Las Christmas (18 page)

Rosario Morales

Rosario Morales was born to Puerto Rican parents in New York City. She grew up

in Manhattan and the Bronx and moved “back” to Puerto Rico when she was

twenty-one. She writes fiction, memoir, and poetry in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies such

as

This Bridge Called My Back, An Ear to the Ground,

and, most recently,

El Coro: A Chorus of Latino and Latina Poets.

She coauthored

Getting Home Alive

(Firebrand)

with her daughter, Aurora Levins Morales.

I DIDN'T GO HOME (CHRISTMAS 1941)

I HEARD THE ruckus in the hall outside the door to the children's ward, the nurses arguing in their soft, annoyed voices, his voice deep and determined. I knew he was coming to take me home even though I didn't have to leave until the next day. It wasn't even visiting hours. It was Sunday morning. The sun streamed in the windows at the long side of the ward. The bustle of the morning had just died. No more toothbrushing. No more injections or pills. No clatter of dishes and spoons. No embarrassing ordeal of doing it on a pot by the side of the bed. Now I was savoring the calm, lying quietly in the sun, and watching the baby in the glass-enclosed room at the end of the ward laughing at the faces that the little girl with leukemia was making at the poor thing. Soon the lady in the pink-striped apron would come with toys and puzzles, with books and cards. I wondered what we'd have for lunch.

My father gave me an awkward hug, kissed my cheek, and said,

“Ven,

m'hijita. Vente, nos vamos,”

while I lay back on the bed not going, not putting on the blue-flowered dress he pulled out of the grocery bag he was carrying. I looked at him trying to say no and not knowing how. I hadn't had too much practice. I especially didn't like to say no when he was so pleased, so sure he was giving me a treat. He was taking me home for Christmas, away from the hospital where I was lonely and afraid. But I wasn't lonely and afraid. Not even when they wheeled me into the operating room with my eyes wide open staring at the tiled walls, the blinding light, the tanks of gas, the white uniformed people, the awful black mask that cut off all air. “Breathe in,” they said when I held my breath to keep the sweet strong stuff from entering my lungs. “Breathe!” Good obedient child that I was, I did, and heard their voices disappear into a dream.

Here in the ward I had more company than anywhere but school. All the grown-ups were polite, and while they never hugged me or kissed me or called me “

nena

buena

” or “

nena

linda

” they never hit or yelled at me or at each other. I did get scolded for laughing at the kid in the next bed straining on the pot, and when my turn came to strain and cry from the pain, I was laughed at, too. But even so, I didn't want to be cheated out of the twenty-four hours I had left.

Papi looked at my face, worrying.

“¿Qué pasa? ¿Te duele algo?”

“No, Papi. I don't hurt.” “Come, then,” he said, switching to English, the kind of English I still like, the sharp edges softened by his Spanish accent. “Get dressed and we'll go home and have some

asopao.

” But not even

asopao

could make me go home of my own free will. Mami would cook

asopao

again but I would never have appendicitis again, not ever. I didn't have an appendix anymore. This was the last day I could lie here in the morning. The last day I would translate for the doctor who came around at noon and didn't understand what the patient with kidney stones in the next ward was saying. I understood her. I spoke both her language and his. It was my last day to nap with ten other children. The very last day I would get up and play with the dollhouse that I had decorated with mirror ponds and cotton-ball snow.

I said something to Papi in a low voice, I can't remember what. But when he leaned down to hear better, I remembered the treat in store that Sunday and whispered that the lady from the agency was bringing Christmas gifts to all the children in the wards today, this very afternoon. I turned my head, ashamed. He'd argued so hard with the nurses, worked so hard to get me home early, rules or no rules. But I didn't get up, I didn't back down, and I didn't go home. So when the head nurse came to see me off I was lying with my head turned to the wall, tears sliding down my cheek, my father standing over me, holding my socks and panties in his big, still hands.

Puerto Rican Asopao

In Esmeralda Santiago's family,

asopao

is often the meal after the meal. Her mother, Ramona Santiago, usually makes this soup after everything else has been eaten, the Christmas dishes have been washed, and leftovers have been divided and stored in plastic so that everyone can take a bit of the Christmas meal home. As guests begin to leave the party, Mami offers the

asopao

. This happens every time the family gathers, not just during Navidades, but it's at Christmas when it's most appreciated, as we prepare to battle the cold and snow of life away from Puerto Rico.

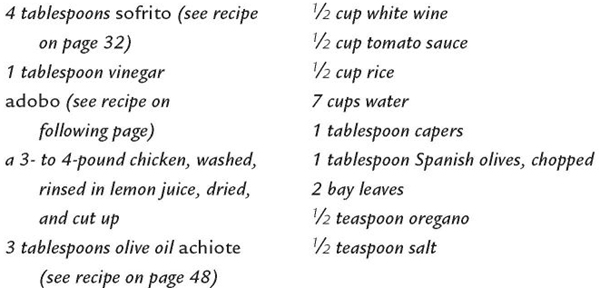

Add 1 tablespoon of the

sofrito

with the vinegar to the

adobo

mixture in a bowl and blend well. Rub the mixture over the chicken pieces. Let marinate in the refrigerator for at least 30 minutes, preferably overnight.

In a soup pot, heat the olive oil

achiote.

Add remaining 3 tablespoons

sofrito.

Cook for 2 minutes.

Add chicken. Cook over medium heat, stirring frequently to ensure that all the pieces of chicken are seasoned. Continue cooking a few minutes more until the chicken is opaque.

Add the white wine and tomato sauce and stir well, then add the rice, water, capers, olives, bay leaves, oregano, and salt. Return the mixture to a boil, then lower heat and simmer, covered, 20 to 25 minutes. Add salt and pepper to taste.

Makes

6

to

8

servings

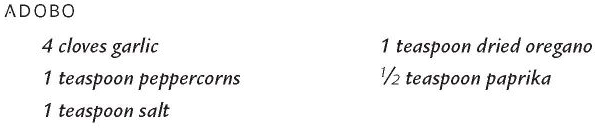

Grind all the ingredients together in a mortar and pestle to make a paste.

MartÃn Espada

MartÃn Espada was born in Brooklyn, New York. A recipient of fellowships from

the National Endowment for the Arts and the Massachusetts Cultural Council,

he is currently Associate Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts,

Amherst. His collections of poetry include

Imagine the Angels of Bread (W. W. Norton),

which won the American Book Award

; and Rebellion Is the Circle of a Lover's Hands

(Curbstone Press), which was awarded both the

Paterson Poetry Prize and the PEN/Revson Fellowship. He is the editor of

Poetry Like Bread: Poets of the Political Imagination from Curbstone Press

and

El Coro: A Chorus of Latino and Latina Poetry.

His poetry has

appeared in the

New York Times Book Review, Harper's, The Nation,

and

Ploughshares.

ARGUE NOT CONCERNING GOD

I WAS RAISED by a Puerto Rican father and a JewishâJehovah's Witness mother. They met while working at the same factory in Brooklyn; my father was a shipping clerk, my mother a receptionist. Frank Espada was a skeptical and wayward Catholic. Marilyn Levine ate cheeseburgers and expected to be bug-zapped by God for mixing meat and milk in violation of dietary laws.

There is a context for her repudiation of the Jewish faith and identity in favor of a relentlessly proselytizing door-to-door Christian sect most people find more irritating than a case of ringworm. Sometime between her marriage to my father, in 1952, and my arrival, in 1957, my mother's family disowned her. At age two I glimpsed my mother's father, who escaped from a nursing home. In forty years, this is the only time I can remember meeting anyone on her side of the family, so complete was our ostracism.

Boxed into the Linden projects of East New York with three children in the early 1960s, my mother heeded a stranger at the door selling magazines and prophecy. During my father's regular absences, my siblings and I became, in effect, Witnesses as well. We learned that the Witnesses predicted “the end of this system of things,” or Armageddon, a reference to the apocalypse, characterized in the magazines by pictures of crowds shrieking and cowering under a hail of fire. However, the Witnesses always chirped about “the good news” whenever they forecast the tongue-rotting demise of the damned (i.e., anyone not a Jehovah's Witness). After Armageddon came Paradise, like dessert.

Illustrations of Paradise featured somnambulant beneficiaries of eternal life petting equally stupefied lions: Jehovah as taxidermist. The gardens were sterile, the faces numb with narcotic smiles. The Witnesses equated perfection with the deliberately bland, even when they sang. At an early age, I was convinced that their hymns were based on theme songs from television shows. Their aversion to any exuberant or celebratory worship, their awkward austerity, also explained why the Witnesses did not observe Christmas. Of course, millions of people in the United States have no need for this particular holiday; but Christmas, or the lack thereof, became a metaphor for my family's contradictions and illusions.

We celebrated Christmas when I was very young. I can recall swatting my brother into the Christmas tree, which collapsed with the explosion of ornamental bulbs, a detonation of holiday grenades. My parents discovered me untangling my brother, and a great bellowing ensued. (I have learned since that other families also use their Christmas trees as projectiles. My father-in-law once heaved his Christmas tree like a harpoon through a picture window.)

Some time thereafter, my mother announced that she would no longer observe Christmas. She took the official Witness position that Jesus was not actually born on December 25. This was an ancient Roman holidayâa pagan holiday. My father ruled in turn that, if my mother wouldn't celebrate Christmas, then nobody would. This was a family holiday, and if my mother wouldn't celebrate Christmas, then we wouldn't celebrate Christmas

together,

like a family.

However, my father kept his lifelong collection of Christmas ornaments, presumably hoping that my mother would change her mind. My mother made her state of mind very clear one December, a few days before Christmas, during my adolescence. She gathered my father's Christmas ornaments, dropped them in a garbage can, dragged the can to the corner, waited for the trash man to jingle the garbage into his truck, then returned to the house and declared to my father that she had thrown out his treasures.

She did it on his birthday. The Witnesses do not celebrate birthdays, either. This is considered self-exaltation, idol worship. For one day, you are the Golden Calf. Besides, the only two people to have birthday celebrations in the Bible are Pharaoh and Herod. Following this logic, a few balloons and conical party hats may lead the birthday boy or girl to conquer vast deserts and dragoon thousands of slaves to build pyramids.

Thus my mother tossed

Feliz Navidad

into a trash compactor. The argument that followed combined the best features of a theological debate and a cockfight: God, Darwin, screeching, and feathers. I cannot recall my father's words. First his jaw trembled, which was always the prelude to a seismic event. Then the eruption began, his mouth open so wide I swore that I could see his uvula, that tiny punching bag, as if he were a cartoon opera singer.

One of my mother's most frequent quotations from the Bible comes to mind: Jesus said, “I came to put, not peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). Jehovah's Witnesses would cite this verse to justify the breakup of families. Of course, this is the Witnesses' own “New World” translation of the Holy Scriptures. Considering the intricacies of translations from an ancient language, Jesus might well have said, “I came to poach a naughty piece of swordfish.”

After my mother's Garbage Offensive, there was no talk of Christmas. My father bought me a duffel bag one year. He told me: “Hey, I'm buying you a duffel bag.” To which I replied: “I don't want a duffel bag.” He responded: “You're getting a duffel bag.” And he gave me a duffel bag, unwrapped, so I would know that it was a duffel bag. Oddly enough, I was not planning on going anywhere.

In high school, I became a Christmas anarchist. I explained the fact that my family didn't celebrate Christmas in revolutionary terms. Christmas was a manifestation of corrupt consumer culture, a capitalist conspiracy, a hypocritical ceremony of the warmongering state. Some of which is no doubt true, though what mattered was the marriage of convenient logic and high sanctimony. I was feeling very spiritual.

But I did not need the Witnesses anymore. My father's arguments for agnosticism and evolutionary theory were ultimately persuasive. My mother's only response to the theory of evolution was, “You may be descended from an ape, but I'm not.” My mother's credibility also suffered when the Witnesses predicted “the end” for October 1975, and nothing ended but the baseball season. Moreover, in high school I had discovered girls. One cherubic creature from the local congregation left me with the demeanor of a cow brained by a sledgehammer. I became enamored of this particular headache, and since the Witnesses dictated a code of sexual behavior only a Ken doll could obey, my choices were crystallized.

This is an account of redemption, however. My Christmas history was redeemed by pork:

pernil

in steaming chunks, with slivers of garlic, and

cuero,

the skin that cracked in my squeaking teeth. Every Christmas season during our Brooklyn years, we would travel to the Bronx for dinner at my grandmother's apartment. I was buttoned into my blue suit, a diminutive pallbearer. I then drifted in a Dramamine twilight as the car lumbered through traffic. The only mention of God was my father's litany of “Goddammit! Goddammit!” as we inched down the oxymoronic freeway. Once we arrived in the Bronx, my father would load me with presents for my cousins, and I reeled up five flights of tenement stairs. The door opened on what must have been thousands of Puerto Ricans, all related to me, and the slow dizzy bolero on the record player that left me swaying like a buoy at high tide.

Then came my grandmother's

pernil

with

arroz con gandules.

A boy of generous girth is apt to believe that divinity is a plate of roast pork with rice and pigeon peas. This was the celestial feast. Mysteriously, my grandmother never ate. No one ever saw Tata chew or swallow anything. That was further evidence of the miraculous, a virtual weeping statue in the town plaza.

After dinner my father would organize the family photograph, a gallery of faces with the broad Roig nose, my grandmother's nose and mine, a hill with two caves. My mother posed with the pagan Puerto Ricans, forgetting for the moment that Christmas was not the birthday of Jesus, ignoring the omnipresent plaster saints of the Bronx, simply because the pagans insisted on waving her into their snapshots.

My mother is still a Jehovah's Witness. Unlike me, my young son has never heard a debate over whether

his

father is descended from an ape. My wife, born on a Connecticut dairy farm, crafts ornaments by hand and saws down her own Christmas tree in the woods. We celebrate Hanukkah and the DÃa de Reyes too. Expensive, true, but this year I am planning to moonlight as a professional wrestler to bring in some holiday cashâring name El Pernil.

I leave the final word to that great Puerto Rican poet, Walt Whitman, from the 1855 introduction to

Leaves of Grass:

“This is what you shall do: Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God . . .”