Lamplighter (19 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

“Yes, very good.” The Lady Vey looked over her shoulder and gazed around slowly. She saw her daughter immediately, as if she knew where she was all along. Something profound and complex transmitted between mother and daughter, something beyond Rossamünd’s comprehension. For all her tough talk and showing away, Threnody seemed to flinch, and hung her head in uncharacteristic defeat. The Lady Vey swept up the manse steps, unheeding of the bureaucrats and the attendants all deferring a pace to give her room as she slid past.

Threnody rolled her eyes, bravado quickly returning. “Off to my executioners,” she said with ill-feigned indifference.

Rossamünd frowned and blinked. “Pardon?”

“My mother is

never

happy with me,” she sighed. “And I go to find out just how unhappy she is . . .”

never

happy with me,” she sighed. “And I go to find out just how unhappy she is . . .”

“Oh.”

Hardening her face and hiding her dismay, Threnody obeyed some invisible command and left to join the new arrivals.

Left alone as the day-trippers left for Silvernook, Rossamünd went his reluctant way to the kitchens.

Mother Snooks did not want to see him. Looking haggard, she dismissed the young prentice from her sight almost as soon as he entered. “Be on ye way! Whatever wicked crimes ye have to serve yer wretched day atonin’ for, it won’t be done here. Go!”

Knowing full well that Grindrod had just departed on a south-bound lentum, Rossamünd was puzzled as to what to do next. It was tempting to exploit this as a twist of fortune and take an easy day after all. However, if he did not serve one imposition now, he would only have to serve two later. Knocking at the sergeants’ mess door, he asked Under-Sergeant Benedict instead.

“Well, Master Bookchild,” the under-sergeant said, stroking his chin, “we must find you another task, else our kindly lamplighter-sergeant might set you more. If the Snooks won’t have you, then perhaps Old Numps will.”

“Who?” Rossamünd asked.

“He’s a glimner working down in the Low Gutter.You’ll find him in the lantern store, Door 143, cleaning lantern-panes. You can clean them with him—a nice simple task for a vigil-day imposition.”

Rossamünd felt anxious. He had heard of the mad glimner in the Low Gutter. It was the same fellow Smellgrove had been telling of at Wellnigh.

“Be on your way, lad,” Benedict instructed, “and work with Numps till middens. I’ll report to Grindrod that your duty—we’ll call it panel detail—was served. Don’t look so dismayed.”

Rossamünd tried to blank his face of worry.

Benedict smiled and scratched the back of his cropped head. “The glimner might have the blue ghasts from a tangle with gudgeons, but from what I hear the fellow is harmless.”

Rossamünd did not share the under-sergeant’s confidence.

10

NUMPS

seltzermen

tradesmen responsible for the maintenance of all types of limulights. Their main role is to make and change the seltzer water used in the same. Among lamplighters, seltzermen have the duty of going out in the day to any lamp reported by the lantern-watch (in ledgers set aside for the purpose) as needing attention and performing the necessary repair. This can be anything from adding new seltzer, to adding new bloom, to replacing a broken pane or replacing the whole lamp-bell.

tradesmen responsible for the maintenance of all types of limulights. Their main role is to make and change the seltzer water used in the same. Among lamplighters, seltzermen have the duty of going out in the day to any lamp reported by the lantern-watch (in ledgers set aside for the purpose) as needing attention and performing the necessary repair. This can be anything from adding new seltzer, to adding new bloom, to replacing a broken pane or replacing the whole lamp-bell.

E

XCEPT for targets in the Toxothanon, Rossamünd had never gone down into the Low Gutter. He had often wanted to explore its workings, but he now descended the double flights of the Medial Stair with flat despondency. A Domesday vigil wasted.

XCEPT for targets in the Toxothanon, Rossamünd had never gone down into the Low Gutter. He had often wanted to explore its workings, but he now descended the double flights of the Medial Stair with flat despondency. A Domesday vigil wasted.

Despite a gathering storm roiling to the south, Rossamünd did not hurry. He took time to stroll through the Low Gutter, fascinated by this hurry-scurry place. There were many here who rarely participated in a vigil-day rest. Great fogs of steam seeped from doorway seals and boiled from the chimneys of the Tub Mill, which stood on the other side of a wide cul-de-sac at the east end of the Toxothanon. It was a-bustle with fullers entering and leaving, burdened with bundles of laundry in varying states of cleanliness. The prentice stood aside for a train of porters hefting loads of clean clothing back to the manse, wondering if any of his own clobber was among them.

Crossing a wide cul-de-sac, the All-About, and passing by the Mule Row, a neat three-story block of servant housing, Rossamünd could hear the hammering of a smith or a cooper, and with this the sawing of a carpenter. In the narrow lane beyond, muleteers trotted their mules in and out of the ass manger, mucking their stalls, scrubbing the animals, feeding them. Beyond the manger rose the near-monumental mass of the magazine, where much of the manse’s black powder was stored. This structure was said to have ten-foot-thick walls of concrete but a roof of flimsy wood, there only to keep out rain. If there was ever an explosion, it would be contained by the walls and erupt through this frangible top far less harmfully into the air.

Dodging a mule and its steaming deposit, Rossamünd made his way across the street to where two besomers sat beneath an awning determinedly binding straw with wire, making ready for brooms.

“Well-a-day to you, young lampsman.What can we do for you?” one of the men called as the prentice approached.

“Hello, sirs,” said Rossamünd, and touched his forehead in respect. Almost everyone in Winstermill was of superior rank to a prentice-lighter. “I seek the lantern store and Mister Numps.”

A queer look passed between the two besomers.

“Do you, then? Well, just keep on your way past us, past the well, and the magazine, through the work-stalls and behind the pitch stand—that large hutch yonder there.You’re looking for the big depository that’s built right against the east-end wall.You want to go through Door 143.”

Bidding thanks, Rossamünd followed the friendly directions and found himself before a low wooden warehouse built beneath the shadow of the Gutter’s eastern battlements. On the rightmost door he found a metal plate that read:

Even as the prentice approached the door the rain suddenly arrived, falling quick and hard. Unprotected by any eave or porch, Rossamünd ignored all polite custom, opened “143” without a knock and ducked inside.

The depot beyond was truly the lantern store, he discovered, as his sight adjusted to the scant light. On either side of him were shelves, ceiling-high and sagging with all the equipment needed to mend and maintain the vialimns or great-lamps. Rows of lamp-bells without their glass stood on their collets in a line or hung on hooks from the roof beams. Whole wrought lantern-posts were laid flat in frames, ready to replace any ruined by time or the action of monsters. There were rolls of chain for mending the winds and with them spools of wire. At the end of this crowded avenue of metal and wood hung a massive rack of tools used for repair work. Chisels and heavy saws, sledgehammers, crowbars, mallets, rivet molds, powerful cutters and clamps and other devices were arranged upon it, all for the singular problems a seltzerman might face.

Despite the rain hammering on the lead-shingle roof, Rossamünd could make out a small, infrequent tinkling in the gloom, like two people touching glasses at a compliment. He could not fathom why some happy pair might be taking a tipple in the dim lantern store. Curious, he followed the sporadic noise deeper into the store. A low, lonely singing, true in tone, deep yet sweet, came through the dust and tools.

Will the Coster sat in posture,

Upon his bed of hay.

Will the Coster spake,“I’ve lost her!”

Head sadly hung to sway.

Such sad posture for Will Coster:

“She ne’er should gone away.”

But Will Coster, he has lost her,

And grieves it ev’ry day.

Upon his bed of hay.

Will the Coster spake,“I’ve lost her!”

Head sadly hung to sway.

Such sad posture for Will Coster:

“She ne’er should gone away.”

But Will Coster, he has lost her,

And grieves it ev’ry day.

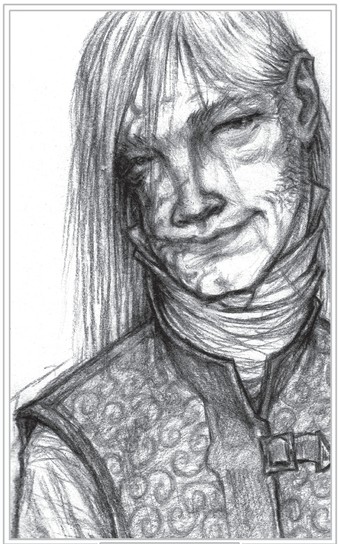

Beguiled, Rossamünd stepped out from among the shadows and equipment and into light. An old-fashioned great-lamp lit the space, with seltzer so new it glowed the color of summer-bleached straw. Cluttered about it was a motley collection of damaged and ruined bright-limns, great-lamps, flares, oil lanterns, even a corroded old censer like those that burned at the gate of Wellnigh House. Right in the middle of it all was the singer. He was alone, sitting on a wicker chair and bent over an engrossing task. He hunched strangely in his seat, his face a dark profile against the seltzer light, his legs pulled up oddly in front. His buff-colored hair was in an advanced state of thinning, and what little he possessed grew lank and thin to his jawline. He was winter-wan, and glimpses of his pallid skull gleamed in the clean light.

There was another “chink,” and the prentice saw the fellow put a small pane of glittering glass upon a stack and then, with the same hand, replace this with another dull piece.This he placed in his lap and, still with the same hand, tipped grit paste from a clay jar on to a cloth laid out on a broad barrel. He did something remarkable then. He put down the jar and, with a deft movement of his leg, picked up the cloth between nimble toes and began to polish. He used his foot—bootless and stockingless even on this inclement day—as easily as another might use a hand.

“H-Hello,” Rossamünd said softly.

The fellow hesitated only briefly then kept polishing, round and round with his toe-gripped cloth. “I felt you there a-shuffling,” he said quietly, almost a whisper, so desperately fragile that Rossamünd stepped closer to hear it better. “Have you come to help me or to hurt me?”

“I—ah . . . to help, I hope.” The prentice smiled nervously to show that he was not a threat.

“You smell like a helper” was the baffling reply.

Thrown by this, Rossamünd stuttered, “Um . . . A-are you M-Mister Numps?”

The fellow looked up and blinked languidly once, showing a shadowy preview of a lopsided face. Rossamünd tried not to gasp or start in alarm, yet he still took an involuntary backward step. The fellow’s face, from the right-hand brow and down, was a-ruin with scars. His cheek was collapsed, the right-side corner of his mouth torn wider than it should have been. The cicatrice flesh went farther, down the man’s neck, mostly hidden by his collar and stock.

“No one has called me ‘mister’ for three years,” Numps said with a sad inward look, speaking with that gentle voice from the left side of his mouth. “But I was a ‘mister’ before. Mister Numption Orphias, Seltzerman 1st Class . . . hmm, that’s who I was before. Just Numps now.”

“Ah . . . well, hello, Mister Numps. I’ve been set duties with you.”

The glimner frowned thoughtfully. “All right then,” he said mildly, and went back to fastidiously polishing the pane in his lap, pressing hard at some stubborn grime. Rossamünd could see that these stacks of glass panes were for the frames of the lamps and lanterns, big and small.

“What can I do, sir?” Rossamünd looked about uncertainly.

“Well, you can tell me what

your

name is, sir,” Numps re-turned, fumbling and dropping his cleaning rag, then picking it up again with a bare foot.

your

name is, sir,” Numps re-turned, fumbling and dropping his cleaning rag, then picking it up again with a bare foot.

NUMPS

Rossamünd forgot himself a moment, transfixed by this simple, uncommon action.

Other books

Shitake Happens: (A Shitake Mystery Series Prequel) by Mason, Patricia

La fiesta del chivo by Mario Vargas Llosa

Infiltrating Your Heart by Kassy Markham

Three Hundred Million: A Novel by Blake Butler

Tribal Ways by Archer, Alex

Love for Now by Anthony Wilson

Maybe Forever (Maybe... Book 3) by Golden, Kim

Don't Sweat the Small Stuff by Don Bruns

Destined by Lanie Bross