Kiss and Make-Up (18 page)

Authors: Gene Simmons

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Musicians, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Rock Stars

Afterward she told me that her name was Star, that someday she would be a star, and that her last name was Stowe. We stayed up all night long, and when morning came and it was time to leave, she asked me what she should do. I remember saying something about sending photos of herself to Hugh Hefner. I was out of touch with her for about six months. Then one of our road crew showed me an issue of

Playboy.

The centerfold was Star Stowe; she described herself as a “one-band woman” and said some very nice things about me. I contacted her, and for a time she was my companion on the road. We had terrific times. We went to movies together. We went to clubs. We ate. We danced. We couldn’t keep our hands off each other.

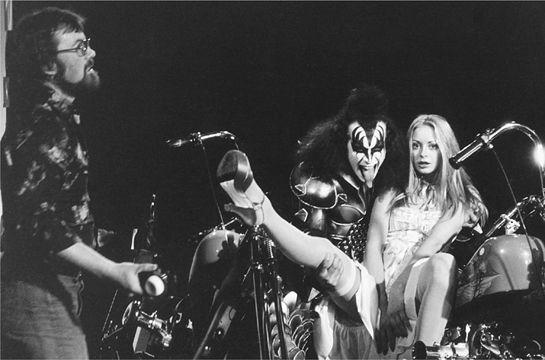

The beautiful Star Stowe in 1975. Fin Costello, the photographer, is on the left.

(photo credit 7.5)

After a time I lost touch with her. Years later I ran into her at one of our concerts. She had been through some hard times, had not saved any money, and seemed sadder than I had ever seen her. Later on I looked her up and was stunned to find that she had passed away.

The relative failure

of the “Rock and Roll All Nite” single disappointed us slightly, but it didn’t scare us, because we knew exactly what we had to do. We had to go right back on the road, which was where we were strongest and connected with our audience most powerfully. This time there was an extra wrinkle: we had decided to record some of the shows and release them as a live album. We had the three studio albums, but we never felt as though they captured the band. They were merely documents. For the full KISS experience, we needed to let fans have a taste of our live show—not only the theatrical elements but the power of the band.

The recordings that would become

Alive!

were drawn from a number of concerts, including shows in New Jersey and Iowa. The majority of the album, though, was taken from a late March show at Cobo Hall in Detroit. In some ways the decision to tape the Detroit concerts was the easiest one we ever made. A city is never just a city. It is always defined by the people who live in it and by what they do for a living, which then in a very real way affects their lifestyle. Because New York is a cosmopolitan city, it was the birthplace of Studio 54. Southern cities were more repressed in some ways and wilder in others. Detroit, being the hub of the auto industry, was antifashion, much more meat and potatoes. I wouldn’t be surprised if McDonald’s sold more hamburgers in Detroit than anywhere else. It’s very blue collar, a real middle-American metropolis. The big stars that emerged out of Detroit through the late 1960s and early 1970s—the MC5, Ted Nugent, Bob Seger, and Grand Funk Railroad—were similar bands: loud and passionate, with minimal pretention and a bit of grittiness. Detroit is all about no-nonsense music. From our very first record, Detroit had taken us to heart immediately. People in New York and Los Angeles misread us—they affected a certain sophistication and felt that we weren’t up to their standards. But Detroit understood our mix of fun and energy from the start.

We were one of the biggest bands in the world.

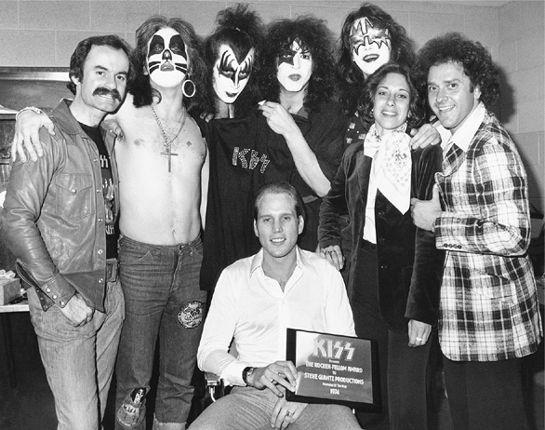

(photo credit 81.1)

After the Detroit show, we were presented with an award and went to a party thrown in our honor. There was plenty of action at the party—lots of booze, music, and women. I wasn’t interested in the booze; I had had my fill of music for the day; and I even had my female companion for the night, a writer from

Creem

magazine who was doing a feature article about the band. I was ready to leave with her, when I spied the waitress moving through the crowd with a plate of brownies. My sweet tooth got the better of me, and I pounced on those suckers. I must have eaten six or seven of them before I had my fill. Within five minutes I became Gene in Wonderland. Immediately my head shrank to the size of an apple. My feet ballooned to the size of boards. My hands grew bigger the longer I stared at them. I grew frightened, took the hand of my female companion, and ran out to the waiting limo.

Once inside I became very thirsty for milk. I had to have some, and within a block of the concert hall, in a seedy part of Detroit, we pulled up to an all-night diner. Inside it was quiet, and there were a few people with their heads down, either eating or drinking coffee. I stepped up to the counter, thinking that my voice couldn’t be heard because my vocal cords must have shrunk along with my head. I screamed at full volume,

“May I have a glass of milk, please?”

It scared the pants off the waitress. Everyone at the place, now startled, looked up. I was embarrassed. I thought they were all looking at how small my head had gotten. I left the diner, dove back into the car, and thanked God my female companion knew where the hotel was. She got us there, and as I was walking down the hallway, propped up by her, every step felt as though I were walking through a funhouse mirror.

When we got to the door to my room, I couldn’t fit my key in the lock. My key was now the size of an anvil, and the keyhole no bigger than the eye of a needle. The only saving grace that night, when we finally got into bed, was that I was finally proud of my manhood and couldn’t imagine anything getting bigger.

Alive!

almost did not come out. Casablanca had taken a bath on a record called

Best Moments of the Tonight Show

, a double album that consisted of highlights from Johnny Carson’s talk show. (Ironically enough, this record was put together by Joyce Biawitz, our former comanager and the woman who would soon be Mrs. Neil Bogart.) Even though we were the label’s prize act, there wasn’t a whole lot of money to go around. There have always been rumors that the

Alive!

record was substantially reworked in the studio. It’s not true. We did touch up the vocal parts and fix some of the guitar solos, but we didn’t have the time or money to completely rework the recordings. What we wanted, and what we got, was proof of the band’s rawness and power.

Alive!

was released in September 1975 and immediately moved up the charts. Sales eventually went to four million. Amazingly, the live record produced our first big single, a concert version of “Rock and Roll All Nite.” Almost overnight we went from being a working band with a record contract and a devoted following to being national superstars. The lasting effect of the live album went beyond KISS, in fact—it affected the entire rock industry. Before

Alive!

bands didn’t really release concert albums as legitimate product. They were almost always put out to fulfill contracts. We were one of the first bands to really care about the idea and to package it accordingly: when the album came out, it had a gatefold showing all three studio records and pictures of handwritten notes from all the band members. Within three years, many more of these elaborate live packages appeared, including

Frampton Comes Alive

and

Cheap Trick at Budokan

(which included a little homage to us in a song called “Surrender” with the lyric “Rock and rolling, got my KISS records out”). Live records became mandatory for 1970s superstars, and we led the way.

We received an award for breaking the attendance record at Cobo Hall in Detroit (held by Elvis). From left to right, Bill Aucoin, Peter, me, Paul, Ace, and Joyce and Neil Bogart, with Steve Glantz, seated.

After the massive success of

Alive!

, we knew that we had to deliver a grand statement. We wanted a studio record that would top all our previous efforts. To achieve that, we brought in Bob Ezrin, who was already well known as a producer for his work with Alice Cooper and would later produce Pink Floyd’s

The Wall.

We started recording in the Record Plant in New York in January 1976—only five months after the release of

Alive!

Up until we met Bob Ezrin, we were leery of letting anybody else have a say as to what we should record. That included management, record companies, producers, anybody. Bob Ezrin was the first and continues to be the only producer who ever really had an effect on the band.

It’s hard to say why we let Bob have so much control, yet it’s also easy. It wasn’t about his track record. It’s never about a track record. It is more about the fact that when somebody has an idea and can communicate that idea as effectively as Bob, they automatically command a certain respect. Other bands have stories about meeting up with producers who teach them how to be professionals—before these producers came along, they were noble savages, beating on

their guitars and just hoping for the best. It wasn’t like that with KISS. We had known what we were doing since the beginning. Bob didn’t make us go faster. In fact, if anything he slowed the process down considerably. But it was the way he slowed it down that was impressive. At one point I remember him stopping us in the middle of a rehearsal. “Okay,” he said. “Do you guys know how to tune your instruments?”

We were all self-taught musicians. We said, “Of course—here’s how you tune them.”

He frowned. “No,” he said. “There’s another way to tune instruments, which is pitch-perfect. It’s called harmonic tuning.” And he showed us how to do it, which we had never seen in our lives. It was like going back to school, or to summer camp—he carried a whistle around, and whenever he wanted to get our attention, he would say, “Campers!” Every time we thought we had done enough to satisfy him, he would come at us with something else.

In some ways, he was quite a disciplinarian. When he didn’t think we were getting a handle on something, he would send us outside the studio. Paul and I were excited, because we knew the experience was making the band better. We were rubbing our hands together, thinking

Oh, boy, this is going to a place we haven’t been.

It was a really good adventure because we recognized that whatever we were doing, even though it was a step forward, it still sounded like KISS, but better than before. We literally heard the record coming together there in the studio, and it was the best version of the band to that point.