Knife of Dreams (2 page)

Authors: Robert Jordan

31 The House on Full Moon Street

EPILOGUE: Remember the Old Saying

The sweetness of victory and the bitterness of defeat are alike a knife of dreams.

—From

Fog and Steel

by Madoc Comadrin

K

NIFE OF

D

REAMS

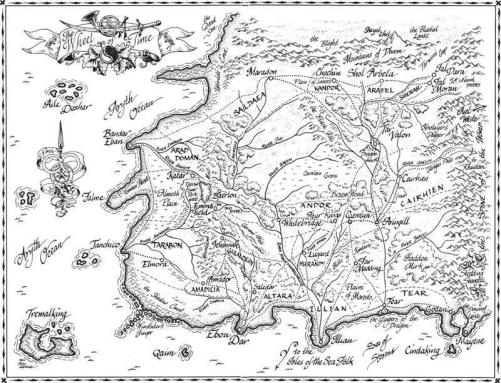

The sun, climbing toward midmorning, stretched Galad’s shadow and those of his three armored companions ahead of them as they trotted their mounts down the road that ran straight through the forest, dense with oak and leatherleaf, pine and sourgum, most showing the red of spring growth. He tried to keep his mind empty, still, but small things kept intruding. The day was silent save for the thud of their horses’ hooves. No bird sang on a branch, no squirrel chittered. Too quiet for the time of year, as though the forest held its breath. This had been a major trade route once, long before Amadicia and Tarabon came into being, and bits of ancient paving stone sometimes studded the hard-packed surface of yellowish clay. A single farm cart far ahead behind a plodding ox was the only sign of human life now besides themselves. Trade had shifted far north, farms and villages in the region dwindled, and the fabled lost mines of Aelgar remained lost in the tangled mountain ranges that began only a few miles to the south. Dark clouds massing in that direction promised rain by afternoon if their slow advance continued. A red-winged hawk quartered back and forth along the border of the trees, hunting the fringes. As he himself was hunting. But at the heart, not on the fringes.

The manor house that the Seanchan had given Eamon Valda came into view, and he drew rein, wishing he had a helmet strap to tighten for excuse. Instead he had to be content with re-buckling his sword belt, pretending

that it had been sitting wrong. There had been no point to wearing armor. If the morning went as he hoped, he would have had to remove breastplate and mail in any case, and if it went badly, armor would have provided little more protection than his white coat.

Formerly a deep-country lodge of the King of Amadicia, the building was a huge, blue-roofed structure studded with red-painted balconies, a wooden palace with wooden spires at the corners atop a stone foundation like a low, steep-sided hill. The outbuildings, stables and barns, workmen’s small houses and craftsfolks’ workshops, all hugged the ground in the wide clearing that surrounded the main house, but they were nearly as resplendent in their blue-and-red paint. A handful of men and women moved around them, tiny figures yet at this distance, and children were playing under their elders’ eyes. An image of normality where nothing was normal. His companions sat their saddles in their burnished helmets and breastplates, watching him without expression. Their mounts stamped impatiently, the animals’ morning freshness not yet worn off by the short ride from the camp.

“It’s understandable if you’re having second thoughts, Damodred,” Trom said after a time. “It’s a harsh accusation, bitter as gall, but—”

“No second thoughts for me,” Galad broke in. His intentions had been fixed since yesterday. He was grateful, though. Trom had given him the opening he needed. They had simply appeared as he rode out, falling in with him without a word spoken. There had seemed no place for words, then. “But what about you three? You’re taking a risk coming here with me. A risk you have no need to take. However the day runs, there will be marks against you. This is my business, and I give you leave to go about yours.” Too stiffly said, but he could not find words this morning, or loosen his throat.

The stocky man shook his head. “The law is the law. And I might as well make use of my new rank.” The three golden star-shaped knots of a captain sat beneath the flaring sunburst on the breast of his white cloak. There had been more than a few dead at Jeramel, including no fewer than three of the Lords Captain. They had been fighting the Seanchan then, not allied with them.

“I’ve done dark things in service to the Light,” gaunt-faced Byar said grimly, his deep-set eyes glittering as though at a personal insult, “dark as moonless midnight, and likely I will again, but some things are too dark to be allowed.” He looked as if he might spit.

“That’s right,” young Bornhald muttered, scrubbing a gauntleted hand

across his mouth. Galad always thought of him as young, though the man lacked only a few years on him. Dain’s eyes were bloodshot; he had been at the brandy again last night. “If you’ve done what’s wrong, even in service to the Light, then you have to do what’s right to balance it.” Byar grunted sourly. Likely that was not the point he had been making.

“Very well,” Galad said, “but there’s no fault to any man who turns back. My business here is mine alone.”

Still, when he heeled his bay gelding to a canter, he was pleased to have them gallop to catch him and fall in alongside, white cloaks billowing behind. He would have gone on alone, of course, yet their presence might keep him from being arrested and hanged out of hand. Not that he expected to survive in any case. What had to be done, had to be done, no matter the price.

The horses’ hooves clattered loudly on the stone ramp that climbed to the manor house, so every man in the broad central courtyard turned to watch as they rode in: fifty of the Children in gleaming plate-and-mail and conical helmets, most mounted, with cringing, dark-coated Amadician grooms holding animals for the rest. The inner balconies were empty except for a few servants who appeared to be watching while pretending to sweep. Six Questioners, big men with the scarlet shepherd’s crook upright behind the sunflare on their cloaks, stood close around Rhadam Asunawa like a bodyguard, away from the others. The Hand of the Light always stood apart from the rest of the Children, a choice the rest of the Children approved. Gray-haired Asunawa, his sorrowful face making Byar look fully fleshed, was the only Child present not in armor, and his snowy cloak carried just the brilliant red crook, another way of standing apart. But aside from marking who was present, Galad had eyes for only one man in the courtyard. Asunawa might have been involved in some way—that remained unclear—yet only the Lord Captain Commander could call the High Inquisitor to account.

Eamon Valda was not a large man, but his dark, hard face had the look of one who expected obedience as his due. As the very least he was due. Standing with his booted feet apart and his head high, command in every inch of him, he wore the white-and-gold tabard of the Lord Captain Commander over his gilded breast- and backplates, a silk tabard more richly embroidered than any Pedron Niall had worn. His white cloak, the flaring sun large on either breast in thread-of-gold, was silk as well, and his gold-embroidered white coat. The helmet beneath his arm was gilded and worked with the flaring sun on the brow, and a heavy gold ring on his left

hand, worn outside his steel-backed gauntlet, held a large yellow sapphire carved with the sunburst. Another mark of favor received from the Seanchan.

Valda frowned slightly as Galad and his companions dismounted and offered their salutes, arm across the chest. Obsequious grooms came running to take their reins.

“Why aren’t you on your way to Nassad, Trom?” Disapproval colored Valda’s words. “The other Lords Captain will be halfway there by now.” He himself always arrived late when meeting the Seanchan, perhaps to assert that some shred of independence remained to the Children—finding him already preparing to depart was a surprise; this meeting must be very important—but he always made sure the other high-ranking officers arrived on time even when that required setting out before dawn. Apparently it was best not to press their new masters too far. Distrust of the Children was always strong in the Seanchan.

Trom displayed none of the uncertainty that might have been expected from a man who had held his present rank barely a month. “An urgent matter, my Lord Captain Commander,” he said smoothly, making a very precise bow, neither a hair deeper nor higher than protocol demanded. “A Child of my command charges another of the Children with abusing a female relative of his, and claims the right of Trial Beneath the Light, which by law you must grant or deny.”

“A strange request, my son,” Asunawa said, tilting his head quizzically above clasped hands, before Valda could speak. Even the High Inquisitor’s voice was doleful; he sounded pained at Trom’s ignorance. His eyes seemed dark hot coals in a brazier. “It was usually the accused who asked to give the judgment to swords, and I believe usually when he knew the evidence would convict him. In any case, Trial Beneath the Light has not been invoked for nearly four hundred years. Give me the accused’s name, and I will deal with the matter quietly.” His tone turned chill as a sunless cavern in winter, though his eyes still burned. “We are among strangers, and we cannot allow them to know that one of the Children is capable of such a thing.”

“The request was directed to me, Asunawa,” Valda snapped. His glare might as well have been open hatred. Perhaps it was just dislike of the other man’s breaking in. Flipping one side of his cloak over his shoulder to bare his ring-quilloned sword, he rested his hand on the long hilt and drew himself up. Always one for the grand gesture, Valda raised his voice so that even people inside probably heard him, and declaimed rather than merely spoke.

“I believe many of our old ways should be revived, and that law still stands. It will always stand, as written of old. The Light grants justice because the Light is justice. Inform your man he may issue his challenge, Trom, and face the one he accuses sword-to-sword. If that one tries to refuse, I declare that he has acknowledged his guilt and order him hanged on the spot, his belongings and rank forfeit to his accuser as the law states. I have spoken.” That with another scowl for the High Inquisitor. Maybe there really was hatred there.