but he also needed two thousand men to hold it. At this point, the decision was to retreat. Forbes wrote:

The principal attack upon the lines failed, notwithstanding the success upon the opposite side, and the public papers will sufficiently explain to you the loss the army has met with the loss of Generals Pakenham and Gibbs and the number of regimental officers and about 2,000 men. In fact, it had the effect to depress the spirits of the army so far that General Lambert, our present general in chief, immediately after the action, determined upon a re-embarkation and began to put our wounded on board the same day

.

Forbes mentioned the suffering that had occurred during their journey and said, “Not only our prospects or prize money have vanished, but promotion also, which I fully expected would have followed success.” It was common practice to reward officers and soldiers. New Orleans was considered a rich city. An officer's share could have brought him a nice estate and the soldiers a nice payday.

Vice Admiral Cochrane and Major General Lambert sailed to Mobile and captured Fort Bowyer. As they planned to take Mobile, they received word that a treaty was agreed to and fighting should cease. The British had planned, if victorious, not to honor the terms of the treaty. Due to the American victory, they were forced to do so, and America gained the respect of the world.

CHAPTER 15

T

HE

H

ERMIT OF

D

EER

I

SLAND

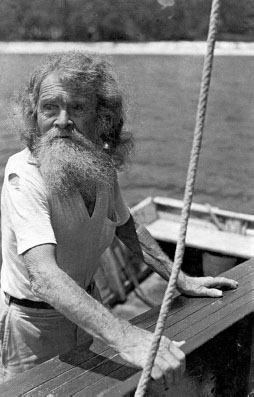

Growing up on Biloxi's Point Cadet, I learned quickly that there was an array of interesting characters living there as well. One of the most interesting characters was the Hermit of Deer Island. I can remember the first time I saw him. He was dressed in ragged clothing, with a rope for a belt, and was barefoot. His hair and beard were white, and if you had placed him in a red suit, you would have believed him to be Santa Claus. We only knew him as the Hermit of Deer Island, so who was this man?

His name was Jean Guilhot, a Frenchman who had operated a citrus grove in the Bahamas and a turtle soup cannery in Florida. He arrived in Biloxi in 1921 at forty-six years of age and began working as a barber. He met and married a widow, Pauline Lemien, who had a house on Deer Island with her son, Elmer. Elmer Lemien would later marry Rhoda Louise William and have two children, Elmer and Elaine, who were born on Deer Island. While living on Deer Island, Jean Guilhot gave up being a barber and became an oyster fisherman. A few years later, his wife died, but Guilhot continued to live on Deer Island and made his living by tonging oysters. During the 1947 hurricane, Guilhot climbed a tree and weathered the wind and water. The storm flooded the island and destroyed his home, but he built a new shack from driftwood. By this time, his skin was like leather from the sun and saltwater. He lived on a diet of cheese, fruit and various seafoods but refused to eat meat.

In early 1950, Louis Gorenflo, captain of the tour boat

Sailfish

, offered to pick up and deliver groceries to Guilhot. On a small pine sapling seventy-five feet from shore, Guilhot would place his grocery list, and during his daily tourist trips, Gorenflo would retrieve the list and return with the groceries on the next visit. At first, Guilhot would only retrieve the groceries after the

Sailfish

departed, but gradually, he began to row out and meet the

Sailfish

. Later he would sing songs in French and English for the tourists. The tourists would take his picture and throw coins into Guilhot's boat.