Leaves of Grass First and Death-Bed Editions (83 page)

BOOK: Leaves of Grass First and Death-Bed Editions

11.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Universal as are certain facts and symptoms of communities or individuals all times, there is nothing so rare in modern conventions and poetry as their normal recognizance. Literature is always calling in the doctor for consultation and confession, and always giving evasions and swathing suppressions in place of that “heroic nudity”

cc

on which only a genuine diagnosis of serious cases can be built. And in respect to editions of “Leaves of Grass” in time to come (if there should be such) I take occasion now to confirm those lines with the settled convictions and deliberate renewals of thirty years, and to hereby prohibit, as far as word of mine can do so, any elision of them.

cc

on which only a genuine diagnosis of serious cases can be built. And in respect to editions of “Leaves of Grass” in time to come (if there should be such) I take occasion now to confirm those lines with the settled convictions and deliberate renewals of thirty years, and to hereby prohibit, as far as word of mine can do so, any elision of them.

Then still a purpose enclosing all, and over and beneath all. Ever since what might be call’d thought, or the budding of thought, fairly began in my youthful mind, I had had a desire to attempt some worthy record of that entire faith and acceptance (“to justify the ways of God to man” is Milton’s well-known and ambitious phrase) which is the foundation of moral America. I felt it all as positively then in my young days as I do now in my old ones; to formulate a poem whose every thought or fact should directly or indirectly be or connive at an implicit belief in the wisdom, health, mystery, beauty of every process, every concrete object, every human or other existence, not only consider’d from the point of view of all, but of each.

While I can not understand it or argue it out, I fully believe in a clue and purpose in Nature, entire and several; and that invisible spiritual results, just as real and definite as the visible, eventuate all concrete life and all materialism, through Time. My book ought to emanate buoyancy and gladness legitimately enough, for it was grown out of those elements, and has been the comfort of my life since it was originally commenced.

One main genesis-motive of the “Leaves” was my conviction (just as strong to-day as ever) that the crowning growth of the United States is to be spiritual and heroic. To help start and favor that growth—or even to call attention to it, or the need of it—is the beginning, middle and final purpose of the poems. (In fact, when really cipher’d out and summ’d to the last, plowing up in earnest the interminable average fallows of humanity—not “good government” merely, in the common sense—is the justification and main purpose of these United States.)

Isolated advantages in any rank or grace or fortune—the direct or indirect threads of all the poetry of the past—are in my opinion distasteful to the republican genius, and offer no foundation for its fitting verse. Establish’d poems, I know, have the very great advantage of chanting the already perform‘d, so full of glories, reminiscences dear to the minds of men. But my volume is a candidate for the future. “All original art,” says Taine, anyhow, “is self-regulated, and no original art can be regulated from without; it carries its own counterpoise, and does not receive it from elsewhere—lives on its own blood”—a solace to my frequent bruises and sulky vanity.

As the present is perhaps mainly an attempt at personal statement or illustration, I will allow myself as further help to extract the following anecdote from a book, “Annals of Old Painters,” conn’d by me in youth. Rubens, the Flemish painter, in one of his wanderings through the galleries of old convents, came across a singular work. After looking at it thoughtfully for a good while, and listening to the criticisms of his suite of students, he said to the latter, in answer to their questions (as to what school the work implied or belong‘d,) “I do not believe the artist, unknown and perhaps no longer living, who has given the world this legacy, ever belong’d to any school, or ever painted anything but this one picture, which is a personal affair—a piece out of a man’s life.”

“Leaves of Grass” indeed (I cannot too often reiterate) has mainly been the outcropping of my own emotional and other personal nature—an attempt, from first to last, to put a Person, a human being (myself, in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, in America,) freely, fully and truly on record. I could not find any similar personal record in current literature that satisfied me. But it is not on “Leaves of Grass” distinctively as literature, or a specimen thereof, that I feel to dwell, or advance claims. No one will get at my verses who insists upon viewing them as a literary performance, or attempt at such performance, or as aiming mainly toward art or æstheticism.

I say no land or people or circumstances ever existed so needing a race of singers and poems differing from all others, and rigidly their own, as the land and people and circumstances of our United States need such singers and poems to-day, and for the future. Still further, as long as the States continue to absorb and be dominated by the poetry of the Old World, and remain unsupplied with autochthonous song, to express, vitalize and give color to and define their material and political success, and minister to them distinctively, so long will they stop short of first-class Nationality and remain defective.

In the free evening of my day I give to you, reader, the foregoing garrulous talk, thoughts, reminiscences,

As idly drifting down the ebb,

Such ripples, half-caught voices, echo from the shore.

Such ripples, half-caught voices, echo from the shore.

Concluding with two items for the imaginative genius of the West, when it worthily rises—First, what Herder taught to the young Goethe, that really great poetry is always (like the Homeric or Biblical canticles) the result of a national spirit, and not the privilege of a polish’d and select few; Second, that the strongest and sweetest songs yet remain to be sung.

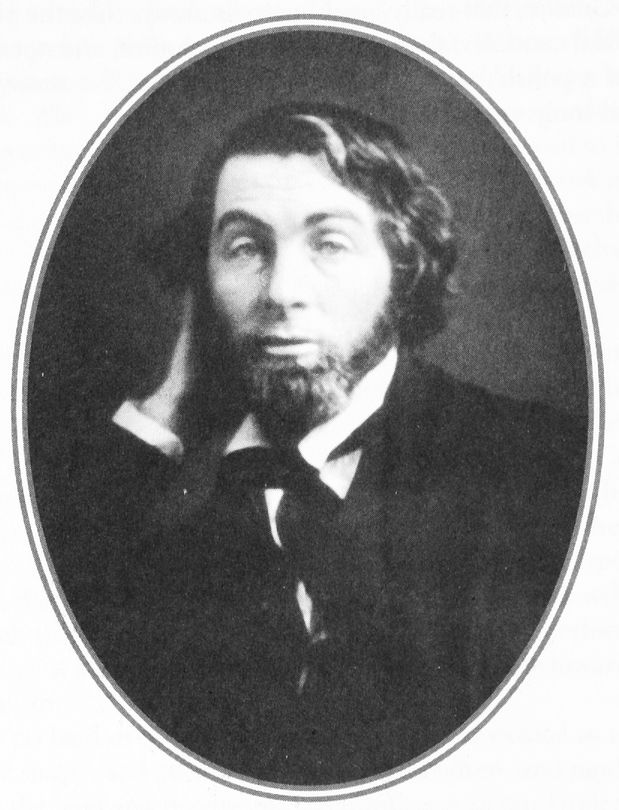

As a dandy—29 years old, 1848, photo taken in New Orleans, Louisiana,

by an unidentified photographer. Courtesy of the Walt Whitman House,

Camden, New Jersey, and the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association,

Huntington, New York. Not officially in Saunders, but sometimes

referred to as Saunders #1.1.

by an unidentified photographer. Courtesy of the Walt Whitman House,

Camden, New Jersey, and the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association,

Huntington, New York. Not officially in Saunders, but sometimes

referred to as Saunders #1.1.

ADDITIONAL POEMS

Poems Written before 1855

Poems Excluded from the “Death-bed” Edition

(1891-1892)

(1891-1892)

Old Age Echoes

(1897)

(1897)

INTRODUCTION TO ADDITIONAL POEMS

Whitman published the poems in this section outside of the First Edition (1855) or culminating edition (1891-1892) of Leaves

of

Grass. “Poems Written before 1855” includes all the poems Whitman published during the so-called “seed-time of the

Leaves”;

these twenty-three poems date from 1838 to the early 1850s. “Poems Excluded from the ‘Death-bed’ Edition” gathers the works published in other editions of Whitman’s poetry but dropped from the “Death-bed” Edition of

Leaves of Grass

(often cited as the “definitive” and “complete” edition, though it by no means includes all of Whitman’s poetry). The

“Old Age Echoes”

section contains a collection of thirteen poems that first appeared in the 1897 edition of

Leaves of Grass.

Whitman’s literary executor, Horace Traubel, claimed to have received Whitman’s consent to publish this collection.

of

Grass. “Poems Written before 1855” includes all the poems Whitman published during the so-called “seed-time of the

Leaves”;

these twenty-three poems date from 1838 to the early 1850s. “Poems Excluded from the ‘Death-bed’ Edition” gathers the works published in other editions of Whitman’s poetry but dropped from the “Death-bed” Edition of

Leaves of Grass

(often cited as the “definitive” and “complete” edition, though it by no means includes all of Whitman’s poetry). The

“Old Age Echoes”

section contains a collection of thirteen poems that first appeared in the 1897 edition of

Leaves of Grass.

Whitman’s literary executor, Horace Traubel, claimed to have received Whitman’s consent to publish this collection.

The reader is thus presented with all the poems that Whitman approved of publishing—

allegedly

approved of, in the case of

Old Age Echoes

—at some time during his life. Spanning almost sixty years and ranging widely in quality, the poems are interesting not only in their own right, but also for Whitman’s reasons for excluding them from the definitive canon of the “Death-bed” Edition.

POEMS WRITTEN BEFORE 1855allegedly

approved of, in the case of

Old Age Echoes

—at some time during his life. Spanning almost sixty years and ranging widely in quality, the poems are interesting not only in their own right, but also for Whitman’s reasons for excluding them from the definitive canon of the “Death-bed” Edition.

Musing about “long foreground” of

Leaves of Grass

in his 1855 congratulatory letter to Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of the first readers to express curiosity about Whitman’s beginnings as a poet. What had Whitman written before 1855 that hinted of such great things to come? Determined to create a myth of his origins, Whitman did what he could to “cover his tracks”: He destroyed significant amounts of manuscripts and letters upon at least two occasions and frequently reminded himself to “make no quotations, and no reference to any other writers.—Lumber the writing with nothing.”

Leaves of Grass

in his 1855 congratulatory letter to Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of the first readers to express curiosity about Whitman’s beginnings as a poet. What had Whitman written before 1855 that hinted of such great things to come? Determined to create a myth of his origins, Whitman did what he could to “cover his tracks”: He destroyed significant amounts of manuscripts and letters upon at least two occasions and frequently reminded himself to “make no quotations, and no reference to any other writers.—Lumber the writing with nothing.”

Sensitive to the public’s curiosity concerning his development as a poet, but aware that much of his juvenilia was readily available in old newspapers, Whitman decided to publish some of his early pieces in an appendix to

Collect

(1882) entitled “Pieces in Early Youth, 1834-‘42.” “My serious wish were to have all those crude and boyish pieces quietly dropp’d in oblivion—but to avoid the annoyance of their surreptitious issue, (as lately announced, from outsiders), I have, with some qualms, tack’d them on here,” he writes in

Collect’s

prefatory note. And yet the four poems, nine short stories, and a “Talk to an Art-Union” represented only a fraction of his early efforts; additionally, the works were often heavily revised to hide flaws of his early style.

Collect

(1882) entitled “Pieces in Early Youth, 1834-‘42.” “My serious wish were to have all those crude and boyish pieces quietly dropp’d in oblivion—but to avoid the annoyance of their surreptitious issue, (as lately announced, from outsiders), I have, with some qualms, tack’d them on here,” he writes in

Collect’s

prefatory note. And yet the four poems, nine short stories, and a “Talk to an Art-Union” represented only a fraction of his early efforts; additionally, the works were often heavily revised to hide flaws of his early style.

Twenty-three poems written by Whitman were published before 1855. The awkwardness of Whitman’s language and the conventional rhyme schemes and imagery will surprise anyone familiar with the energy and independence of his mature verse. Some of these pieces (like “The Death and Burial of McDonald Clarke” and “Young Grimes”) are directly imitative of popular poems of the time; others (“The Mississippi at Midnight”) are sensationalistic; still others (“Our Future Lot,” “The Punishment of Pride”) are didactic or overtly pious. One senses the insecurities of Whitman as man and artist: Trying so hard to please the average reader of New York’s penny-daily newspapers, he has forgotten himself and his own voice.

Yet there are signs of the great poetry to be written in the next decade. “Resurgemus” and “The House of Friends” indicate that Whitman’s political awareness was growing in the early 1850s; his interest in diverse peoples and cultures is exhibited in “The Spanish Lady” and “The Inca’s Daughter.” “Our Future Lot” and “The Love That Is Hereafter” are written on the themes of death and rebirth, key issues for his finest poems, including “The Sleepers” and “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking.”

For more examples of Whitman’s pre-1855 writings, see Thomas L. Brasher’s edition of

Early Poems and the Fiction

(see “For Further Reading”), Emory Holloway’s edition of

Uncollected Poetry and Prose of Walt Whitman,

and the two-volume edition of

The Journalism.

Whitman’s temperance novel, Franklin Evans (1842), is also available (New York: Random House, 1929).

POEMS EXCLUDED FROM THE “DEATH-BED” EDITION (1891-1892)Early Poems and the Fiction

(see “For Further Reading”), Emory Holloway’s edition of

Uncollected Poetry and Prose of Walt Whitman,

and the two-volume edition of

The Journalism.

Whitman’s temperance novel, Franklin Evans (1842), is also available (New York: Random House, 1929).

Readying the final edition of

Leaves of Grass

to be published in his lifetime, Whitman wrote in the “Author’s Note”:

Leaves of Grass

to be published in his lifetime, Whitman wrote in the “Author’s Note”:

As there are now several editions of L. of G., different texts and dates, I wish to say that I prefer and recommend this present one, complete, for future printing, if there should be any.

As a result of this announcement, the 1891-1892 edition has been considered the “definitive” or “complete” edition of his oeuvre.

There are several problems with the idea of considering the “Death-bed” Edition as “definitive.” For one, though the 1891-1892 edition contains Whitman’s greatest works, the style and sometimes the language of these poems reflects Whitman’s more controlled and conservative “late style” rather than the original energy and rawness of his message in the 1850s and 1860s. A quick comparison between the 1855 and 1891-1892 versions of “Song of Myself” is a case in point. In time, Whitman substituted the ellipses and irregular line lengths with more conventional punctuation and more even-tempered flow of language; he also removed blatantly provocative lines—“I hear the trained soprano.... she convulses me like the climax of my love-grip” on p. 57—with more demure observations—“I hear the train’d soprano (what work with hers is this?)” on p. 218. The “good gray poet” idea of Whitman is a lifetime away from the young rebel of 1855, and readers should be aware that the poetry reflects those changes in Whitman the man and poet. Knowing where he began and ended is a good way to gain a knowledge of the poet, but a stronger understanding comes from looking into his “stops” along the way—including the sexually charged 1860 edition, the strong patriotism of

Drum-Taps

(1865), the melancholy dreaminess of so many of the 1871 poems.

Drum-Taps

(1865), the melancholy dreaminess of so many of the 1871 poems.

BOOK: Leaves of Grass First and Death-Bed Editions

11.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Swimming at Night: A Novel by Clarke, Lucy

One True Thing by Anna Quindlen

Back to School with Betsy by Carolyn Haywood

Hammers in the Wind by Christian Warren Freed

The White Schooner by Antony Trew

Tahoe Blues by Lane, Aubree

Emancipating Alice by Ada Winder

The Following by Roger McDonald

Becoming Sister Wives: The Story of an Unconventional Marriage by Kody Brown, Meri Brown, Janelle Brown, Christine Brown, Robyn Brown