Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook (7 page)

Read Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook Online

Authors: St John Lauren

BOOK: Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook

13.88Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

‘Hi, Tariq,’ said Laura. Now that she was here, she couldn’t remember why she’d come. She’d wanted to get to know him, but that was assuming he wanted the same thing, which he might not. ‘Uh, umm, I thought I’d stop by and see how your hand was doing. Does it still hurt?’

He shook his head and held it out for her to see. He had a pianist’s fingers - long, slender and artistic. Laura was pleased to note that he’d changed the plaster on one of them and that the others were healing nicely. She’d left him the antiseptic lotion and box of plasters for that reason.

‘Dhannobad,’

he said, and she guessed that this time he did mean thank you.

he said, and she guessed that this time he did mean thank you.

She smiled. ‘You’re welcome.’

The door behind the counter opened and Tariq stepped rapidly away from her and shoved his hands in his pockets. He stared hard at the floor.

Mrs Mukhtar swept in, looking every inch a Bollywood star, albeit one who had spent a lot of time in the catering trailer. ‘Ah, Tariq,’ she said in a silvery tone, ‘I see you have found a friend. May one know your friend’s name?’

She directed the question at Laura, as if she didn’t expect her son to answer.

‘I’m Laura Marlin,’ Laura said, hoping she hadn’t got Tariq into trouble by distracting him from his work. ‘I just came in to buy a chocolate bar.’

Mrs Mukhtar’s laugh was like a wind-chime tinkling in the breeze. ‘Marlin? Isn’t that the great blue fish with the sword-like bill one often sees stuffed and mounted on hotel walls?’

Laura wondered what sort of hotels Mrs Mukhtar frequented, but she smiled and said yes. She’d never seen a shopkeeper’s wife who looked less like a shopkeeper’s wife, and was struck again by the difference between Tariq and his parents. It crossed her mind that he might be adopted.

Mrs Mukhtar smiled, revealing dazzling white teeth. ‘You must be the girl who gave First Aid to my son when he injured himself? Tariq told us all about you. My husband and I are in your debt. Tariq has the most beautiful hands and it is of the utmost importance that they are kept in good health. Isn’t that right, Tariq?’

She put an arm around Tariq and Laura saw a tremor go through his thin frame. ‘Now, if you young people would like to go for a walk on the beach or wherever, I am happy to mind the store for an hour until my husband returns.’

Tariq seemed startled. He spoke urgently to her in what Laura had learned from Mr Gillbert was probably Hindi, the official language of India. Mrs Mukhtar bowed her head like an athlete receiving a medal. ‘Oh, but I insist. The fresh air will do you good.’ She handed him an oversized coat. ‘Here. You can borrow this.’

As Laura and Tariq headed uncertainly for the door, Mrs Mukhtar called out in her silvery voice: ‘Wait, Laura. You have forgotten your chocolate bar. Now which one takes your fancy? Consider it a gift for your kindness to my son.’

There had been no boys at the Sylvan Meadows Children’s Home and the many schools Laura had attended had not equipped her for talking to a painfully shy boy who didn’t speak English. To hide her nervousness, she kept up a non-stop stream of chatter as they walked. They were on their way to the Island - not a real island but the green and rocky headland that formed the northernmost tip of St Ives.

Laura took Tariq on a roundabout route so she had an excuse to walk along Porthgwidden Beach, a tiny cove with creamy sand and big, spilling waves that sparkled in the late afternoon sunshine. He followed her down the steep steps reluctantly. Once on the beach, he stood stiffly with his hands in his pockets looking so uncomfortable that Laura wondered why he’d come. She supposed Mrs Mukhtar hadn’t given him much of a choice.

‘I’m guessing you don’t spend a lot of time on the beach,’ she said, taking off her shoes and padding barefoot across the shiny wet sand. ‘I dare you to come test the water with me. It’s freezing but it’s fun.’

He stayed where he was, staring at the ground. He looked utterly miserable.

The water was so cold it sent waves of pain shooting through Laura’s feet. She scampered back to the sand and wriggled her toes to get the blood flowing again. She was tempted to abandon the walk to the Island and forget trying to be friends with this silent boy who plainly would have preferred eating worms with Brussels sprouts to spending an hour with her, but she reminded herself that he was extremely shy and more accustomed to working. If Tariq didn’t know how to have fun, perhaps it was because he never got the chance.

On impulse, she pulled off her gloves, scooped up a double handful of icy water and splashed him. He was gazing into the distance and didn’t see it coming. The shock on his face was almost funny.

Laura immediately regretted what she’d done. She was stammering an apology when Tariq did something unexpected. He kicked off his shoes, ran to the water’s edge, and splashed Laura back.

She gasped at the coldness of it and burst out laughing. Rushing up to the breaking wave like a footballer taking a penalty, she kicked water in Tariq’s direction. He jumped out of the way, a big smile on his face, and sent another scoop of spray Laura’s way. Then he ran off down the beach. Up and down they chased each other, getting sandier and more drenched by the minute, until they collapsed on the sand, exhausted. They were laughing so hard their stomachs hurt.

Before the shadows could return to Tariq’s face, Laura said: ‘Come on, let’s walk to the Island.’

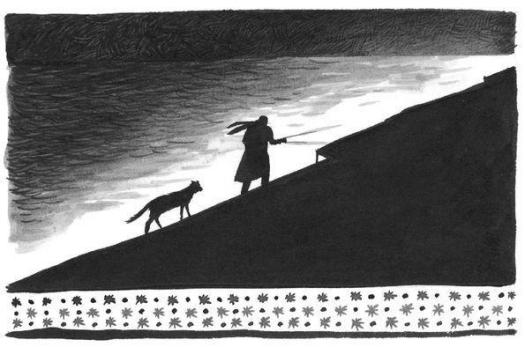

They climbed the hill to St Nicholas’s Chapel and sat on the ancient stone wall and stared out to sea. The wind cut like a knife and Laura, wrapped up snugly in a polo-necked jumper and warm coat, lent Tariq her scarf and gloves. The waves crashed and roared far below them. Laura pointed out her house, a speck in the far distance, and the route she took to school. She explained to Tariq how she’d come to live with her uncle, and told him about the mum and dad she’d never known.

He didn’t respond with words, but his mobile, expressive face showed she had his complete attention.

It was Laura who remembered the time. ‘Aren’t you supposed to be back at the store by now?’ she asked.

Tariq sprang off the wall as if it had suddenly become red hot. He handed her the scarf and gloves and gave a polite bow.

‘Dhannobad,’

he said sincerely, and then he was gone, streaking down the hill and along the beach road to the North Star Grocery.

‘Dhannobad,’

he said sincerely, and then he was gone, streaking down the hill and along the beach road to the North Star Grocery.

When Laura got home, she wrote down the word he’d used while she still remembered it. Not knowing the correct spelling, she wrote it the way Tariq had pronounced it:

‘Doonobad

- thank you’. She made up her mind to try to find a Hindi phrasebook or perhaps look up a few words on the Internet. If he couldn’t speak to her in her language, she would learn to speak to him in his.

‘Doonobad

- thank you’. She made up her mind to try to find a Hindi phrasebook or perhaps look up a few words on the Internet. If he couldn’t speak to her in her language, she would learn to speak to him in his.

7

‘DOES EVERYONE WHO

works for the fisheries work all hours of the day and night like you do?’ Laura asked her uncle. ‘I mean, is it a nice or a tough job, counting fish?’

works for the fisheries work all hours of the day and night like you do?’ Laura asked her uncle. ‘I mean, is it a nice or a tough job, counting fish?’

It was nine in the evening and Calvin Redfern had just come in from work. He’d missed dinner, but he’d cut two big slices of chocolate cake and he was making himself a black coffee and Laura a mug of hot milk. Lottie was gnawing on a bone in front of the stove.

‘A

nice

job?’ He looked at her in the intense, kindly way he sometimes did in the rare moments when his whole focus was on her. ‘Well, it’s not the world’s most glamorous job but I enjoy it. It pays the bills. Only trouble is, since my job is to check that fishing boats don’t catch more cod or haddock or other protected species than they’re supposed to, I have to keep the same hours fishermen do. Those hours are pretty unsocial, as you’ve gathered. Why do you ask?’

nice

job?’ He looked at her in the intense, kindly way he sometimes did in the rare moments when his whole focus was on her. ‘Well, it’s not the world’s most glamorous job but I enjoy it. It pays the bills. Only trouble is, since my job is to check that fishing boats don’t catch more cod or haddock or other protected species than they’re supposed to, I have to keep the same hours fishermen do. Those hours are pretty unsocial, as you’ve gathered. Why do you ask?’

Laura opened her school bag and took out her project folder. All she’d done so far was write the subject on the front.

‘My Dream Job.’ Her uncle laughed. ‘Come, Laura, you’re not going to tell me your dream job is counting fish?’

Laura flushed. ‘No, but the kids at school wouldn’t get it if I told them what I actually want to do.’

Her uncle glanced over his shoulder as he removed the pan from the Aga. ‘Is it a secret? Do you want to go to Hollywood, or become a brain surgeon or something?’

‘Not really.’ Laura suddenly felt shy. ‘I mean, it’s not really a secret. I could tell you if you like.’

Calvin poured foaming milk into a mug and handed it to her. ‘I’d like that very much.’ He went over to the coffee pot to fetch his own drink.

Laura, who’d never told her dream to anyone, said in a rush: ‘I want to become a great detective like Matt Walker.’

Her uncle’s mug smashed to the floor. Coffee sprayed everywhere. Lottie bounded up barking and Laura’s chair went flying as she leapt to escape the boiling black drops. Calvin Redfern’s face was a white mask. One knee of his trousers was black and steaming, but he didn’t seem to notice.

He said: ‘Well, that’s about the worst idea I’ve ever heard.’

Stung, Laura retorted: ‘It’s my dream and nobody’s going to stop me.’ She stood as far from him as she could without leaving the kitchen and tucked her hands into her pockets so he wouldn’t see them shaking.

Her uncle raked his fingers through his hair. ‘Laura,’ he said more gently, ‘Matt Walker is a character in a book. I enjoy reading about his adventures as much as you do, but do you really want his life? Do you really want to mix with the very worst people the planet has to offer? Do you want to get up every morning and come face to face with, or try to outwit, fraudsters, thieves, lowlifes and homicidal maniacs? Because that’s the reality, you know.’

Laura had asked herself the same question many times and she already knew the answer. ‘No. I don’t. But nor do I want evil criminals to get away with their crimes. I want to stop them. I want to help innocent people who don’t deserve to be hurt by them. I want to make the world a better place.’

Her voice trailed away. She’d never said these things to anyone and it was embarrassing to say them out loud.

Her uncle gave an odd, mirthless laugh. ‘No matter what people tell you, these things . . . these things . . . Oh, never mind.’

‘Never mind what?’ pressed Laura, but he bent down without explaining himself and began clearing up the broken china, carefully wiping the tiles and kitchen cupboards where coffee had splashed. When order was restored, he came over to Laura and stood looking down at her. His expression was rueful.

‘I’m sorry if my reaction scared you, Laura. You hit a nerve, that’s all. We’ve only known each other a short time but you’re already very precious to me. I want you to be assured that wherever you go and whatever you choose to do in life, you’ll have my unconditional support. I’ll do anything in my power to help you achieve your dreams and make you happy . . .

’

’

Laura pretended to be intently interested in the bottom of her mug. Her uncle had known her for less than a month and yet it never ceased to astonish her how much faith and trust he had in her. Considering how seldom he was around and that he’d never had children of his own, it was amazing how well he understood her. She was about to thank him, but it turned out he hadn’t finished speaking.

‘Except for this one thing. I can’t, and won’t, help you to become a detective. One day I’ll explain my reasons, but not today. Please don’t judge me too harshly until you know them.’

He smiled but his eyes were sad. ‘Now, if you’re not too mad at me or too tired, we could eat our chocolate cake, make fresh drinks and between us come up with a suitable job with which you can entertain your classmates.’

Other books

Naked by Eliza Redgold

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot

Seducing My Assistant by J. S. Cooper, Helen Cooper

All I Desire is Steven by James L. Craig

Heart of Iron by Ekaterina Sedia

The Great Railroad Revolution by Christian Wolmar

The Defiant One by Danelle Harmon

A Bookie's Odds by Ursula Renee