Lee Krasner (46 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

Â

B

Y THE END OF THE SUMMER OF

1962, K

RASNER WAS DISTRESSED THAT

sales of Pollock's work were disappointing despite Marlborough Gallery's international efforts. Pressured by Gibbs and Lloyd to cut prices, she declined in almost every case, preferring, she insisted, to withdraw them from the market. On September 14, Dickler even wrote to Gibbs inquiring whether the expenses he billed were “solely on her behalf.”

81

Through her attorney, Krasner kept a close watch on the Pollocks she had consigned or loaned to Marlborough.

On Christmas night 1962, while at a dinner party in East Hampton with Ronald and Frances Stein, Krasner suffered a brain hemorrhage. She insisted on telephoning Dr. Elizabeth Hubbard, who treated the incident as if it were a migraine headache. Realizing the seriousness of his aunt's condition, Stein interceded and called a nearby doctor and the police. Krasner was then rushed to Southampton Hospital. When tests disclosed a bleeding on the brain, she was transferred to Saint Luke's Hospital in New York, where she underwent surgery to remove an aneurysm in the artery that encircles the brain. Afterward she chose to convalesce at the Hotel Adams on the Upper East Side.

Sandy Friedman wrote to David Gibbs, telling him about Krasner's ordeal and its effect on her: “There has been a marked change in Lee. Before all this happened, I think she had reached a point where she was soured and fed up with the Art World.

She had devoted her life's blood to art, to Pollock; and had lived through Pollock's tragedy and its disturbing aftermath; the feuds, the jealousies, the petty politics and grasping.” He attributed her turnabout to a “flood of notes and flowers and messages of concern from almost everyoneâeven unexpected sources like Harold and May Rosenberg.”

In some ways the ordeal made Krasner easier to deal with, even if for a short time. According to Friedman, “Something inside herâher hostility, defensiveness (dare I call it paranoia?) has relented, relaxed. For the first time since I've known her, she is filled with tolerance, sympathy, even tenderness for her fellow artists and the art world in general.”

82

A week later, after seeing Lee, Fritz Bultman quipped, “Not only didn't she lose any wheels, she seems to have added a few.”

83

By February 3, Sandy was more pessimistic about Krasner, who was resting at the Hotel Adams. “Once again here with Leeâfeeling so different now: troubled by her isolation, her disconnection, the imposition of her convalescence. Everything I said in my last letter seems reversedâit's all so ephemeralâtomorrow may be entirely differentâwho knows?”

84

He added, “She doesn't know yet what has happened to her. Like an infant she feels she must start all over again from scratch. Like an infant, she must learn to walk, to relate, to be in the world. Like an infant, she knows nothing about ART, but must familiarize herself with her own bone, body, her tongue and speech, people and the world.”

85

More than two weeks passed, and Sandy, visiting Lee at the Adams, transcribed for her a letter to David Gibbs: “Once my fury against ART relented it began to waiver [

sic

] between Elizabeth Hubbard and David Gibbsâthough at the moment it seems to favor ElizabethâNo telling how I'll come out with you David.”

86

Gibbs also heard from Ronald Stein, who wrote to him on April 19, 1963, asking for his help in getting Frank Lloyd to take an interest in showing his work in his New York gallery. Lloyd had just purchased the Otto Gerson Gallery in Manhattan and

was planning to open the following fall as Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, which would feature Jackson Pollock's work. Krasner essentially withdrew her work from the Howard Wise Gallery at this time.

87

Stein described himself as “despondent” because he was “galleryless.” Krasner had already persuaded Lloyd to visit Stein's studio, from which he purchased a small sculpture. Stein reported to Gibbs that “Lee was overjoyed with [Lloyd's] response” and that he was also “delighted with his reaction and proceeded to get smashed for three days afterward.”

88

Given his aunt's experience with Pollock's alcoholism, this was a slightly ominous note.

For the summer of 1963, Krasner again settled in the Springs house, which by now, according to William K. Zinsser, writing for

Horizon,

was assuming mythic dimensions: “Jackson Pollock, fleeing the hostile New York art world, came to this isolated spot in 1946 [1945], and gradually other painters followed. As Pollock's work at last caught on, and especially after his death in 1956, the colony became almost a shrine, and so did the Pollock house where his widow, Lee Krasner, still lives and paints. Today the abstract expressionists in The Springs form a sizable clique, and they do not lack for admirersâEast Hampton is full of wealthy patrons and hangers-on.”

89

This article featured a photograph of Krasner among a diverse group of luminaries who then spent their summers on the East End of Long Island, including the actors Eli Wallach and Anne Jackson, Gwen Verdon and her husband, the choreographer-director Bob Fosse, architects Gordon Bunshaft and Peter Blake (who had collaborated with Pollock), and writers such as Jean Stafford, Helen MacInnes, and Gilbert Highet. Krasner, identified as “the widow of Jackson Pollock,” was described as “anything but Bohemian, Miss Krasner has her clothes made by America's most cerebral couturier, Charles James, and her house is tasteful and feminine. It is filled with her own paintings, but there are no longer any Pollocksâthey have become too precious and costly for

a summer house.”

90

The feature allowed that “although her style was undoubtedly influenced by her late husband's innovations and theories, it is quite distinctly her own.”

91

That summer Krasner hired a young graduate student in American history, James T. Valliere, who had written a paper on El Greco's influence on Pollock's early work. He lived and worked in a small building behind her home for the next two summers, assuring that she was not there alone. She had him begin putting together material for what she envisioned as a complete catalogue of Pollock's art. Valliere made a catalogue of all the books that had been in the Springs home before Pollock's death and conducted some interviews about Pollock with some of the people who knew him.

92

Krasner began experiencing dizzy spells, and once she tripped and fell while walking down Main Street in East Hampton and broke her right arm. She had to wear a cast, which left only her fingertips free. Undaunted, she devised a way to move her left hand around with her right fingertips, enabling her to paint. Using paint directly from the tube with a technique of spots sometimes called stippling, she managed to produce pictures such as

Eyes in the Weeds, Happy Lady, Flowering Limb,

and

August Petals.

93

In 1964, she explained: “This broken right hand which was done a year ago last summer, made me start painting with the left hand.”

94

Despite her spunk in handling impediments to her health, Krasner could not deal with male colleagues, including de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Barnett Newman, who treated her as less than equal. Of these, Newman was closest to Krasner. He and his wife had met her at the airport when she returned from Europe for Pollock's funeral, so they recognized her as a widow, but often not as an artist in her own right. It was Newman who had failed to invite Krasner to join with Pollock and the other men in the protest that led to the infamous “Irascibles” photograph.

Newman's attitudes as a Jewish man in particular reflected those Krasner had encountered when at the age of thirteen she discovered that she could not sit with her father in the synagogue. “At that point I begin to realize the differences where they separate; in the synagogue the women have to sit upstairs and the men downstairs. That was the beginning of it.”

95

Krasner never forgot the struggles she experienced trying to achieve parity as a woman and remained bitter about the morning prayer for women that she had recited daily in Hebrew in her Orthodox Jewish home, claiming, “That started up a revolution that I have not recovered from.”

96

Krasner often spoke of her “running argument with Barnett Newman” over “the role of the female in Judeaâ¦we never settled that argument.”

97

In a subsequent interview, she discussed how she had fought this ideological battle with Newman, who told her that she had missed the whole point. “I said I didn't think I missed it, I thought I had it and I objected too. But the Christian concept is basically the sameâit's Judeo-Christian; and the Moslem concept is not much better. It will take time to iron the whole thing out,” she said, using a metaphor of domesticity. “It's not just the fault of the Surrealists.”

98

Of her bout with Newman, she recalled, “We battled till he died; he said I misunderstood and I said I understood loud and clear but I objected. Then one time he asked me whether I had seen the plans for his synagogue. I asked why I should see them.” He claimed that his design would settle the argument. “âWell, where are the women in your synagogue,' I asked. âYou'll see! You'll understand!' he said. âRight on the altar!' And I said, âNever.

You

can sit on the altar and get yourself slaughtered. I want the first empty seat on the aisle.'”

99

This exchange must have taken place in 1963, when Newman first presented his synagogue model in the exhibition “Recent American Synagogue Architecture.” Apparently he drew upon Jewish mysticism and baseball for his designâin the synagogue the men sat together in a dugout. For the traditional raised plat

form (bimah), Newman substituted a raised pitcher's mound in the center of the room. “The synagogue is more than just a House of Prayer,” Newman explained. “It is a place, Makom, where each man can be called up to stand before the Torah to read his portionâ¦. Here in this synagogue, each man sits, private and secluded in the dugouts, waiting to be called, not to ascend a stage, but to go up on the mound whereâ¦he can experience a total sense of his own personality before the Torah and His Name.”

100

While Krasner might have found the baseball metaphor acceptable, Newman's focus on the men's role in the synagogue was just the kind of thinking that had alienated Krasner in the first place. She had enthused instead over Mr. Walrath, her elementary school teacher, who allowed the boys and girls to play baseball together. Krasner always wanted to be “a player.”

Around this time, Krasner met the art critic Barbara Rose, who recalled that the critic and dealer John Bernard Myers and his partner, the theater director Herbert Machiz, brought Lee over to meet her. Rose, then still in her twenties, remembered how Krasner adored her young daughter Rachel and made paper bag puppets for her. The two women began to meet each other over lunch. Rose recalled that Krasner was then “very isolated,” very “Depression-oriented,” and often served her leftovers.

101

The two enjoyed sharing gossip, and an enduring friendship was forged. Rose admired Krasner's work and had seen her shows at the Howard Wise Gallery. She heard Krasner's bitter and colorful stories about the men who ran the art world, and before long, she began to write about Krasner, including her in a book,

American Art Since 1900,

and in such popular publications as

Vogue

and

New York

magazine, raising Krasner's public profile and eventually winning her trust for larger projects.

102

During the summer of 1964, Terence Netter, a handsome Jesuit priest then in his thirties, arrived in East Hampton with his teacher Alex Russo and some younger students to study painting. They were part of a master's in fine arts program at the Corcoran.

The group made studio visits to John Little, Conrad Marca-Relli, and then Lee Krasner. She took them into her house, where

The Eye Is the First Circle,

nearly sixteen feet wide, was hanging in the large open dining room. Netter recalls that he looked at it and said to her, “That's your painting. What does it make you feel?” “It scares the shit out of me,” she replied. Netter was enchanted and responded, “I like you. Can we have dinner tonight?” Krasner accepted. It was “friendship at first sight,”

103

the beginning of a strong bond that would endure through major changes in his life and until the end of hers.

Krasner found Netter fascinating. His father was Jewish and his mother was Catholic, and he had put away his desires to become an artist at the age of eighteen to join the priesthood. He was sent to study theology in Austria and France, where he became fluent in German and French. Krasner, who had already found Catholicism of interest in her conversations with Alfonso Ossorio, found that Netter understood the spiritual side of creativity. For him, Krasner “had a very fine mind” and was “absolutely authentic.”

104

He explained, “Lee was almost like a nunâso single-minded and obsessed with the art world that she really didn't live in this worldâ¦. I'm certain Lee believed in God, but she wasn't someone who thinks a âreligious' painting is one which has religious imagery. Rather, she was interested in the whole notion of art as a sublime statementâMan trying to get beyond this world to reach some transcendental reality.”

105

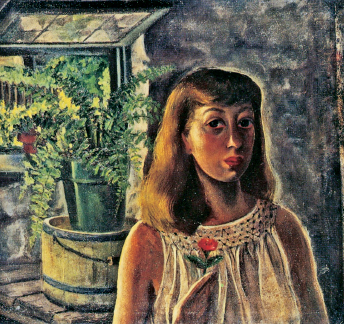

Krasner submitted this work from the previous summer to the committee at the National Academy of Design in order to be allowed to work from life models instead of casts. She was promoted in January 1929. CR 3

Self-portrait

, 1928, the Jewish Museum, New York.

In this self-portrait, Krasner depicted herself in half-light, posing in the Brooklyn basement where she lived. Her friend, Eda Mirsky, acquired the painting and later presented it to t he Metropolitan Museum of Art. CR 1

Self-portrait

, c. 1929, oil on canvas, 30½ x 32½ in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Eda Mirsky Mann, 1988.

From 213 West Fourteenth Street, a building that offered access to the roof, Krasner briefly painted in a realist style close to that of Edward Hopper, who, two years earlier, painted

City Roofs

, depicting a similar view from his own roof. CR 17

Fourteenth Street

, 1934, oil on canvas, 24¾ x 21¾ in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

Krasner admitted that some of her early paintings had “a slight touch of Surrealism.” Here she has already discovered the work of Joan Miró. CR 24

Gansevoort II

, 1935, 25 x 27 in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

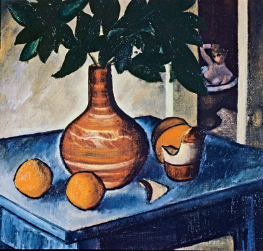

Krasner's aim is intentionally erotic, signaled by the Cézannesque still lifeâtwo ripe oranges in the foreground evoke the nude's round breasts and the broken pottery, like the broken eggs in Greuze's still life, the woman's lost virginity. CR 32

Bathroom Door

, 1935, oil on linen, 20 x 22 in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

Her flat ground, as well as the placement and shapes of the separate objects tilted toward the picture plane, evoke Matisse's

Gourds

of 1916, acquired by the Museum of Modern Art the same year she painted this homage. CR 33

Untitled (Still Life)

, 1935, oil on canvas, 20 x 28 in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

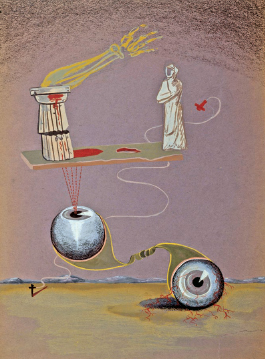

Krasner borrowed the motif of eyes from examples of fantastic art by Grandville and Redon, both featured in the MoMA exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism” that opened in 1936. CR 31

Untitled (Surrealist Composition)

, c. 1936â38, mixed media on blue paper, 12 x 9 in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

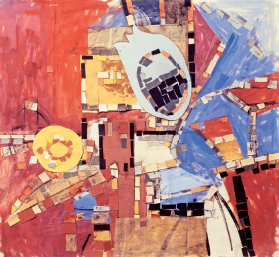

Working from a still-life setup at the Hofmann school, Krasner allowed the objects to dissolve into the surrounding space, creating an abstract composition animated by vibrations of colored shapes pushing and pulling against one another. CR 39

Untitled (Still Life)

, 1938, oil on paper, 19 x 25 in. Pollock-Krasner Foundation, New York. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.

Mondrian's geometric abstractions appealed to Krasner, who sometimes worked in a similar palette limited to the primary colorsâred, yellow, and blueâplus black and white. CR 95

Red, White, Blue, Yellow, Black,

1939, oil on paper with collage, 25 x 19

1

/

8

in. Thyssen-Bornemìsza Collections.

With its jazz rhythm, emphasis on primary colors, and use of bits of colored paper to achieve an optical effect that vibrates, this seems unlikely to be related to anything but Mondrian's work. CR 97

Mosaic Collage

, c. 1942, paper collage on paper, 18 x 19½ in. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of the Robert Miller Gallery.