Lad: A Dog (30 page)

Authors: Albert Payson Terhune

“But,” urged Maclay, as they turned back to where Lad still kept his avid vigil, “I still hold you were taking big chances in gambling a thousand dollars and your dog's life that Schwartz would do the same thing again within twenty-four hours. He might have waited a day or two, tillâ”

“No,” contradicted the Master, “that's just what he mightn't do. You see, I wasn't perfectly sure whether it was Schwartz or Romaineâor bothâwho were mixed up in this. So I set the trap at both ends. If it was Romaine, it was worth a thousand dollars to him to have more sheep killed within twenty-four hours. If it was Schwartzâwell, that's why I made him try to hit Lad and why I made him try to kick me. The dog went for him both times, and that was enough to make Schwartz want him killed for his own safety as well as for revenge. So he was certain to arrange another killing within the twenty-four hours if only to force me to shoot Lad. He couldn't steal or kill sheep by daylight. I picked the only hours he could do it in. If he'd gotten Lad killed, he'd probably have invented another sheep-killer dog to help him swipe the rest of the flock, or until Romaine decided to do the watching. Weâ”

“It was clever of you,” cordially admitted Maclay. “Mighty clever, old man! Iâ”

“It was my wife who worked it out, you know,” the Master reminded him. “I admit my own cleverness, of course, onlyâlike a lot of men's moneyâit's all in my wife's name. Come on, Lad! You can guard Schwartz just as well by walking behind him. We're going to wind up the evening's fishing trip by tendering a surprise party to dear genial old Mr. Titus Romaine. I hope the flashlights will hold out long enough for me to get a clear look at his face when he sees us.”

11

WOLF

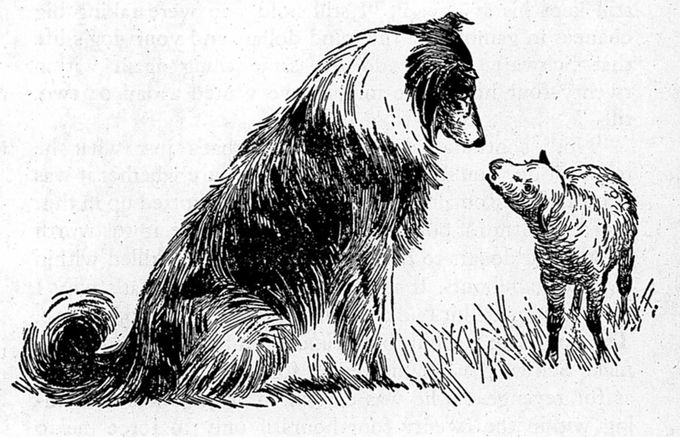

THERE WERE BUT THREE COLLIES ON THE PLACE IN THOSE days. There was a long shelf in the Master's study whereon shimmered and glinted a rank of silver cups of varying sizes and shapes. Two of The Place's dogs had won them all.

Above the shelf hung two huge picture frames. In the center of each was the small photograph of a collie. Beneath each likeness was a certified pedigree, abristle with the red-letter names of champions. Surrounding the pictures and pedigrees, the whole remaining space in both frames was filled with blue ribbonsâthe very meanest bit of silk in either was a semi-occasional “Reserve Winners” while, strung along the tops of the frames from side to side, ran a line of medals.

Cups, medals, and ribbons alike had been won by The Place's two great collies, Lad and Bruce. (Those were their “kennel names.” Their official titles on the A.K.C. registry list were high-sounding and needlessly long.)

Lad was growing old. His reign on The Place was drawing toward a benignant close. His muzzle was almost snow-white and his once graceful lines were beginning to show the oncoming heaviness of age. No longer could he hope to hold his own, in form and carriage, with younger collies at the local dog shows where once he had carried all before him.

Bruceâ“Sunnybank Goldsmith”âwas six years Lad's junior. He was tawny of coat, kingly of bearing; a dog without a fault of body or of disposition; stately as the boar-hounds that the painters of old used to love to depict in their portraits of monarchs.

The Place's third collie was Lad's son, Wolf. But neither cup nor ribbon did Wolf have to show as an excuse for his presence on earth, nor would he have won recognition in the smallest and least exclusive collie show.

For Wolf was a collie only by courtesy. His breeding was as pure as was any champion's, but he was one of those luckless types to be found in nearly every litterâa throwback to some forgotten ancestor whose points were all defective. Not even the glorious pedigree of Lad, his father, could make Wolf look like anything more than he wasâa dog without a single physical trait that followed the best collie standards.

In spite of all this he was beautiful. His gold-and-white coat was almost as bright and luxuriant as any prize-winner's. He had, in a general way, the collie head and brush. But an expert, at the most casual glance, would have noted a shortness of nose and breadth of jaw and a shape of ear and shoulder that told dead against him.

The collie is supposed to be descended direct from the wolf, and Wolf looked far more like his original ancestors than like a thoroughbred collie. From puppyhood he had been the living image, except in color, of a timber wolf and it was from this queer throwback trait that he had won his name.

Lad was the Mistress' dog. Bruce was the Master's. Wolf belonged to the Boy, having been born on the latter's birthday.

For the first six months of his life Wolf lived at The Place on sufferance. Nobody except the Boy took any special interest in him. He was kept only because his better-formed brothers had died in early puppyhood and because the Boy, from the outset, had loved him.

At six months it was discovered that he was a natural watchdog. Also that he never barked except to give an alarm. A collie is, perhaps, the most excitable of all large dogs. The veriest trifle will set him off into a thunderous paroxysm of barking. But Wolf, the Boy noted, never barked without strong cause.

He had the rare genius for guarding that so few of his breed possess. For not one dog in ten merits the title of watchdog. The duties that should go with that office are far more than the mere clamorous announcement of a stranger's approach, or even the attacking of such a stranger.

The born watchdog patrols his beat once in so often during the night. At all times he must sleep with one ear and one eye alert. By day or by night he must discriminate between the visitor whose presence is permitted and the trespasser whose presence is not. He must know what class of undesirables to scare off with a growl and what class needs stronger measures. He must also know to the inch the boundaries of his own master's land.

Few of these things can be taught; all of them must be instinctive. Wolf had been born with them. Most dogs are not.

His value as a watchdog gave Wolf a settled position of his own on The Place. Lad was growing old and a little deaf. He slept, at night, under the piano in the music room. Bruce was worth too much money to be left at large in the night time for any clever dog thief to steal. So he slept in the study. Rex, a huge mongrel, was tied up at night, at the lodge, a furlong away. Thus Wolf alone was left on guard at the house. The piazza was his sentry box. From this shelter he was wont to set forth three or four times a night, in all sorts of weather, to make his rounds.

The Place covered twenty-five acres. It ran from the highroad, a furlong above the house, down to the lake that bordered it on two sides. On the third side was the forest. Boating parties, late at night, had a pleasant way of trying to raid the lakeside apple orchard. Tramps now and then strayed down the drive from the main road. Prowlers, crossing the woods, sometimes sought to use The Place's sloping lawn as a short cut to the turnpike below the falls.

For each and all of these intruders Wolf had an ever-ready welcome. A whirl of madly pattering feet through the dark, a snarling growl far down in the throat, a furry shape catapulting into the airâand the trespasser had his choice between a scurrying retreat or a double set of white fangs in the easiest-reached part of his anatomy.

The Boy was inordinately proud of his pet's watchdog prowess. He was prouder yet of Wolf's almost incredible sharpness of intelligence, his quickness to learn, his knowledge of word meaning, his zest for romping, his perfect obedience, the tricks he had taught himself without human tutelageâin short, all the things that were a sign of the brain he had inherited from Lad.

But none of these talents overcame the sad fact that Wolf was not a show dog and that he looked positively underbred and shabby alongside of his sire or of Bruce. Which rankled at the Boy's heart; even while loyalty to his adored pet would not let him confess to himself or to anyone else that Wolf was not the most flawlessly perfect dog on earth.

Undersized (for a collie), slim, graceful, fierce, affectionate, Wolf was the Boy's darling, and he was Lad's successor as official guardian of The Place. But all his youthful life, thus far, had brought him nothing more than thisâ while Lad and Bruce had been winning prize after prize at one local dog show after another within a radius of thirty miles.

The Boy was duly enthusiastic over the winning of each trophy; but always, for days thereafter, he was more than usually attentive to Wolf to make up for his pet's dearth of prizes.

Once or twice the Boy had hinted, in a veiled, tentative way, that young Wolf might perhaps win something, too, if he were allowed to go to a show. The Master, never suspecting what lay behind the cautious words, would always laugh in good-natured derision, or else he would point in silence to Wolf's head and then to Lad's.

The Boy knew enough about collies to carry the subject no further. For even his eyes of devotion could not fail to mark the difference in aspect between his dog and the two prize-winners.

One July morning both Lad and Bruce went through an hour of anguish. Both of them, one after the other, were plunged into a bathtub full of warm water and naphtha soapsuds and Lux, and were scrubbed right unmercifully, after which they were rubbed and curried and brushed for another hour until their coats shone resplendent. All day, at intervals, the brushing and combing were kept up.

Lad was indignant at such treatment, and he took no pains to hide his indignation. He knew perfectly well, from the undue attention, that a dog show was at hand. But not for a year or more had he himself been made ready for one. His lake baths and his daily casual brushing at the Mistress' hands had been, in that time, his only form of grooming. He had thought himself graduated forever from the nuisance of going to shows.

“What's the idea of dolling up old Laddie like that?” asked the Boy, as he came in for luncheon and found the Mistress busy with comb and dandy brush over the unhappy dog.

“For the Fourth of July Red Cross Dog Show at Ridgewood tomorrow,” answered his mother, looking up, a little flushed from her exertions.

“But I thought you and Dad said last year he was too old to show any more,” ventured the Boy.

“This time is different,” said the Mistress. “It's a specialty show, you see, and there is a cup offered for âthe best

veteran

dog of any recognized breed.' Isn't that fine? We didn't hear of the Veteran Cup till Dr. Hooper telephoned to us about it this morning. So we're getting Lad ready. There

can't

be any other veteran as splendid as he is.”

veteran

dog of any recognized breed.' Isn't that fine? We didn't hear of the Veteran Cup till Dr. Hooper telephoned to us about it this morning. So we're getting Lad ready. There

can't

be any other veteran as splendid as he is.”

“No,” agreed the Boy, dully, “I suppose not.”

He went into the dining room, surreptitiously helped himself to a handful of lump sugar and passed on out to the veranda. Wolf was sprawled half asleep on the driveway lawn in the sun.

The dog's wolflike brush began to thump against the shaven grass. Then, as the Boy stood on the veranda edge and snapped his fingers, Wolf got up from his soft resting place and started toward him, treading mincingly and with a sort of swagger, his slanting eyes half shut, his mouth agrin.

“You know I've got sugar in my pocket as well as if you saw it,” said the Boy. “Stop where you are.”

Though the Boy accompanied his order with no gesture nor change of tone, the dog stopped dead short ten feet away.

“Sugar is bad for dogs,” went on the Boy. “It does things to their teeth and their digestions. Didn't anybody ever tell you that, Wolfie?”

The young dog's grin grew wider. His slanting eyes closed to mere glittering slits. He fidgeted a little, his tail wagging fast.

“But I guess a dog's got to have

some

kind of consolation purse when he can't go to a Show,” resumed the Boy. “Catch!”

some

kind of consolation purse when he can't go to a Show,” resumed the Boy. “Catch!”

As he spoke he suddenly drew a lump of sugar from his pocket and, with the same motion, tossed it in the direction of Wolf. Swift as was the Boy's action, Wolf's eye was still quicker. Springing high in air, the dog caught the flung cube of sugar as it flew above him and to one side. A second and a third lump were caught as deftly as the first.

Other books

Playing with Fire - A Sports Romance by Lydia De Luca

Second Chance Brides by Vickie Mcdonough

Face of Death by Kelly Hashway

Big Sky by Kitty Thomas

Worlds Without End by Caroline Spector

Feel The Fire (Unforgettable Series) by Byrd, Adrianne

You Smiled by Scheyder, S. Jane

Impossible Girl (Sexy Nerd Boys #2.5) by K. M. Neuhold

Drowning Ophelia (Immoral Dracula) by Natsumi, Eva

A Perfect Spy by John le Carre