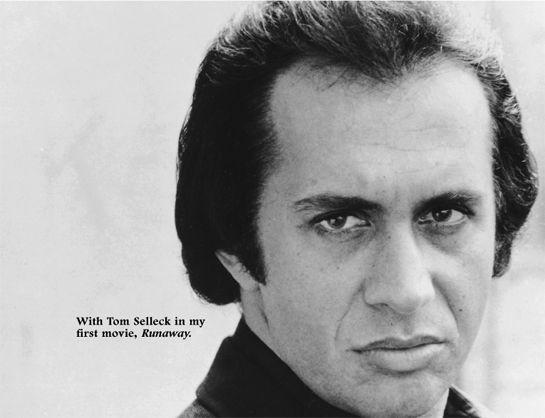

Kiss and Make-Up (31 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

We eventually caved in and accepted Vinnie. If we had hoped that taking him into the fold might lessen the headache of dealing

with him, those hopes were not fulfilled. First of all, he wanted to hold on to his name, Vinnie Cusano. I told him at the outset that it was not a good idea: it sounded like a fruit vendor, and fairly or unfairly, rock and roll is about image. Everybody else had a nondescript name where you couldn’t figure out their ethnicity or anything else about them. I had changed my name and he would have to do the same. He finally agreed that his name was problematic, but then he had his own ideas about what the new one should be. He wanted to be called Mick Fury. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that he wasn’t qualified to do this kind of stuff, that he should just show up on time and make lots of money.

Vinnie worsened. He didn’t sign his contract, ever. Finally we told him he had to sign. It was an offer of employment. He could be in the band or not, but we didn’t want to discuss it. It was nonnegotiable. There was a calendar too: with

Creatures

done, we either had to lose the window of a tour or go off on tour with this guy. We decided, rightly or wrongly, to go on the tour with him. Paul designed Vinnie’s ankh makeup and his Wiz character.

Paul and Eric Carr on the way to Brazil in 1981 to play an outdoor concert.

KISS was now

made up of Eric Carr, Vinnie Vincent, Paul, and me. We liked

Creatures of the Night

and hoped for the best. But the album did poorly. We booked an American tour, and it was the least successful tour we’d ever done. The music scene was changing: acts like Michael Jackson and the Clash were in ascent, and no one showed up to hear us play. In North America, that is; abroad, especially in South America, we played to the biggest audiences we’d ever played, stadiums full of people. Even though the experience was depressing in some respects, it opened our eyes to the idea that no one city and no one marketplace is definitive. If you’re not making

it in the United States, go to Brazil. If you’re not making it in Colombia, try Italy.

The biggest change at that time was the rise of MTV. Music was being overtaken by a certain visual style. We had been a visual band since the beginning, but oddly, our idea of visual panache didn’t necessarily translate in the world of early 1980s rock and roll, which was dominated by hair-metal bands. Hair bands were dominant because they gave younger teenagers, and especially younger girls, access to a kind of rock music that had been considered too dangerous for them before. Girls who were only thirteen and fourteen were having their first brushes with sexuality, and for their early crushes, they were turning to these hair-metal bands, to Bon Jovi, to Poison. As it turned out, we had one band member who was perfectly suited for this transition: Paul Stanley. He was at home being that kind of front man, dancing on the stage. So for the first time in our career, we did exactly what we saw happening with other bands. It’s not worth debating the justification, worrying over originality and inspiration. We were a working band. Instead of being leaders, we decided basically to follow.

At around that same time, we decided to drop the one visual element that had been associated with KISS most strongly and from the very beginning: our makeup. When we started working on

Lick It Up

, it was a good time musically. We had Michael James Jackson producing once again, and Vinnie Vincent was our guitarist and a contributing songwriter. Vinnie and Paul were particularly successful during this period; the two of them wrote “Lick It Up,” the title track from that album. In the middle of recording the album, more or less out of nowhere, Paul pulled me aside and said, “Gene, I think it’s time to take our makeup off.” His reasoning was sound—with all the personnel changes, we had moved farther and farther away from plausible characters. Vinnie Vincent’s character, the Wizard, wasn’t sticking with fans the way the Demon or the Starchild had. “Let’s prove something to the fans,” Paul said. “Let’s go and be a real band without makeup.”

I reluctantly agreed. I didn’t know if it was going to work or not, but I heard what Paul was saying—there was nowhere else for us to go. We did a photo session just to see what it would look like. We looked straight into the camera lens. We were defiant. I made one small concession to the fans—I stuck out my tongue, to try to keep something that connected us with the past, to remind fans that we weren’t a brand-new band.

We decided to unveil ourselves live on MTV. First, superimposed over our faces, were photos of us in full KISS makeup. As the veejay announced each of our names, the makeup photos dissolved to our bare faces. We made the best of it, but I was scared stiff.

Lick It Up

was released and immediately tripled the sales of

Creatures of the Night.

It went platinum and we were soon filling up concert halls again. This was clearly a new lease on life.

Eric Carr must have felt as if the ground were moving under him every time he took a step. He was thrilled to join the KISS he knew and loved, but the first record he played on was a concept album. The second was

Creatures of the Night.

Then, with the third record he played on, KISS took off the makeup.

After we took off our makeup and embraced the MTV age, the crowd changed dramatically. Back in the early days, we had started off with a bizarre crowd, opening for other bands, and KISS was perceived as a dangerous band of rock-metal rebels. When we became more mainstream, the toys and the games brought us a very young crowd. At some point Mom and Dad would show up with their three-year-old kids. It became like the circus. The 1980s brought yet another shift. Suddenly we were popular with teenage girls. They came to the show. They got in front. They screamed. And

sometimes they seemed to want to do more than just scream; some of them were clearly groupies in training. For the record, I should say that I never went after the underage ones—enough legal-age girls were showing up. But these young girls would come backstage. They were always around. I would walk into my room, and usually there would be a girl there.

The early and mid-1980s were a troubling time for me in some respects. My connection to KISS, the dominant part of my life for a decade, began to change. Mainly what happened was that I started to get lost. I didn’t know how I was supposed to act, because the no-makeup version of the band was an entirely new idea. Paul was in his prime. He was very comfortable being who he was, because in some ways Paul is the same offstage as onstage. For those couple of years it became more his band. Paul was always the guy who spoke in the interviews. When you saw photos of KISS, they tended more and more to be photos of Paul. Still, if I stuck my tongue out enough times, I would eventually get in the frame.

It’s important to be clear about what happened. Paul didn’t push me out of the spotlight. He would never do that to me. It’s just that his ability to capture the public’s attention increased as the music scene changed. My reaction was to try to muscle my way back into the spotlight by buying some truly outlandish androgynous clothing. It didn’t work, not the way I wanted it to. It just made me look like a football player in a tutu.

This period also gave me an opportunity to watch Paul at work, and it was an interesting process. Paul’s sense of things is what you’d more traditionally think of as the female perspective. Call me simplistic, but I think women are less interested in the endgame, in winding up in bed with somebody, than in just being recognized for being attractive. Paul is more like that. Paul is less interested in whether the girl winds up in bed with him than in whether she finds him good-looking. I’m not interested in whether she finds me attractive; I’m only interested in whether she winds up in bed with me. Paul and I both like chocolate cake, so you would think we’re alike, but we’re completely different. He only likes the frosting. I hate the frosting—I only like the stuff you can chew, the devil’s

food. So if you walk by a cake and see the devil’s food missing, you know I’ve been there. If you walk by and see the frosting missing, Paul’s been there. Between the two of us, we can split a whole cake. So in a very real way, we are opposite pieces of the same puzzle. Somehow it worked.