Lamplighter (11 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

I wager he

is

hanging about the foundlingery. It’s the kind of weak prank he would do. I am glad to be rid of him!

Rossamünd shook his head, banished any further thoughts of his old foundlingery foe and reread the welcome missive.

is

hanging about the foundlingery. It’s the kind of weak prank he would do. I am glad to be rid of him!

Rossamünd shook his head, banished any further thoughts of his old foundlingery foe and reread the welcome missive.

Threnody looked at him and then at the paper.

“You have received an amiable letter, I see,” she said.

“Aye, miss,” he replied, “all the way from my old home.”

He was well aware that she had received no friendly communication from home: jealousy was writ clear on her face. With a slight cough, Rossamünd put the letter away and began to eat.

While pudding (figgy dowdy filled with raisins and all poured over with a runny, barely sweet sauce) was being served, a summons came for Threnody from the Lady Dolours. Still suffering her fever, the bane had remained as a guest of the Lamplighter-Marshal, watching over the recovering Pandomë and convalescing herself. The messenger—a little lighter’s boy, too young to start his prenticing—delivered his message with many a faltering “beg yer pardon” and clearing of the throat.

“I must go to take my alembants,” Threnody declared to Rossamünd and, under the guidance of the small messenger, departed without another word. As she left, every other set of eyes but Rossamünd’s followed her and their gaze was not kind. She was going to take her plaudamentum, and whatever other draughts wits needed to keep their organs in check.

Now that surely

is

an imposition!

An image of Europe blossomed in Rossamünd’s memory, of her ailing by a dying fire, teeth blackened by the thick treacle she had drunk, dead grinnlings lying near. How glad he was not to be dependent on such foul chemistry.

Now that surely

is

an imposition!

An image of Europe blossomed in Rossamünd’s memory, of her ailing by a dying fire, teeth blackened by the thick treacle she had drunk, dead grinnlings lying near. How glad he was not to be dependent on such foul chemistry.

At the very end of mains was a brief period called castigations. This was the time when the record of that day’s minor infringements was reiterated and impositions meted out. Following centuries-old custom, Grindrod stood at the large double doors of the mess hall and boomed, “Lamplighter-Sergeant-of-Prentices stands at the port!” An ancient civility: the prentices’ mess hall was the refuge of the prentices alone, accessed by those of higher rank only after the senior-most prentice had granted permission.The boys ceased whatever they were doing and sat up straight. Arabis stood. In a clear confident voice he called, “Cross the threshold and bear up to the hearth; this hall bids thee welcome!”

Courtesies complete, Grindrod entered in a fine display of regular military step. With him came Witherscrawl, walking with civilian slouch and bearing a great black ledger—the Defaulters List, in which each day’s misdemeanors were marked. With a look of dark satisfaction, Witherscrawl stood before the great fire, opened the Defaulters List and stared shrewishly at the boys. “On this Maria Diem, being the sixth of Pulvis, HIR 1601 . . . ,” he began, and proceeded to call off all those caught for minor breaches and the appropriate disciplines.

Rossamünd waited for his own name to be called. He knew what was coming.

“

Bookchild

, Rossamünd, prentice-lighter—accused of wasting black powder and of mishandling his firelock, the penalty being one imposition of scullery duties to be performed three nights hence on the ninth of this month, during the appropriate period.”

Bookchild

, Rossamünd, prentice-lighter—accused of wasting black powder and of mishandling his firelock, the penalty being one imposition of scullery duties to be performed three nights hence on the ninth of this month, during the appropriate period.”

Pots-and-pans!

The imposition was a guilty weight in Rossamünd’s innards. He had washed many a dish in his time at the foundlingery, but not as a punishment. Rossamünd stared straight ahead, not lowering his eyes or his chin.

The next day, Threnody spoke very little to anyone but Rossamünd, even then only briefly, as a mere acquaintance and not someone to whom she had bared her soul. The experiences of Noorderbreech and Arabis had quickly schooled the other prentices to leave her alone, and most of the lads began to mutter against her, darkly declaring that girls should not be allowed to be lighters. Even so, there were still some secret doe-eyed looks sent her way, and many sniggering asides when she left the mess hall morning and night to make her treacles. Chin in air, the calendar ignored them all, rather setting her attention firmly on learning her new trade. She proved quickly that she already possessed most of the skills required, and those few she did not know she was apt to learn. Despite having never marched in her life, it took no more than her first afternoon of evolutions to step-regular with as much facility as the rest. It had taken the other prentices more than a week and much cursing and bawling from Grindrod and Benedict to do the same. Rather than being impressed, the boys resented her quick learning and smug self-awareness.Though there had been no open discussion, it became a general accord that none of them wanted her in his prentice-watch.

Moreover, Threnody’s advent posed a disruption to the symmetry of the manse’s fine lists, and any one of the three quartos might be lumbered with her.With the suspension of the nightly prentice-watch, the question as to which Threnody would join remained unanswered.

6

THE LANTERN-WATCH

skold-shot

leaden balls fired from either musket or pistol, and treated with various concoctions of powerful venificants known as gringollsis, particularly devised for the destruction of monsters. These potives are corrosive, damaging the barrels of the firelocks from which they are fired and eating gradually, yet steadily, away at the metal of the ball itself. Left long enough, a skold-shot ball will dissolve completely away. Very effective against most nickers and bogles, some of the best gringollsis actually poison a monster to the degree that it becomes vulnerable to more mundane weapons.

leaden balls fired from either musket or pistol, and treated with various concoctions of powerful venificants known as gringollsis, particularly devised for the destruction of monsters. These potives are corrosive, damaging the barrels of the firelocks from which they are fired and eating gradually, yet steadily, away at the metal of the ball itself. Left long enough, a skold-shot ball will dissolve completely away. Very effective against most nickers and bogles, some of the best gringollsis actually poison a monster to the degree that it becomes vulnerable to more mundane weapons.

A

s winter deepened, the weather had steadily soured. Great squalling showers would blow up from the Grume, or heavy thunderheads roll in over the Sparrow Downs. On the second morning since the carriage attack and Threnody’s arrival, the prentices stepped-regular for Morning Forming out on Evolution Square. The night’s driving rain had blown away to the northeast, leaving murky puddles and a low solemn sky, and Grindrod stepped over a small mire as he stood before them.

s winter deepened, the weather had steadily soured. Great squalling showers would blow up from the Grume, or heavy thunderheads roll in over the Sparrow Downs. On the second morning since the carriage attack and Threnody’s arrival, the prentices stepped-regular for Morning Forming out on Evolution Square. The night’s driving rain had blown away to the northeast, leaving murky puddles and a low solemn sky, and Grindrod stepped over a small mire as he stood before them.

“The Lamplighter-Marshal and I have revised our conclusions,” he called to the two ranks, obediently still. “Knowing yer way on the highroad is too important to yer survival as full-fledged lighters. I told him that ye should never fear to tread the highroad just because of a single theroscade. Such is the lighter’s life, gentlemen,” he declared. “No good will come of keeping ye from it. Therefore, from tonight, the prentice-watch shall resume.”

The murmur that inevitably buzzed among the prentices over breakfast was mostly of excitement, though there was a groan or three of anxious concern. Some of the boys were quietly happy to be kept off the road with monsters threatening. Rossamünd’s six watch-mates showed off the bandages about their arms that covered the small droplet-shaped cruorpunxis they had received the night before. Their marking had been done in evenstalls without much ceremony by Nullifus Drawk, one of the manse’s skolds and its only puctographist. Now even Wheede was boldly pronouncing to the more timorous, “Ye don’t have to worry, chums, if a hob comes a-calling—we’ll see him off for ye!”

For the remainder of the day, under the earnest eye of Benedict, the prentices practiced the handling of a fodicar as tool and as weapon: trail arms, port arms, order arms, shoulder arms, present arms, reverse arms, quarter arms, over and over. Once a fodicar had made no more sense in Rossamünd’s hands than had a harundo stock at Madam Opera’s. Effectual instruction and plenty of time to practice had seen him improve a little, though today this did not prevent him from fumbling badly once and nearly letting his lantern-crook fall to the ground.

At four o’clock that afternoon, at the end of yet more fodicar drill, the prentices formed up on the square for Lale—the time when that night’s lantern-watch got ready to go out to lighting. Their backs to the Low Gutter, they waited anxiously as maids brought out saloop and fruit for sustenance. Waiting for his food, Rossamünd noticed Dolours standing under a tree over on the Officers’ Green, wrapped thickly in furs and observing them all closely. He looked to Threnody to see if she saw her clave-fellow too but the girl was making a distinct show of not noticing the bane. Peering from Dolours to Threnody and back, Arabis and his cronies muttered dark things to each other about the unsuitability of women for the lighting service.

As a post-lentum arrived with its usual hullabaloo, Rossamünd fidgeted and drank his saloop in nervous gulps. Lantern-watch was resuming on the very night his quarter was rostered to serve. Grindrod stood before them. One by one each lad was called forward and, after a pause,Threnody too. She was to be bundled in with him, the other latecomer, to the dismay of his own quarto and the open relief of the other two, lifting their quarto’s number to eight. Rossamünd gave her a quick look as they lined up before the others, but she kept her eyes front, ignoring him.

While Benedict continued drills with the fourteen left behind, Grindrod marched Q Hesiod Gæta to the gates, forming them up in the designated place on the southern edge of the Grand Mead. Lampsmen Assimus, Bellicos and Puttinger were waiting there to take them out for the night’s lighting. Bellicos thrust a box into Rossamünd’s hands, saying simply, “Hold this!”

Taking it, Rossamünd immediately felt a deep unquiet. Looking within he found it contained many musket balls that shimmered a telltale blue-black rather than the usual dull lead-gray.

Skold-shot!

These were bullets treated with pestilent and mordant scripts—poisons and distinct acids made to do monsters far greater harm than an ordinary ball ever could.

Skold-shot!

These were bullets treated with pestilent and mordant scripts—poisons and distinct acids made to do monsters far greater harm than an ordinary ball ever could.

“Before going out tonight,” the lampsman said sourly, “each of ye is to load yer fusil with one of these.”With great respect, he took a pair of privers and, from the box Rossamünd still gripped reluctantly, plucked out a single ball. He held it up for the prentices to see. “Salt lead we call it, or skold-shot if you prefer. I want ye to take one from the box Master Lately here holds just as I have with these here privers, and load it into yer firelocks. Let’s us give any nasty hobnicker a good cause to pause.”

The prentices obeyed, all but Rossamünd; he carried no fusil, for he had the salumanticum. He stood and obediently offered the box for the other lads. Each took a turn and a ball. Even the lampsmen and Grindrod took rounds, filling their own bullet bags from it. When the loading was done, Rossamünd was grateful to pass the foul-smelling box back to Bellicos.

Grindrod seized Threnody with his steely stare. “I am here to tell ye plain hard: if there’s a peep of witting out of ye—even a wee fishing flutter—you’ll be out of the lighters with no coming back!”

The girl lighter frowned truculently in return, but the lamplighter-sergeant appeared not to notice. He paced before the quarto when they had returned their firelocks to their shoulders. “It has been decided that a leer should be sent with us to improve the security of ye precious lambs. Not that

we

needed fancy-eyed gogglers to watch out for us when we were lantern-sticks.”

we

needed fancy-eyed gogglers to watch out for us when we were lantern-sticks.”

Assimus, Bellicos and Puttinger snickered.

Rossamünd struggled to imagine the lamplighter-sergeant as a fumbling, square-gating lantern-stick.

“Ah!” Grindrod looked toward the manse. “Here struts the fellow now.”

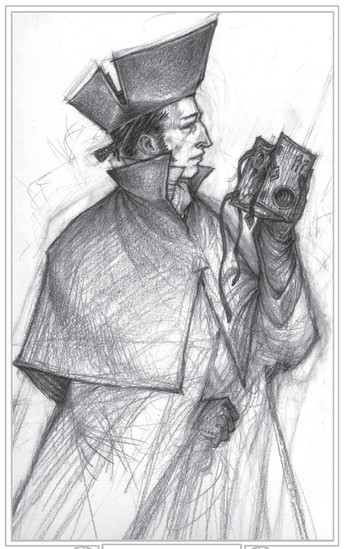

Leaving off a conversation with Dolours, a tall dark fellow stepped toward them. He bore a finely made long-rifle, wore a tall thrice-high upon his head and a dark coachman’s cloak that hid all other attire and accoutrements, including his boots.

Mister Sebastipole!

Here at last was the lamplighter’s agent who had hired Rossamünd back at Madam Opera’s. He looked straight at Rossamünd—with those disquieting red and blue eyes that signified his status as a falseman—as he stopped before the prentices, but if Sebastipole recognized him it did not show.

Here at last was the lamplighter’s agent who had hired Rossamünd back at Madam Opera’s. He looked straight at Rossamünd—with those disquieting red and blue eyes that signified his status as a falseman—as he stopped before the prentices, but if Sebastipole recognized him it did not show.

“Well, Lamplighter’s Agent Sebastipole”—there was a coolness in the manner of Grindrod’s address—“are ye ready to coddle we lowly lighters?”

Other books

Deadly Pack (Deadly Trilogy Book 3) by Ashley Stoyanoff

The Warmest December by Bernice L. McFadden

Memoirs of a Girl Wolf by Lawrence, Xandra

Impulsive by Catherine Hart

Alluvium by Nolan Oreno

RecipeforSubmission by Sindra van Yssel

Poison Tongue by Nash Summers

The Lawman's Betrayal by Sandi Hampton

fml by Shaun David Hutchinson

Camila Winter by The Heart of Maiden