Laughter in Ancient Rome (20 page)

Read Laughter in Ancient Rome Online

Authors: Mary Beard

FIGURE 3.

Bronze statuette of an actor with an ape’s head (Roman date). This nicely symbolizes the overlap between the mimicry of actor and of monkey.

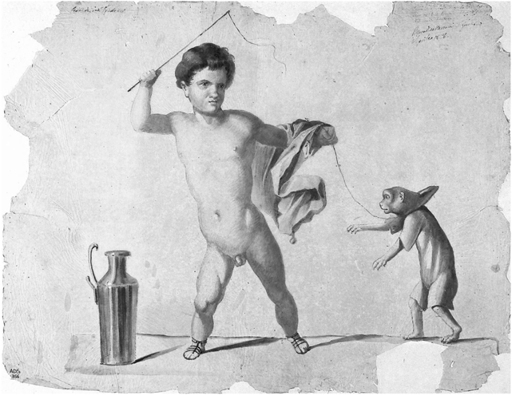

FIGURE 4.

A boy with a performing monkey, from an original painting (first century CE) in the House of the Dioscuri, Pompeii. The ape becomes an actor.

FIGURE 5.

Parody of Aeneas, escaping from Troy, with his father and son—with ape heads (from an original painting, first century CE, from Pompeii).

FIGURE 6.

Rembrandt’s self-portrait as Zeuxis (c. 1668). Notice the painting of the old lady in the background.

PART TWO

CHAPTER 5

The Orator

CICERO’S BEST JOKE?

Let’s start this chapter with a puzzle. In the middle of his long discussion of the proper role of laughter in oratory—in the sixth book of his training handbook for would-be public speakers—Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (or Quintilian, as I have been calling him) turns to discuss double entendres. “Although there are numerous areas from which jokes [

dicta ridicula,

literally “laughable sayings”] may be drawn, I must stress again that they are not all suitable for orators, especially those that rest on double entendre [

amphibolia

in his Latinized Greek].” He proceeds to quote a couple of puns that do not meet his high standards, even though uttered by Cicero himself. One is an abusive slur on the low birth of a candidate for political office, a fairly unsubtle play on two similar-sounding Latin words:

coquus

(cook) and

quoque

(also). The candidate in question was said to be the upwardly mobile son of a cook (

coquus

); when Cicero overheard the man canvassing for support, he is supposed to have gibed, “I will vote for you

too

(

quoque

).” This kind of joking is so beneath the elite orator, Quintilian explains, that he had thought of banning it entirely from the rhetorical repertoire. But he concedes that there is one absolutely splendid (

praeclarum

) example of the genre, which “on its own is sufficient to prevent us condemning this whole class of joke.”

1

That example also came from the mouth of Cicero, in the year 52 BCE, when he was defending Titus Annius Milo against the charge of murdering the radical and controversial politician Publius Clodius Pulcher. Cicero’s performance in this trial is usually regarded as unsuccessful, if not ignominious (a substantial majority of the jury convicted Milo of the crime). But Quintilian paints Cicero’s rhetorical role rather more honorably. Part of the case, he explains, hinged on timing, including the exact moment of Clodius’ death. So the prosecutor repeatedly pressed Cicero to say precisely when Clodius was killed. Cicero replied with a single word:

sero,

punning on its two senses, both “late” and “too late.” The point is that Clodius died late in the day—but also that he should have been got rid of years before.

2

It is not hard to see the joke here. The puzzle is why on earth Quintilian should have deemed it such an outstanding instance of a provocation to laughter that it rescued all jokes of this type from what would otherwise have been a complete ban. What was so especially good about this one?

The main focus of this chapter is laughter in Roman oratory and the chortles and chuckles of the Roman courtroom. What jokes were best at getting the audience to crack up? When should a speaker try to make his listeners laugh (and when not)? What were the pluses and minuses of using laughter to attack an opponent? Just how aggressive was public laughter in Rome? And what is the relationship between joking, laughter, and falsehood (or outright lying)? We shall meet virtuoso performers who raised a laugh by mimicking the posh voices of their adversaries, we shall come across some funny words that were surefire prompts to mirth (

stomachus

—that is “stomach”—was apparently one that was always likely to get a Roman going), and we shall glimpse a hilarious competition in making pig noises between a peasant and a professional jokester. I also hope that by the end of the chapter, we may have a better idea of why that particular quip on the time of Clodius’ death attracted Quintilian’s fulsome praise.

CICERO AND LAUGHTER

My leading character throughout the chapter is, of course, the most infamous funster, punster, and jokester of classical antiquity: Marcus Tullius Cicero. It is true that Cicero now, even among many scholars, has more of a reputation for humorless pomposity than for engaging wit. “Cicero can be a fearful bore,” as one of his best twentieth-century biographers wrote (perhaps saying rather more about herself than about him), and more recently another senior classicist (jokingly) dismissed him as the kind of man who would have been no fun at all as a dinner companion.

3

But in antiquity, both in his lifetime and as he was reinvented over the centuries that followed, one of Cicero’s trademarks, for better or worse, was his capacity to get people laughing—or his sometimes irritating inability to refrain from doing so.

4

This is a major theme in Plutarch’s biography, written some 150 years after Cicero’s death. From the very first chapter (where Plutarch repeats a joke that Cicero made on his own name, which means “chickpea” in Latin), the

Life

returns again and again to the theme of the famous orator’s use of laughter: sometimes to his witty bons mots, sometimes to his ill-advised tendency to crack a gag in very inappropriate places. Plutarch admits that Cicero’s exaggerated sense of his own importance was one of the reasons for his unpopularity in some quarters, but he also attracted hatred because he attacked people indiscriminately, “just to raise a laugh,” and Plutarch quotes a variety of his gibes and puns—against a man with ugly daughters, against the son of a murderous dictator, and against a drunken censor (“I’m afraid the man will punish me—for drinking water”).

5

One of the most notorious occasions of Cicero’s ostentatious use of laughter was during the final civil war of the Republic—between Julius Caesar and Pompey—which was the prelude to Caesar’s autocratic rule. After much hesitation, Cicero joined Pompey’s camp in Greece in the summer of 49 BCE before the battle of Pharsalus, but he was not, says Plutarch, a popular member of the squad. “It was his own fault, as he did not deny that he regretted having come . . . and he did not hold back from joking or making witty gibes at his comrades; in fact, he himself was always going about the camp without a laugh, and frowning, but he made others laugh, quite against their will.” (“So why not employ him as guardian of your children?” he is said to have quipped, for example, at Domitius Ahenobarbus, who was promoting a decidedly unmilitary type to a command position on the grounds that he was “mild-mannered and sensible.”)

6

Several years later, after Caesar’s assassination, Cicero replied to some of these criticisms in a pamphlet now known as the second

Philippic,

a vicious attack on Mark Antony—who, among other things, had clearly leveled, or repeated, some of the charges of inappropriate jocularity.

7

Like Plutarch, Antony had most likely objected to Cicero’s habit of making his comrades laugh in such awful circumstances, and against their will (effectively an assertion of his control over their “uncontrollable” outbursts of laughter). In a characteristic rhetorical sweep, Cicero at first brushes the accusation aside: “I’m not even going to respond about those jokes you said I made in the camp.” But then he does offer a brief defense: “To be sure, that camp was full of gloom, I admit. But all the same, even if they are in dire straits, men do still take some relaxation from time to time; it’s only human. Yet the fact that the same man [Antony] finds fault both with my melancholy and with my jesting is a powerful proof that I took a moderate line in both respects.”

8

Cicero justifies laughter as a natural human reaction even in troubled times while also pleading moderation in his conduct.

9

It is, however, in his comparison of Cicero and the Greek orator Demosthenes, which forms the postscript to this pair of parallel lives, that Plutarch offers his most pointed comments on Cicero’s use of laughter. These were the two greatest orators of the Greco-Roman world (hence their treatment as a pair), but their use of laughter was starkly different. Demosthenes was no joker, but intense and serious, even—some would say—morose and sullen. Cicero, on the other hand, was not only “addicted to laughter” (or perhaps “quite at home with laughter,”

oikeios gelōtos

); he was, in fact, “often carried away by his joking to the point of buffoonery [

pros to bōmolochon

], and when, to get his own way in the cases he was pleading, he handled matters that deserved gravity with irony, laughter, and mirth, he neglected decorum.”

10

Plutarch quotes a telling Roman quip about Cicero’s jocularity. During his consulship, in 63 BCE, he was defending Lucius Licinius Murena against charges of bribery, and in the course of his defense speech (a version of which still survives), he made tremendous fun of some of the absurdities of Stoicism—the philosophical system vociferously espoused by Marcus Porcius Cato, one of the prosecutors. When “clear laughter” (the Greek word is

lampros,

literally “bright”) spread from the audience to the judges, Cato, “beaming” (

diameidiasas

), simply said, “What a

geloios

we have for a consul.”

11

The Greek word

geloios

has been translated into English in several different ways: “What a

funny

consul we have!” “What a

comedian

we have for a consul.”

12

But what did Cato say in his original Latin? One possibility is that he called Cicero a

ridiculus consul.

If so, it will have been a nice joke, because

ridiculus

—one of the most basic terms of Latin laughter vocabulary—was a dangerously ambiguous word. For, in a way that constantly destabilized Roman discussions of laughter,

ridiculus

meant “laugh-able” or “prompting laughter” in two ways: on the one hand, it could refer to something that people laughed at, the butt of laughter (more or less “ridiculous” in the modern sense); on the other hand, it was someone or something that provoked people to laugh (and so it could imply something like “witty” or “amusing”). As we shall find in what follows, this was a pressing ambiguity in Roman culture, exploited and debated in various ways. Here, if Cato really did say that Cicero was a

ridiculus

consul, he was cleverly pointing the finger at his rival, insinuating that such a smart jokester was also a man that the audience should laugh

at.