Lad: A Dog (14 page)

Authors: Albert Payson Terhune

The Master went out first, to get the car and bring it around to the side exit of the Garden. The Mistress gathered up Lad's belongingsâhis brush, his dog biscuits, etc., and followed, with Lad himself.

Out of the huge building, with its reverberating barks and yells from two thousand canine throats, she went. Lad paced, happy and majestic, at her side. He knew he was going home, and the unhappiness of the hideous day dropped from him.

At the exit, the Mistress was forced to leave a deposit of five dollars, “to insure the return of the dog to his bench” (to which bench of agony she vowed, secretly, Lad should never return). Then she was told the law demands that all dogs in New York City streets shall be muzzled.

In vain she explained that Lad would be in the streets only for such brief time as the car would require to journey to the One Hundred and Thirtieth Street ferry. The door attendant insisted that the law was inexorable. So, lest a policeman hold up the car for such disobedience to the city statutes, the Mistress reluctantly bought a muzzle.

It was a big, awkward thing, made of steel, and bound on with leather straps. It looked like a rattrap. And it fenced in the nose and mouth of its owner with a wicked crisscross of shiny metal bars.

Never in all his years had Lad worn a muzzle. Never, until today, had he been chained. The splendid eighty-pound collie had been as free of The Place and of the forests as any human; and with no worse restrictions than his own soul and conscience put upon him.

To him this muzzle was a horror. Not even the loved touch of the Mistress' dear fingers, as she adjusted the thing to his beautiful head, could lessen the degradation. And the discomfort of itâa discomfort that amounted to actual pain âwas almost as bad as the humiliation.

With his absurdly tiny white forepaws, the huge dog sought to dislodge the torture implement. He strove to rub it off against the Mistress' skirt. But beyond shifting it so that the forehead strap covered one of his eyes, he could not budge it.

Lad looked up at the Mistress in wretched appeal. His look held no resentment, nothing but sad entreaty. She was his deity. All his life she had given him of her gentleness, her affection, her sweet understanding. Yet, today, she had brought him to this abode of noisy torment, and had kept him there from morning to dusk. And nowâjust as the vigil seemed endedâshe was tormenting him, to nerve-rack, by this contraption she had fastened over his nose. Lad did not rebel. But he besought. And the Mistress understood.

“Laddie, dear!” she whispered, as she led him across the sidewalk to the curb where the Master waited for the car. “Laddie, old friend, I'm just as sorry about it as you are. But it's only for a few minutes. Just as soon as we get to the ferry, we'll take it off and throw it into the river. And we'll never bring you again where dogs have to wear such things. I promise. It's only for a few minutes.”

The Mistress, for once, was mistaken. Lad was to wear the accursed muzzle for much,

much

longer than “a few minutes.”

much

longer than “a few minutes.”

“Give him the back seat to himself, and come in front here with me,” suggested the Master, as the Mistress and Lad arrived alongside the car. “The poor old chap has been so cramped up and pestered all day that he'll like to have a whole seat to stretch out on.”

Accordingly, the Mistress opened the door and motioned Lad to the back seat. At a bound the collie was on the cushion, and proceeded to curl up thereon. The Mistress got into the front seat with the Master. The car set forth on its six-mile run to the ferry.

Now that his face was turned homeward, Lad might have found vast interest in his new surroundings, had not the horrible muzzle absorbed all his powers of emotion. The Milan Cathedral, the Taj Mahal, the Valley of the Arno at sunsetâthese be sights to dream of for years. But show them to a man who has an ulcerated tooth, or whose tight new shoes pinch his soft corn, and he will probably regard them as Lad just then viewed the twilight New York streets.

He was a dog of forest and lake and hill, this giant collie with his mighty shoulders and tiny white feet and shaggy burnished coat and mournful eyes. Never before had he been in a city. The myriad blended noises confused and deafened him. The myriad blended smells assailed his keen nostrils. The swirl of countless multicolored lights stung and blurred his vision. Noises, smells and lights were all jarringly new to him. So were the jostling masses of people on the sidewalk and the tangle and hustle of vehicular traffic through which the Master was threading the car's way with such difficulty.

But, newest and most sickening of all the day's novelties was the muzzle.

Lad was quite certain the Mistress did not realize how the muzzle was hurting him nor how he detested it. In all her dealings with himâor with anyone or anything elseâthe Mistress had never been unkind; and most assuredly not cruel. It must be she did not understand. At all events, she had not scolded or forbidden when he had tried to rub the muzzle off. So the wearing of this new torture was apparently no part of the Law. And Lad felt justified in striving again to remove it.

In vain he pawed the thing, first with one foot, then with both. He could joggle it from side to side, but that was all. And each shift of the steel bars hurt his tender nose and tenderer sensibilities worse than the one before. He tried to rub it off against the seat cushionâwith the same distressing result.

Lad looked up at the backs of his gods, and whined very softly. The sound went unheard, in the babel of noise all around him. Nor did the Mistress or the Master turn around, on general principles, to speak a word of cheer to the sufferer. They were in a mixup of crossways traffic that called for every atom of their attention, if they were to avoid collision. It was no time for conversation or for dog-patting.

Lad got to his feet and stood, uncertainly, on the slippery leather cushion, seeking to maintain his balance, while he rubbed a corner of the muzzle against one of the supports of the car's lowered top. Working away with all his might, he sought to get leverage that would pry loose the muzzle.

Just then there was a brief gap in the traffic. The Master put on speed, and, darting ahead of a delivery truck, sharply rounded the corner into a side street.

The car's sudden twist threw Lad clean off his precarious balance on the seat, and hurled him against one of the rear doors.

The door, insecurely shut, could not withstand the eighty-pound impact. It burst open. And Lad was flung out onto the greasy asphalt of the avenue.

He landed full on his side, in the muck of the roadway, with a force that shook the breath clean out of him. Directly above his head glared the twin lights of the delivery truck the Master had just shot past. The truck was going at a good twelve miles an hour. And the dog had fallen within six feet of its fat front wheels.

Now, a collie is like no other animal on earth. He is, at worst, more wolf than dog. And, at best, he has more of the wolf's lightning-swift instinct than has any other breed of canine. For which reason Lad was not, then and there, smashed, flat and dead, under the fore wheels of a three-ton truck.

Even as the tires grazed his fur, Lad gathered himself compactly together, his feet well under him, and sprang far to one side. The lumbering truck missed him by less than six inches. But it missed him.

His leap brought him scramblingly down on all fours, out of the truck's way, but on the wrong side of the thoroughfare. It brought him under the very fender of a touring car that was going at a good pace in the opposite direction. And again, a leap that was inspired by quick instinct alone, lifted the dog free of this newest death menace.

He halted and stared piteously around in search of his deities. But in that glare and swelter of traffic, a trained human eye could not have recognized any particular car. Moreover, the Mistress and Master were a full half block away, down the less crowded side street, and were making up for lost time by putting on all the speed they dared, before turning into the next westward traffic artery. They did not look back, for there was a car directly in front of them, whose driver seemed uncertain as to his wheel control, and the Master was maneuvering to pass it in safety.

Not until they had reached the lower end of Riverside Drive, nearly a mile to the north, did either the Master or Mistress turn around for a word with the dog they loved.

Meantime, Lad was standing, irresolute and panting, in the middle of Columbus Circle. Cars of a million types, from flivver to trolley, seemed to be whizzing directly at him from every direction at once.

A bound, a dodge, or a deft shrinking back would carry him out of one such perilâbarely out of itâwhen another, or fifty others, beset him.

And, all the time, even while he was trying to duck out of danger, his frightened eyes and his pulsing nostrils sought the Mistress and the Master.

His eyes, in that mixture of flare and dusk, told him nothing except that a host of motors were likely to kill him. But his nose told him what it had not been able to tell him since morningânamely, that, through the reek of gasoline and horseflesh and countless human scents, there was a nearness of fields and woods and water. And, toward that blessed mingling of familiar odors he dodged his threatened way.

By a miracle of luck and skill he crossed Columbus Circle, and came to a standstill on a sidewalk, beside a low gray stone wall. Behind the wall, his nose taught him, lay miles of meadow and wood and lakeâCentral Park. But the smell of the Park brought him no scent of the Mistress nor of the Master. And it was themâinfinitely more than his beloved countrysideâthat he craved. He ran up the street, on the sidewalk, for a few rods, hesitant, alert, watching in every direction. Then, perhaps seeing a figure in the other direction that looked familiar, he dashed at top speed, eastward, for half a block. Then he made a peril-fraught sortie out into the middle of the traffic-humming street, deceived by the look of a passing car.

The car was traveling at twenty miles an hour. But, in less than a block, Lad caught up with it. And this, in spite of the many things he had to dodge, and the greasy slipperiness of the unfamiliar roadway. An upward glance, as he came alongside the car, told him his chase was in vain. And he made his precarious way to the sidewalk once more.

There he stood, bewildered, heartsickâlost!

Yes, he was lost. And he realized itârealized it as fully as would a city dweller snatched up by magic and set down amid the trackless Himalayas. He was lost. And Horror bit deep into his soul.

The average dog might have continued to waste energy and risk life by galloping aimlessly back and forth, running hopefully up to every stranger he met; then slinking off in scared disappointment and searching afresh.

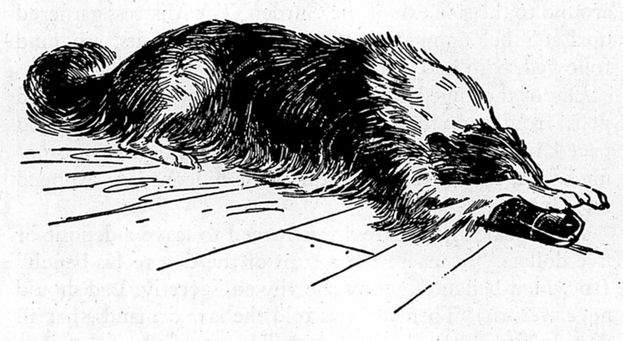

Lad was too wise for that. He was lost. His adored Mistress had somehow left him, as had the Master, in this bedlam placeâall alone. He stood there, hopeless, head and tail adroop, his great heart dead within him.

Presently he became aware once more that he was still wearing his abominable muzzle. In the stress of the past few minutes Lad had actually forgotten the pain and vexation of the thing. Now, the memory of it came back, to add to his despair.

And, as a sick animal will ever creep to the woods and the waste places for solitude, so the soul-sick Lad now turned from the clangor and evil odors of the street to seek the stretch of country land he had scented.

Over the gray wall he sprang, and came earthward with a crash among the leafless shrubs that edged the south boundary of Central Park.

Here in the Park there were people and lights and motorcars, too, but they were few, and they were far off. Around the dog was a grateful darkness and aloneness. He lay down on the dead grass and panted.

The time was late February. The weather of the past day or two had been mild. The brown-gray earth and the black trees had a faint odor of slow-coming spring, though no nostrils less acute that a dog's could have noted it.

Through the misery at his heart and the carking pain from his muzzle, Lad began to realize that he was tired, also that he was hollow from lack of food. The long day's ordeal of the Dog Show had wearied him and had worn down his nerves more than could a fifty-mile run. The nasty thrills of the past half hour had completed his fatigue. He had eaten nothing all day. Like most high-strung dogs at a show, he had drunk a great deal of water and had refused to touch a morsel of food.

He was not hungry even now for, in a dog, hunger goes only with peace of mind, but he was cruelly thirsty. He got up from his slushy couch on the dead turf and trotted wearily toward the nearest branch of the Central Park lake. At the brink he stooped to drink.

Soggy ice still covered the lake, but the mild weather had left a half-inch skim of water over it. Lad tried to lap up enough of this water to allay his craving thirst. He could not.

Other books

Rufus Drake: Duke of Wickedness by Carole Mortimer

That Dirty Dog and Other Naughty Stories for Good Boys and Girls by Christopher Milne

The Time of Her Life by Jeanie London

Bill, héroe galáctico by Harry Harrison

Suspicions of the Heart by Hestand, Rita.

Always with You (WIth You Trilogy) by Sable, R. J.

Crashing Down by Kate McCaffrey

Her Last Night of Innocence by India Grey

Lay It Down: Bastards MC Series Boxed Set by Carina Adams

Mindfulness by Gill Hasson