Lark and Termite (19 page)

Authors: Jayne Anne Phillips

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #History, #Historical, #Fiction - General, #War & Military, #Military, #Family Life, #Domestic fiction, #West Virginia, #1950-1953, #Nineteen fifties, #Korean War, #Korean War; 1950-1953

July 28

Winfield, West Virginia

JULY 28, 1959

Lark

Rain falling across the alley and the backyards looks green as grass against washed brush and soaked trees. You see through it like it might rain forever, and you forget how hard it’s pouring until you stand out in it. Nonie said the rain drummed all night, and she went to work early in case they have any water to mop up at the restaurant. The backyard looks thick and spongy. Dimpled water stands in the tracks of the alley, and I’m staring out the screen door, feeling the rush of breath falling water makes. Termite likes the sound and he likes it if I shut the back door, open it, shut it again, like I’m changing the weather in the room. I shut the door and think about the water coming up, how it’s moving up the slant in the basement floor. I butter the toast, and when I turn to open the door again Solly is there, up close in a dull black slicker, water running off his face in the billed hood.

“Lark, you OK?” He’s nearly shouting in the sluice of the water. “My dad said to drop off these water jugs. He said to fill them while the tap still works, in case the power goes off.”

I move to let him in and the hood falls back off his wet hair. I realize I haven’t seen him close since before I left school, since I’d pass him in the halls and he’d look at me, some girl or other trailing after him. It got around that we were cousins, to explain the looks between us and the growing up together, our houses like two shambling arms of the same building, except Solly’s is bigger. Cousins because people think of Nonie and Nick Tucci as weirdly related, both alone with kids living off the alley, like we’re all a tribe down here, not quite across the tracks but almost. And we’ve got these missing persons, like old mysteries.

“You want some toast?” I ask Solly.

He looks at the hot bread in my hands, and then he’s at the sink with the plastic jugs. “No thanks,” he says.

He steps out of his boots and I see the shine of blond whiskers along his jaw, on his cheeks that look hollowed out. He’s got such long bones, Solly does, and a bruisy mouth, like his lips are a little swollen. Most people wouldn’t say he’s handsome. His face is too mismatched, the square chin and straight nose, the deep-set eyes. He stands there dripping on the linoleum by the shelves of cans and bottles, filling the plastic jugs and capping them, and a steam nearly rises off him. The rain is cool and warm at once. “Seems strange to put water by with so much of it pouring down,” I tell him.

“Yeah, well, if you end up on the roof you could catch it in your hands and drink it. May not come to that, but the river is rising fast. They don’t expect the crest until tonight. Lumber Street will flood for sure and they’ve closed the bridge. Nonie go to work today?”

“Sure. She and Charlie? You kidding? They’d go to work unless the town closed down.”

“It just might. Lark, the Armory is open. They’ve got food, cots, a generator. I could take you and Termite there now, just in case. No need for boats.”

“He’d like a boat ride.” I smile, but Solly doesn’t. I fold Termite’s toast in a four-square and put it in his hand. That way he can hold it himself. “Solly, you know the Armory will scare him, all those people, all that noise. We need to stay here unless we really have to leave. Even if Nonie can’t get home tonight, I can manage.”

“How will you manage?”

“We have a bed in the attic, and room for groceries and blankets and water. I’ve stacked up some of the furniture down here. Maybe you can help me get some things upstairs. The rest will have to fend for itself.” I’m standing behind Termite’s chair, and I look over at Solly. It feels hard to walk over near him, cross a few squares of linoleum flooring, but I do. We stand at the kitchen window, inches apart, nearest the pour of the rain. “If it gets bad enough, you’ll come and get us.”

“Yeah,” he says, “I will.” He’s not going to argue. He looks at me with that mix of hard and soft in his eyes, and he won’t look away.

I open the refrigerator and reach into it like there’s something I need. “We’ll be fine,” I say.

There’s a silence, like he’s waiting for me. “All right, Lark.”

Termite is still. I can feel him, tuned in to us, to the spaces between our words, and I rattle the loose metal shelf in the fridge, shift jars and milk bottles, before I shut the big door.

Solly is moving the water jugs, lining them up beside the wall. “You’ve got plenty of bottled water now, anyway,” he says. Then he moves past me and crouches by Termite’s chair. “Hey Termite,” he says, “you like rain? It’s raining. No wagon today.” He puts his hand on Termite’s shoulder. “That wagon would fill up and float,” he says softly, then he looks up at me. “He used to talk to me. He doesn’t answer me anymore. I know he knows me.”

“Of course he does. Just not so used to you as he was.”

“Yeah. That wagon. I see you pulling him in it, up the alley. He still likes it. A couple more years though, he won’t even fit. He still like the radio? Termite, I know a station you might like. Jazz, with voices but no words.” Solly pulls the radio toward Termite across the kitchen table, but Termite looks away. And I know he won’t eat. It’s too different that Solly’s here. I’ll have to make him food later.

“He’ll listen another time,” I tell Solly. “It’s just, he’s listening to the rain. Like he thinks he can hear when the sound of it is going to change.”

“Change? He’s a weatherman now? Maybe he could stop it raining. Someday it’ll stop. Things do stop.” Solly stands. “You need me to go to the store for you? Anything like that?”

“We’ve got plenty of food from the restaurant. But there’s water coming up in the basement. I wonder if you could help me move some boxes. I don’t want to ask Nonie, and I can’t lift them by myself.”

“Lights working down there?”

“By the workbench. But I’ll get a flashlight.”

I get into the drawer for the flashlight and I feel Termite start to nod and rock in his chair, like he does if there’s a new hum of energy, anything strung out.

“Yeah, Termite, it’s me.” Solly touches Termite’s back, a man’s touch, quiet and still, and Termite stops.

I turn away from them and start down the basement steps. “Termite is all right up there,” I call back. “He’ll let me know if he gets bored.” I hear Solly on the stairs behind me in his boots and I feel a shudder inside, like he’s come back and we’re both much smaller, together all day like we used to be. I pull the chain over the workbench and the light goes on over words we carved in the wood, our names, a little family of stick figures, and the requisite bad words,

s-

words and

f-

words. We wrote prayer words too. We wrote “Jesus.” Angled into a corner, small, like a flower almost, is Joey’s faint drawing of a cock.

Solly runs his hand over the scarred wood, over Joey’s little hieroglyph. “Joey,” he says. “Always such a father figure, wasn’t he.”

I shine the light where the dark is darker, and I hear the slip of water. I see it’s higher than it was two hours ago. “There are eight boxes,” I tell Solly. “Big ones, stacked up.”

“She used to have a bedspread over these,” Solly says.

“How do you know?”

“I remember a big shape in the corner, and the cloth of the spread was red checks. Don’t you remember? We bounced balls against it. We climbed on it.” He looks at me, unsmiling. “What is it with you? Holes in your head?”

“I never paid much attention, I guess. But there’s no cloth now, and I’ve been home with Termite, and I noticed the boxes, the return addresses. Florida. I opened one, and I think they came from my mother. I can’t imagine why else Noreen would be keeping them.”

“You ask her?”

“I’m not ready to ask. I want to go through them.”

“For clues.”

“Maybe.”

Now he smiles. “Don’t you ever think our mothers might be drifting around a swimming pool together on one of those blow-up floats, sipping cool drinks under palm trees?”

“They didn’t know one another, did they?”

“No, they didn’t, but it doesn’t seem like that, does it? My dad, he knew them both, and they both left, and left their kids. Remember that next time Nick gives you the eye.”

“You think it was all about Nick?” I smile, to show him it’s a joke.

“No. He’s just another link between them. But doesn’t it seem sometimes like they were sisters under the skin, or maybe even the same person?” He pulls the slicker hood off, unzips the front of the jacket. “After she was gone awhile, I started pretending that. It made you and me more the same.”

He looks at me so hard I step back. But he’s already grabbed me, without ever moving. It’s because of the room. Now I remember the red-checked cloth, with lawn chairs leaning up against it, and a couple of old cot mattresses thrown over the top. Nonie kept the storm-cellar doors open in the summer, and we came in and out that way, under the branches of bushy lilacs that hung over both sides. They’re gone now. “You think you need me to help you with those boxes?” I ask him. “They’re pretty heavy.”

“I think I can manage, Lark,” he says, with an edge. “You want them in the attic?”

“It’s the only second floor we’ve got.”

“Don’t worry. The water won’t get that high unless most of the town floods. Which might not be a bad idea. We could all float away.”

I hear the bell on Termite’s chair. He rings it once. “He wants something. I’ll go up.”

“Yeah, go on up with him.” Solly pulls off the slicker and he’s wearing a flannel shirt with the arms cut out. His arms are tight. For so many years, even though he was a year older, he was my size. I’m always surprised at how tall he is, muscular and lean, like I turned around and he changed. He does all the sports with the dumb jocks and he gets what the dumb jocks get—the blond girls with their flipped hair and a job at the gas station the summer after graduation. I suppose now he pretends he’s like those girls, with their sweater sets and college funds, like he lives in that secondhand convertible of Joey’s that he keeps so clean, driving girls here and there. Probably a good plan. Even if their Mommies and Daddies figure it’s high school stuff. They’ll ship their girls off now, get them away from Saul Tucci. Solly is not what they want.

“You going off to school, Solly?” I can’t help asking him.

“Like the rest of the sheep? Go play some football fifty miles from here? Nah, I don’t think so. There was one letter I answered—Fort Lauderdale. Lure of the sea. My own palm tree.” He rakes his fingers through his wet hair and I see the darkish roots at his hairline. One of those girls bleached his hair like hers, playing at twosies. My twin. He looks straight across at me. “Shot in the dark. We’re only a double A team. Wasn’t like I had endless offers.”

Solly in Florida, I think. Solly in Florida.

“Don’t know about that one yet,” he says. “I haven’t told Nick about it, or anyone.”

“Well. Let me know, when you hear.”

“Yeah?”

I want to get away from him. “Sorry it’s so close down here. Gets hot, with the windows shut against the rain.” I turn and start up the stairs and he stands there like he’s watching me walk out of a story. For a weird moment I think I hear his heart beating, but it’s my own head pounding, a thud I only notice when I get up the steps and back into the kitchen. Things stop, Solly said. I think about living here on and on, and he wouldn’t. I think about going away myself, living a whole different life, like I could exist on a different planet and this life wouldn’t know about me, and I wouldn’t know about it. I sit down in a kitchen chair close beside Termite and I see his toast on the table where he dropped it. “You hungry yet?” I ask him, but my voice has a dead, automatic sound, and he puts his arms across my knees. He smells of the baby powder Nonie and I still dust across his shoulders after baths. I realize I’m never going to leave him, not in this life. He’s so quiet, listening. His open hands in my lap barely move, so faintly, like his thin fingers touch a current of air I’m too thick and gross to feel. The undersides of his fingers are white as alabaster, unlined between the knuckles, like he’s always just born. There’s a faint pink blush under his skin. When he has a fever, his skin gets dappled.

We hear Solly coming up the stairs with the boxes. I feel him look in at us. He turns in the little hallway, walks into Termite’s room and on into the attic, up the pull-down steps in Termite’s ceiling. Termite hears Solly in his room. He likes the attic steps, the creak they make pulling down, how they sound under someone’s weight. It’s like the air in the attic falls down those stairs in moted streaks cast through the dormer window above. Termite can smell it and feel it, but he doesn’t stir now.

“I want you to have a real breakfast,” I tell him. “I’ll make you and Solly something.” He lets me talk.

I peel some peaches and start the toast again. All the time I’m cooking the eggs, Termite touches one wrist to the radio, but he leans away when I move to turn it on. I get the food on the plates and I hear Solly, up and down the basement steps. Then he’s in the kitchen.

“I lined up the boxes along the wall by the attic window,” he says. “You’ll have enough light to sift through the evidence. May as well leave them up there. Safer. Nonie’s basement takes in water, any big rain.”

“Thanks, Solly. I made you some food.” I’m washing the cast-iron skillet in the sink and Solly comes over near me and puts his hands on me, up under my hair, on my neck, just for a second, as though to move me aside. He’s taken his shirt off and tied it around his waist, and he leans in to splash his face in the stream of water.

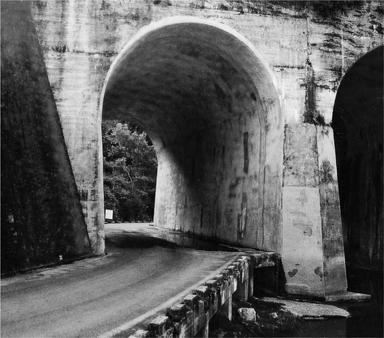

“Those boxes were dirty,” he says. “I kept wondering why. Like mud splashed up on them. Then I realized the backs were covered with crumbled hornets’ nests. Old ones. Muddy dust.” He unties the shirt and wipes his face with it. Then he sits down by Termite, puts the spoon in Termite’s hand, starts helping him. The water is running, but I can hear Solly talking. “We used to go down by the rail yard, Lark and me and you, or down under the railroad bridge by the river, and we’d take bottles of soda pop and those cans of ravioli Joey heated up for Tucci dinners when the old man wasn’t home. I’d feed you and we’d wait for trains. Bet you don’t know that. Bet you don’t know that anymore.”