Lee Krasner (5 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

As a student Lenore certainly worked hard. Even years later, she was proud to state: “I earned my own car fareâ¦. I had all kinds of jobs. I painted lamp shades. I put vertical stripes on felt hats.”

27

These types of artistic odd jobs served as practice drills that prepared Lenore for technical labor later on, such as her work on the WPA during the 1930s. Many such tedious jobs depended on the labor of poorly paid young women. An immigrant she met a few years later described such subsistence-level factory jobs then available in New York, this one on the sixth floor of a large loft building just east of Washington Square. She was told to “fill in the âmodernistic' raised design on one of the parchment shadesâ¦they paid four cents a piece.”

28

Lenore preferred illustrating over needlework or other crafts identified with women's work and the Old World. Her early love of nature came in handy at Washington Irving. “We drew big charts of beetles, flies, butterflies, moths, insects, fish and so on. We would get models of a fly or butterflies in boxes with glass tops. Then it would be up to us to pick the size of sheet or composition board and the range of hard pencils and to decide how many to put on the page. And we would get anatomical assists from books. I loved doing those!”

29

She recalled, however, that she did well in all her subjects, except art. “By the time one gets to the graduation class you're majoring in art a great deal, you're drawing from a live model and so forth,” Krasner later recalled. She remembered taking “more and more periods of art.”

30

Her determination and sense of purpose were not, however, enough to win her art teacher's praises. Her originality was still too roughly formed. She possessed neither the charm nor the beauty of some of the school's earlier success stories.

The French immigrant and future actor Claudette Colbert, for example, preceded her by only five years, moving on first to study fashion design at the Art Students League.

31

When Lenore decided in her senior year to go to a woman's art school, Cooper Union, she recalled that her high school art teacher “called me over and said very quietly and very definitely, âThe only reason I am passing you in art [sixty-five was the passing mark at that time] is because you've done so excellently in all your other subjects, I don't want to hold you back and so I am giving you a sixty-five and allowing you to graduate.' In other words, I didn't make the grade in art at all.”

32

Undaunted even by harsh criticism and confident in her own abilities, Lenore remained resolute. “You had to apply with work, so I picked the best, or what I thought was the best I'd done in Washington Irving and used that to get entrance into Cooper Union. I was admitted.”

33

Her unflappable resolve and persistence would prove invaluable. She probably knew well the lesson of Rabbi Hillel, who was renowned for his concern for humanity. One of his most famous sayings, recorded in

Pirkei Avot

(Ethics of the Fathers, a tractate of the

Mishnah

), is: “If I am not for myself, then who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, then what am I? And if not now, when?”

34

To study art, Lenore had to travel each day for about an hour each way to and from East New York. Manhattan must have seemed worlds apart from the provincial life she knew in Brooklyn. This was her first taste of real freedomâwith galleries and museums to explore, including the Metropolitan Museum. There she saw the old masters and developed tastes that would last a lifetime, even after she rejected traditional art for modernism. She became particularly interested in paintings of the Italian renaissance, the Spanish masters, including Goya, and French painters such as Ingres.

With equal passion she learned to savor great art and to dance the latest steps. Unlike her older sisters, who married young, she

needed no further coaxing to move beyond her family's cramped life to one of individualism. Greenwich Village, with its lively bohemian scene, soon beckoned to her from Irving Place. It was the heyday of free love, the new woman, the Jazz Age, the fast-dancing flapper, and other thrilling new types.

While moralists attempted to prohibit “the shimmy” and other jazz dances during the early 1920s, a teenaged girl like Lenore was just getting her first taste of freedom. Drawn to the new and the chance to jettison her burdensome immigrant heritage, she was not encumbered by Victorian sexual mores. In her Jewish immigrant culture, sexuality in marriage, whether or not for procreation, was considered a positive value, not a necessary evil, as it was in Catholicism. As St. Augustine declared: “Intercourse even with one's legitimate wife is unlawful and wicked where the conception of offspring is prevented.”

35

Though premarital sex was not permitted in strict Jewish culture, the religion did not associate the human body with guilt. Judaism assumed that a woman's sexual drive was at least equal to a man's and sex within marriage was sanctifiedâfor both pleasure and procreation. In fact, the choice of a celibate life over a married life was condemned.

36

As she graduated from high school in 1925, Lenore faced a world of new freedoms and possibilities in an economy that was robust.

HREE

Art School: Cooper Union, 1926â28

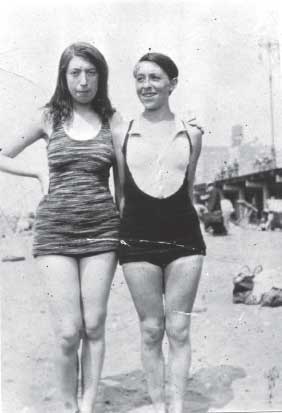

Lenore and Ruth Krasner at the beach, c. 1927.

I

N

F

EBRUARY

1926,

THE SEVENTEEN-YEAR-OLD

“L

ENA

K

RASNER

” entered the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a tuition-free college in Manhattan at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and East Eighth Street, known as Astor Place. Founded in 1859 by Peter Cooper, the school boasted that it had “a constant demand for the graduates in the commercial world.”

1

The Woman's Art School was meant to enable “young women, who expect to be dependent on their exertions for gaining a livelihood, to obtain, free of cost, a training that will fit them for useful activity in art work of one form or another.”

2

The school's supporters, visible on the long list that constituted its “Ladies' Advisory Council,” included such prominent names

as Miss Helen Frick (Henry Clay Frick's daughter), Mrs. Frederick W. Vanderbilt, and Her Highness, The Princess Viggo of Denmark (née Eleanor Green). Mrs. J. P. Morgan had also figured on the council until her recent death. The school had the attention of high society matrons, who contributed scholarship funds, money for student prizes, and even a summer art course in Paris.

Applicants were admitted as space became available, “with some preference to such as submit work showing preparatory training or decided fitness for artistic pursuits.”

3

Lenore Krasner began in midyear. That academic year the Woman's Art School enrolled 293 girls for training in design and applied arts, including fashion, furniture, illustration, interior decoration, portrait and other painting, and the teaching of art. At the end of her life, Krasner reminisced: “I do recall Cooper Union having the most magnificent Cooper-Hewitt Museum available to us, just one flight below our classroomsâwhat an enormous treat.”

4

The collection, now relocated, emphasized architecture and the decorative arts.

But another memory was less approbatory. “I also particularly remember the separation of the men and women, even with separate entrances. We never crossed paths!”

5

The Union's main men's division was an engineering school, although art classes for men were given during the evenings. Krasner never approved of separation by gender, yet, at the time, she had no other options. Typically only about two dozen women graduated in a given year.

6

The small number of graduates resulted from women dropping out because they could not produce acceptable work, as well as those who dropped out because they chose to get married, had to take a paying job, or wanted to pursue study at another school, as Krasner eventually did.

Cooper Union's emphasis on businesslike careers in the arts for women initially made it a good fit for the ambitious Krasner. The school stressed learning the craft and techniques of art, and the women's course of study was rather rigidly prescribed. Like her

classmates, Krasner began studying elementary drawing, which involved drawing from simple forms and from casts of ornaments, torsos, feet, and hands. She was also enrolled in General Drawing, which was an afternoon class open to all, and portrait painting.

Despite Krasner's previous training, her teacher for elementary drawing, sculptor and mural painter Charles Louis Hinton, still judged her work as “messy.” Hinton had been a pupil of Will Hicok Low at the National Academy of Design in New York; he had also studied in Paris with Gérôme and Bouguereau, who were famous academicians in the 1890s. Hinton's course emphasized “drawing from simple forms and casts of ornaments, blocked hands, feet, etc. Also special elementary preparation for Decorative Design and Interior Decoration for students intending to study those branches.”

7

Krasner, however, aimed to become a “fine artist,” not a “decorative artist,” and resisted this practical curriculum.

A muralist and an illustrator for children's books, Hinton was trying to maintain old-fashioned academic taste at a time when modern art was beginning to make its way into public consciousness.

8

He could not tolerate Krasner's independent spirit and casual attitudes. And for her part, this resistance came at significant risk. Students were subject to close supervision, and anyone not making fair progress was subject to dismissal. In order to advance from elementary drawing, the lowest class, a student had to advanceâand that was subject to the teacher's judgment.

9

Krasner later recounted how Hinton's course was divided into alcoves: “The first alcove, you did hands and feet of casts, the second the torso, and third, the full figure, and then you were promoted to life. Well I got stuck in the middle alcove somewhere in the torso and Mr. Hinton at one point, in utter despair and desperation, said more or less what the high school teacher had said, âI'm going to promote you to life, not because you deserve it, but because I can't do anything with you.' And so I got into life.”

10

In May Cooper Union awarded Krasner a certificate stating

that she “has successfully completed the work prescribed for the class in Elementary Drawing.” She had registered as “Lena Krasner” but managed to have them put on her certificate “Lenore,” the first name that she had chosen for herself.

11

Free from Hinton's strictures, Krasner began the fall term as one of 312 woman students.

12

Since almost all of the teachers at Cooper were men, role models for women were very scarce. Ethel Traphagen, who taught courses in fashion design, was a notable exception.

13

She had made an impact in the world of fashion and is said to have brought attention to the United States as a fashion center. She worked then on the staff of the

Ladies' Home Journal

and

Dress Magazine

. She also resurrected and depicted “costumes of Indian maidens” and collected nineteenth-century garments. Traphagen had started out at Cooper but eventually graduated from the National Academy of Design and also studied at the Art Students League and the Chase School. In 1923, she founded the Traphagen School of Design with her husband, William R. Leigh, a painter who fiercely opposed modernism.

14

Traphagen's Costume Design and Illustration was a “two years course, designed to develop the taste of its students and to fit them for immediate practical work.” The first year's focus was on “drawing and sketching the human figure in action, proportion and details; also from garments and drapery. Historic costume; color theory; dressmaker's sketches.” By the second year, the focus was on “drawing for publication in pencil, pen-and-ink, wash, color, etc. Composition and grouping of figures. General preparation for practical work.”

15

Students also began to sketch garments and drapery as well as historic costume. They studied color theory and made dressmaker's sketches. Krasner, who had enjoyed drawing fashions as a girl, came out of the course with a respect for clothing design and designers.

Krasner was interested in clothes and style. However, her own look must have appeared very relaxed to her classmates. In the February 4, 1927, issue of

The Pioneer,

the student newspaper,

the female columnist asked: Would the world come to an end if “Kitty Scholz quit believing she was the âPrincess'? Mickey Beyers favored long skirts? Betty Augonoa and Sadie Mulholland âgrew up'? Lee Krasner at last put her hair up?”

16

This is also the first documented use of Krasner's nickname, “Lee,” rather than Lena or Lenore. In a gossip column about women students, the school paper again identified her as “Lee Krasner” when it commented positively on her eyelashes.

17

Of Cooper Union, Krasner later said, “I'm surrounded by the women that are going to be artists so there's nothing unusual about women artists, it's a natural environment for me.”

18

Changing names was commonplace among Krasner's immigrant siblings. Her name appears as “Lee” on the U.S. Federal Census for 1930, so she had definitely made the switch from Lenore by that time.

19

Though some have alleged that Krasner later took the androgynous name Lee so that it would seem that her art was made by a man, her earlier use of the name in her single-sex school casts doubt on that theory.

20

At this time, Krasner was five feet five, with blue eyes, and she had developed a model's slender figure. Her hair was auburn and usually worn in a pageboy cut, just above the shoulders. Her smile was warm, though her facial features were far from classical. Greenwich Village was becoming home to women said to be sexually uninhibited, glamorous, and free. The feminists who fought for suffrage had been eclipsed by the flapper. The struggle of revolutionary women such as Emma Goldman and Crystal Eastman seemed over. With the economy booming and garrets in dilapidated buildings available at cheap rents, a bohemian existence at society's fringes became a viable option for many. Couples living freely together made traditional marriage and families look less like an inevitable destiny than a limiting choice.

Studies of the “New Woman” blossomed in the popular press. Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, wrote that having gained the vote,

“woman is now learning how to use it intelligently so as to realize the ultimate aim of the movementâabsolute equality between men and women.”

21

Meanwhile reformers such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman discussed “companionate marriage” publicly, condemning it as “merely legal indulgence” of those “who deliberately prefer not to have children to interfere with their pleasures.”

22

She excoriated those “who seek sex indulgence without marriage, and whose activities have long been recognized as so deleterious as to be called âsocial evil,'” blaming much such behavior on “that new contingent who are infected by Freudian and sub-Freudian theories.”

23

Meanwhile the Reverend Henry Sloane Coffin, president of the Union Theological Seminary, exhorted married couples to hold “to marital vows and the keeping up of appearances even though the illusions and ideals of marriage have vanished.” Coffin evoked a case in which “the wife realizes that she has married a mediocrity, or a weakling, or a scamp; the husband finds himself tied to a scold, or a bore, or a heartless worldling.”

24

Such public discourse did little to make young women like Krasner long for matrimony just when they were beginning to test freedoms newly found.

Krasner's eventual decision to avoid motherhood should be viewed in the context of those who were then insisting that “the greatest social problem of the day” was excess population. Many in this camp, such as Harry Emerson Fosdick of the Park Avenue Baptist Church, argued publicly for “the general practice of scientific birth control.”

25

This issue was closely related to the anti-immigration legislation that had passed in the early 1920s, which encouraged those who openly called for the use of eugenics to shape the population. Indeed, Fosdick described himself as “restrictionist in immigration.”

26

Krasner's own outlook was strongly cosmopolitan, having grown up in a neighborhood populated by a mix of old Dutch farmers and recent immigrants: Russian-Jewish, French, Irish, and German, and mixed-race.

27

Years later she spoke of despising

nationalistic attitudes and resented being narrowly categorized as an “American” artistâa point of view that must come from her early experiences with various cultures and her awareness of bias against minorities.

At Cooper Union, Krasner kept her eye on her professional goal. Soon after her introductory courses, she advanced to Drawing from the Antique and Fashion Design. Drawing from the Antique entailed working with plaster casts of Greek and Roman works. The students focused on drawing the human head and figure, and in the afternoons they drew in color. Lectures were required on anatomy, perspective, and the history of art.

The first term had been an awkward time for Lee, but then her prowess started being recorded not only on her transcript but also in the school paper, which listed some two dozen women who had their drawings “hung at the monthly exhibition,” Krasner's among them.

28

Given the school's vocational agenda, it is hardly surprising that Krasner quickly made a name for herself as a fine artist. By December she obtained admission to the life drawing class, for which one had to earn admission by submitting satisfactory drawings, usually in the third year. She was only in the second term of her first year. In the mornings the students drew from life, and in the afternoons they painted from life in oil. The course stressed posing, arrangement, and lighting. That December too the newspaper's women's column reported Krasner as one of the “girls who have had work on exhibition for December.”

29

She also took Oil PaintingâPortrait and art history, which was a required lecture course.