Lee Krasner (18 page)

Authors: Gail Levin

A week later, Igor sent Lee a note telling her, “I have a place to exibit [

sic

] Joans [

sic

] portrait so will you send it to me together with the strecher [

sic

]. When you roll it up, roll it with the fase [

sic

] outside. Send by American Express.” He wanted it right away and asked that she also send him six black soft Conté sticks collect. He added: “I'm righting [

sic

] to Nat that if you need any money and if he has any to give to you. There is not very much to say

about this place it is raining and my parents are much purer [

sic

for

poorer

] then [

sic

] I expected. (father is crazy) Mother is sick.”

92

By then Krasner had moved from 44 East Ninth Street to a cheaper place a block away at 51 East NinthâMercer's former apartment. A few months later, Krasner had discovered the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud's

A Season in Hell,

in a new translation by Delmore Schwartz that was published on November 5, 1939. She enlisted her friend Byron Browne to put the following lines on her studio wall because she liked his handwriting, which was bold and clear.

93

To whom shall I hire myself out? What beast must one adore? What holy image attack? What hearts shall I break?

What lie must I maintain?

In what blood must I walk?

94

The words were entirely in black paint except for

“What lie must I maintain?”

in blue. Krasner would have been drawn to the title,

A Season in Hell,

at the moment that Schwartz's translation appeared, for it seemed to capture what she had been going through between unemployment and Pantuhoff's abrupt departure. In fact someone may have recommended Rimbaud's poem to her because it speaks about departure, suffering, and anger. Rimbaud even wrote denying a departureâjust what Krasner did at first when trying to deal with Pantuhoff's absence.

Krasner's interest in these lines ran deep, as Eleanor Munro discovered when she asked Krasner about them in an interview. “She [Krasner] is not about to go back and expose those feelings now. But clearly there was a bond felt during those fraught and frustrating years with another artist [Pantuhoff] who had begun in full hopes only to find himself negating his gifts âin the hell-fires of disgust and despair.'” Munro had stumbled upon pain Krasner suffered from Pantuhoff's self-destructive habits, espe

cially his excessive drinking, but also his sudden abandonment of their relationship, their “togetherness.”

95

Krasner may also have been thinking about the consequences of choosing to live the artist's bohemian lifestyle with its copious consumption of alcohol. This might have been how she interpreted the line “What beast must one adore?” for herself. Certainly Pantuhoff's behavior at times qualified as that beast, beyond her control.

It is not certain where Krasner first encountered Rimbaud, but the poet is a logical extension for someone who admired the work of Poe. During this time art talk, exhibitions, and publications were discussing André Breton and his Surrealist colleagues, who believed that the unconscious mind was a source of inspiration and found examples in the work of earlier artists and poets, including Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Rimbaud. Because we know that Krasner made art influenced by images in the 1936 MoMA show “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism,” it is likely that she once had a copy of the show's catalogue, which discusses “the revolutionary aspects of Rimbaud.”

96

That description alone was enough to provoke the curiosity of a woman who wanted to be part of what was new and revolutionary.

Harold Rosenberg, who shared her interest in Rimbaud, quoted the first two phrases of the same passage in a 1938 article for

Poetry

magazine entitled “The God in the Car,” although his translation is not the one Krasner used, for she used more lines and did not know French.

97

At the time Delmore Schwartz's translation of Rimbaud's

A Season in Hell

was published, both he and Clement Greenberg were writing for

Partisan Review,

so Krasner could have met Schwartz through her friendship with Greenberg.

98

The Rimbaud lines offered some solace, but Krasner was stunned by losing Igor, with whom she had made her life over the last decade. Other friends tried to cheer her up. That same fall,

Krasner accompanied John Little to an artists' costume ball given by the management of a new Viennese restaurant on East Seventy-ninth Street. As a publicity stunt, the restaurant invited all the students from the Hofmann School. “I invited a few students from the school to meet at my studio and go uptown together,” recalled Little. “Lee was my date. She wore gray robes, a carrot-red wig made of yarn, and carried in her hand a real Madonna lilyâthe Raphael Madonna replete! I went as Mephistopheles [the name of the demon in the Faust legend]. As soon as all our friends arrived we had a few drinks and went off to the ball well prepared.” For Little, it was “a memorable evening; and we danced until dawn.”

99

On November 23, 1939, just before the WPA hired Lee again, Igor wrote her from Miami Beach, telling her that he had received her air mail. “No I'm quite all right there is nothing rong [

sic

] I received your package for which I thank you very much. Sorry to hear you have not got your job back.”

100

On February 26, 1940, he wrote again from West Palm Beach. “You ask me in the last letter if I'am [

sic

] coming back to New York? I dont think so I'am [

sic

] leaving for Texas soon where I hope to find work. About Nat and the money He rought [wrote me] and said that he did not have in mind paying me money but only building phonograp [

sic

].” He then asks her to send “C.O.D.” all the things that he had left behind in New York: his leather jacket, shirts, and his sketch stool. If she doesn't want the large canvases he left behind, he requests that she give them to Hans Hofmann.

101

This definitive break left Krasner bereft after living so long together and sharing so much. After all, they had given the impression that they were married, perhaps not only to others. Socially this was tantamount to a divorce. On March 7, 1940, Igor wrote again, noting that he had received her letters and the portrait that he had asked for. He requested her once again to send all of his things, enclosing a long list with such essentials as his “Burrbary coat [

sic

],” Mexican shoes, his blue raincoat, his underwear, and his “large palett [

sic

].” He concluded only “I hope you are well.”

Apparently, when he had left for Florida, he had intended to return. Perhaps his family, who had refused to meet Krasner, had helped to convince him not to go back to her.

On March 19, Igor wrote again, acknowledging having received her letter about his things and “about Brodivish [

sic

].” He informed her that he wrote to Brodivish for information and tells her “the tools I imagine your father would lick [

sic

] to have. I hope you well Igor Will you do this as soon as possible? please.”

102

On the back of the envelope, the word

idiot

is scrawled. The handwriting is Lee's.

By March 24, 1940, Pantuhoff had yet to move to Texas. Instead he was partying with the Social Register set and clearly using his parents' social connections in Russian high society in exile. The

New York Times

even reported his presence in Palm Beach at a Russian dinner given by Prince Mikhail A. Goundoroff for William C. Bullitt, the United States ambassador to France.

103

One can only imagine how Krasner must have felt if she read this notice or heard about it from friends. Earlier that month the

Times

had reported that “Mrs. Evelyn McL. Gray had a cocktail party at her [Palm Beach] home, where the portrait of her daughter, Miss Elise Phalen, by Igor Pantuhoff, was shown for the first time.”

104

On March 28, Igor sent Lee a postcard from West Palm Beach to acknowledge that he had received hers. “I ges [

sic

] I did not explain that I need my things now. Will you please send them as soon as possible. Igor.”

105

By this time, Pantuhoff had clearly decided to abandon hopes of a career in the New York art world. It seemed like he just wanted the easier lifestyle of a society portraitist.

Using his connection to Fritz Bultman, whom he knew from the Hofmann School, Igor went on to New Orleans. There, in 1940, he painted the portraits of Bultman's mother and, working from a photograph, his deceased grandfather, Tony Bultman. From New Orleans Igor moved on to high society in Natchez, Mississippi. He migrated from plantation to plantation, painting

as he went, sometimes “servicing” the southern ladies as well.

106

The young Dutch painter Joop Sanders recalled that by the late 1940s, Igor was known as “a walker,” someone who escorted rich women.

107

Fred Bultman, Fritz's father, helped Igor make connections in Natchez.

108

He hit it off with Leslie Carpenter, a banker who lived at Dunley Plantation. The two men began to “hunt, drink, and womanize” together until Igor had a hunting accident. He moved on then, “everybody's houseguest and bed mate,” while the menfolk were otherwise engaged. He painted the dowager empress of the garden club, Catherine Grafton Miller. Attentive to both high style and telling detail, Igor endowed his female subjects with the same kind of flattering small waistline that John Singer Sargent had painted in his idealized portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner in 1888.

Igor did not enjoy his own family's confidence. His father wrote to Igor's brother Oleg, Jr.: “one must be very careful in talking with Igor, as he gets everything mixed up. Right now he is in New Orleans, I hope painting.”

109

Igor not only put a greater physical distance between himself and Lee, but he also moved light-years away from modern art and the New York scene. If Krasner had so far held on to hope that he would come back soon and that they would resume the life that they had shared, she finally had to see that he was not capable of either being the man or the artist she needed. The time had come to move on.

EVEN

Solace in Abstraction, 1940â41

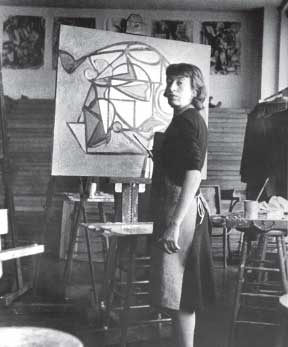

Lee Krasner working at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts, c. 1940; on the easel is an early state of

Untitled, 1940â43

(CR 133).

W

ITHOUT

I

GOR

, K

RASNER MAY WELL HAVE FOUND THAT

their old coterie of male artists treated her differently. She liked Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky, but it is not clear that they respected or recognized women artists as more than sexual, if not life, partners. Around this time, Krasner began taking an active interest in the American Abstract Artists (AAA), an artist-run organization that included married artist couples such as Krasner's friends Rosalind Bengelsdorf and Byron Browne and Gertrude “Peter” Glass and Balcomb Greene. This assured respect for women as artists and equals. Formed in 1936 exclusively for artists to show their work together, its founders

included a number of Krasner's other acquaintances and friends from her days at the academy, the WPA, and the Hofmann SchoolâGeorge McNeil, Burgoyne Diller, Harry Holtzman, and Ibram Lassaw.

The AAA supported “Peace,” “Democracy,” and “Cultural Progress,” though according to George L. K. Morris, an abstract artist and ideological leftist, the organization opposed the social realist art supported by the American Artists Congress.

1

From 1937 to 1943, Morris wrote for

Partisan Review,

which he helped fund and edit and for which he was the first art critic; the

Review

became identified by many as espousing “Trotskyism,” since, like Morris, it was anti-Stalinist.

Krasner took action with the AAA on April 15, 1940, when the organization picketed the Museum of Modern Art, which had rejected the AAA's request to show the group's abstract art. “We were picketing the Museum of Modern Art and were calling for a show of American paintings and George L. K. Morris and I, when we knew that there was a trustee meeting, were given the task of handing [each] one of them, as they left the building, a leaflet saying, âShow American Paintings.'”

2

The handouts, designed by fellow AAA member Ad Reinhardt, asked: “How Modern is the Museum of Modern Art?” It was a slogan that the

New York Times

called the “battle cry” of the “Avant Garde.” The pamphlet proclaimed, “In 1939 the museum professed to show art in our timeâwhose timeâSargent, Homer, Lafarge and Harnett? Or Picasso, Braque, Léger and Mondrian? Which Time?”

3

The

Times

reporter also described “a handbill passed out to about a thousand artists who, by invitation, entered the museum at 11 West Fifty-third Street for a preview. Even the curlicue type in which the challenge was set expressed the contempt of the rebels, for it conjured up the velvet antiquity and the theatrical posters of the Gay Nineties.”

4

The show that set off the protest was called “P.M. Competition: The Artist as Reporter” and ran from April 15

to May 7, 1940. Organized by

P.M.,

“a projected afternoon tabloid newspaper,” the show was meant to attract publicity by searching for “new talent in the great tradition of Daumier, Cruikshank, Rowlandson, Winslow Homer, Nast, Luks, and Glackens.”

5

Many bystanders mistakenly thought that the museum's show of Italian Renaissance painting, which had been sent to the United States because of the war, had caused the artists' protest, but Morris explained the picketers' motive: “What they really were angry about was the show of drawings from the newspaper

P.M.;

Marshall Field [heir to the department store fortune and a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art] wanted them shown. American Abstract Artists felt that if the Museum of Modern Art had space for newspaper sketches it certainly wasn't true that they had no space for abstract American art.”

6

Field had hoped that the MoMA show would attract effective political art for the tabloid paper

P.M.,

which he financed. Starting in June 1940, Ralph Ingersoll published the tabloid in New York for eight years. It attracted radical journalists and feature photographers as notable as Weegee (Arthur Fellig) and Margaret Bourke-White, and illustrators such as Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) and Crockett Johnson, both of whom became beloved for their children's book illustrations. At the time, Geisel was trying to drum up support for aiding Britain, especially because he believed war with Nazi Germany was inevitable.

7

The first issue of

P.M.

had not yet appeared when the protested show was held.

Krasner believed that an artist had to struggle againstâand also depend onâthe Museum of Modern Art. The museum was “like a feeding machine. You attack it for everything, but finally it's the source you have to make peace with. There are always problems between the artists and an institution. Maybe that's healthy. You need the dichotomyâartist/museums, individual/societyâfor the individual to be able to breathe.”

8

Even more important than the MoMA was the pantheon of French artists. “We acknowledged the School of French Paintingâthe Paris School

of painting as the leading force and vitality of the timeâ¦. One didn't miss a Léger showâ¦. But the giants were unquestionably Matisse and Picasso.”

9

Krasner's ultimate evaluation of American Abstract Artists was somewhat critical: “I found them a little provincial after a bit in so far as they became exclusive; that is to say at one pointâI was then working with Hofmann; I suggested that he be invited to lecture or do something and they turned that down. I wanted to know why they didn't include [Alexander] Calder, for instance, who was American, and so forth. And there was a no-no to that, so they were already ruling in and out certain things.”

10

This exclusivity was definitely a cause for irritation. “I can remember having some hair-splitting fights within my avant-garde group because I thought we were getting a little provincial and wanted to expand its dimension,” she recalled. “Provincial in being a closed shop, as any group tends to become no matter what it is called.”

11

Despite her complaints, Krasner was happy meeting with the AAA once a week. “Their sole purpose was to put up a show once a year at the Riverside Museum and if you paid your dues and were a member you would put up two or three paintings depending on how much space one hadâ¦. You did submit work to be accepted [to AAA]. Once you were accepted that was it. You did your own selection of what went in.”

12

Krasner showed in AAA's Fourth Annual group show in June 1940, which was held at the Fine Arts Building at 215 West Fifty-seventh Street. Jerome Klein, writing in the

New York Post,

poked fun at the group. “American Abstract Artists, the national organization of adherents to squares, circles, and unchecked flourishes, are holdingâ¦their fourth exhibition.” He listed Lenore Krasner as a participant, making this her first published notice as a professional.

13

In the

New York Times,

Edward Alden Jewell panned the show, declaring, “Most of this non-representational art is instinct with academicism of its own particular brand.”

14

The summer of 1940 was hot, and Krasner was stuck working in New York. She read Carl Jung's

Integration of Personality,

about which she later remarked, “I thought it was fabulous, and I thought how marvelous, you know, that he speaks in my language, even though it has nothing to do with artâuntil he gets to the point where he starts talking about painting, where he starts analyzing some of his patients' drawings. And that was for the birds; I lost interest in Jung instantly.”

15

While Lee was alone in the city, her old Hofmann School crowd was on their breezy hillside in Provincetown, wondering about Lee. George Mercer wrote that Mercedes Carles was asking about her, whether she would come up again; Hofmann and his wife, Miz, and Fritz Bultman also sent greetings.

16

Despite her friends' affection, Krasner seems to have told someone she had imagined ending her life, because it prompted Mercer to write to her from Brookline, Massachusetts, on November 24, 1940, referring to “her projected trip up the river” (presumably the river Styx). He proposed, breezily, “Why not wait for me? Maybe we'll get some publicity out of it and a couple of sweet-scented pine coffins!” Mercer's jocular vein shows that he trusted that she was too tough to let self-pity win out.

Mercer admitted that he had been wondering whether the month would bring Krasner to Provincetown and told her that he had sold his soul “to the bitch-goddess of success.”

17

Mercer was referring to his recent commitment to work for a National Defense Project to do camouflage work. “I am the artist, or one of the artists who has been placed in the den of scientist lions and must not be devoured but must teach science the gentle way of art. It's the same old plot about which many stories have been told as perhaps you know.”

18

While Mercer compromised his artistic goals by working on camouflage, Krasner had to continue to work on finishing other artists' mural designs for the WPA. She was glad to have the income, but she longed to create her own abstract mural, more in

keeping with the abstract images she exhibited with the AAA. She had watched enviously as Gorky produced his abstract but metaphoric mural

Aviation

for the administration building at Newark airport in 1939â40. She also saw that some of the men in the AAA had been given the opportunity to design abstract murals, among them her old pal from the academy Ilya Bolotowsky, who had first designed one for the Williamsburg Housing Project in 1936â37 and then another for the Hall of Medical Science at the New York World's Fair in 1938â39, for which de Kooning also designed an abstract mural.

Finally, in 1940, Krasner was given a chance to design an abstract mural for the WPA, but she never got to paint it because the project ended just after she had produced the studies for it. All that remains of her designs is a photograph of a lost work and some small studies executed in gouache on paper. Her combination of red, yellow, and blue with black, white, and gray was inspired by Mondrian. Her shapes were hard-edged but biomorphic, suggesting the influence of Miró and Picasso. The forms are ambiguousâcalling to mind both an artist's palette and musical notes or instrument parts.

In 1941, Krasner submitted a sketch for an abstract mural at the radio station WNYC, which they accepted and commissioned for Studio A, then located on the twenty-fifth floor of the Municipal Building in downtown Manhattan. Other early abstract murals at the station had been produced by Stuart Davis, John Von Wicht, Louis Schanker, and Byron Browne. Working at the Hofmann School, Krasner adapted her abstract study from a still life on a table, although only few original elements are easily recognizable. Once again, she utilized primary colors along with black, white, and gray. Before she could execute the mural, she was taken away from the project to join the war effort. Instead of abstractions for walls, the government needed propaganda posters and designs for camouflage.

The last days of the WPA were upon Krasner and her friends.

Gerome Kamrowski, an artist who was then working on the mural project with Byron Browne, Ilya Bolotowsky, and Krasner, recalled, “One time we went out to Flushingâit was the second year of the [1939â40] World's Fair.

19

The idea was that the murals were starting to fade and it was cheaper to use us than house painters. But nothing came of it. We just walked around looking at the place. On the way back [John] Graham was on the train carrying this large object like a babyâit was a beautiful piece of African sculpture that he had gotten from the Belgian pavilion. I was sitting next to Gorky and Graham opposite.”

20

Kamrowski did not make clear whether Krasner was on that particular excursion, though he mentioned her in the same interview. It's not likely that she was, because she only remembered meeting John Graham for the first time in late 1941. However, Krasner had already read Graham's book,

System and Dialectics of Art,

published in 1937, and had liked Graham's emphasis on Picasso, but also that he had introduced so-called primitive, non-Western tribal arts as a concept for artistic consideration.

21

After the outbreak of war, a number of European modernists, and AAA favorites, fled wartime Europe for New York. Among them was Mondrian, who, at the age of sixty-eight, had been afraid to cross the Atlantic. He had left London on October 3, 1940, by convoy ship in the midst of the blitz. Not long after Hitler came to power, Mondrian discovered that he was on Hitler's list of those who made

entartete Kunst,

or so-called degenerate modern art. Having already had to abandon his paintings in Paris during World War I, Mondrian, who had been living in Paris since 1919, left for London in September 1938, when the Spanish Civil War was raging and wider conflict seemed inevitable. Only after a bomb exploded in the building next to his London studio did Mondrian urgently leave for New York.