Kingshelm (Renegade Druid Cycle Book 1)

Read Kingshelm (Renegade Druid Cycle Book 1) Online

Authors: George Hatt

Chapter Twelve - Mithrandrates

Chapter Nineteen - Mithrandrates

Chapter Twenty-Three - Paardrac

Chapter Twenty-Four - Paardrac

Chapter Twenty-Five - Mithrandrates

Chapter Twenty-Six - Mithrandrates

Chapter Thirty-One - Mithrandrates

Chapter Thirty-Four - Mithrandrates

Chapter Forty-Three - Mithrandrates

KINGSHELM

George Hatt

Copyright © 2015 George Hatt

All rights reserved.

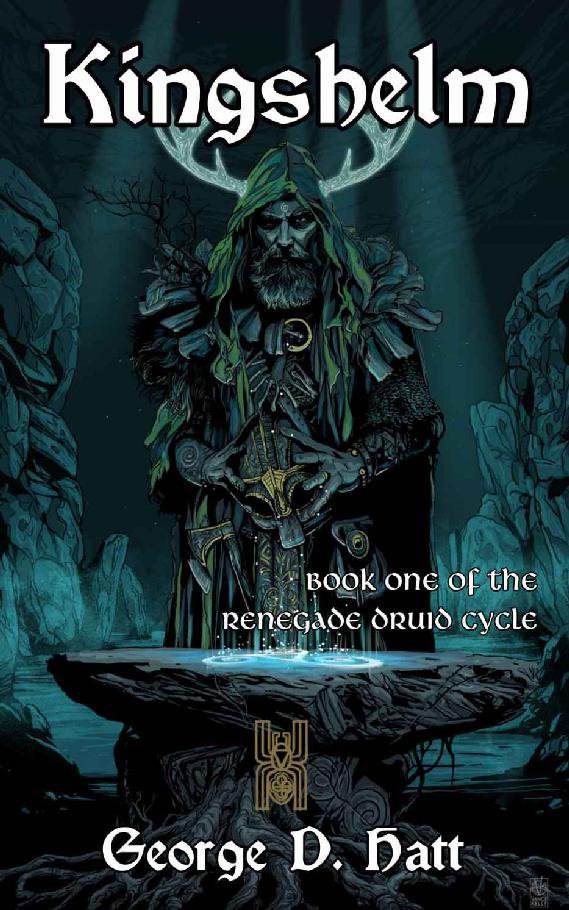

Cover art by Vance Kelly

For Papa.

If this book is a work of any quality, I have several people to thank for helping me make it that way.

I want to first thank Ru Deyo for giving me the ideas of the M’Tarr and the Vehir—as well as other peoples in our shared multiverse, but I won’t mention them lest I post series spoilers at the front of my first damn book! He was also there for the whole writing process as a sounding board, a beta reader, and an in-multiverse fact checker.

I also want to thank beta readers who helped me flog the draft into something resembling a book. Jordan Robertson and Kevin Kline generously gave their written comments and their great patience as I drafted this thing. Samantha Bellows pointed out something icky in an early draft that I subsequently deleted. Good catch!

Big props go to Vance Kelly for producing stunning cover art that makes this look like the kind of book I’d want to pick up and read, and I’m a picky reader.

And through it all—the early mornings and late nights of drafting and editing, the vicious bouts of writer’s block, and my hubris-fueled crowing as I finished yet another chapter—has been my beautiful wife Cindy.

Thank you all.

Bold was she and beautiful, and serenely fearless in her wrath.

—Donald A. Mackenzie

The talisman that has let my mind rove beyond the confines of this accursed tower shows me much, especially of the distant past. For instance, I watch now as dragons and their riders swoop down in fiery aerial cavalcade on formations of dwarves arrayed for battle in the plains below. Dwarves. Ha! Those stern folk called themselves the Haughrav in the days before their nations were crushed, and would split the skulls of anyone who named them “dwarf.” But this vision of fire and blood—of dragons and dwarves—though fascinating, bears little relevance to the volume at hand.

As is customary for books of this genre, I shall begin this

Supplement One to the Rise, Decline and Fall of the Mergovan Empire

with an expository prologue that will, I hope, elucidate some of the more arcane aspects of the world of Fentress and its inhabitants during the Latter Warring States Era without overburdening the reader with superfluous detail.

Readers of my previous volumes know full well that I have treated the social, economic, military, and thaumaturgical aspects of the Empire’s history in what the lay reader might consider excruciating detail (though I and my editors believe that the text was more than amply footnoted. In further defense of the admittedly ponderous volumes of the

Rise

, let me remind the reader that the books, and indeed the present volume, were written while I am exiled to Ersetu. I languish in a prison tower rising from infinite planes of gray dust for what is not actually eternity, but so closely approximates it that one could not call it otherwise without lapsing into rank pedantry. I have nothing if not time, in other words. I would ask for some indulgence from you, Dear Reader.)

However, the thoroughly objective treatment I give the events of that epoch in the several volumes of the

Rise

tends to obscure any emotional connection the reader may have to the happenings outlined therein. Names, dates and places march by in such rapid succession at certain points of the narrative that one is hard pressed to keep up with them unless a pen and notebook are close at hand and liberally used. The present volume, as well as the volumes to follow, will fill that gap in the scholarship by describing actions, thoughts and feelings of a few of the principal actors in the events covered in the

Rise

. Whereas I sought to give an objective view in the previous volumes,

Supplement One

provides the subjective points of view that aid us in our attempt to answer that most vexing of questions facing students of Imperial history: “Why?”

My research methods for

Supplement One

differ from those of my previous work, and I confess they approach the voyeuristic, depending chiefly upon this device that the grimoires name the Stone of Sight. Simply put, the Stone allows me to see through space and time, to read thoughts, to

feel

others’ emotions as if they were my own. Other historians say with poetic flourish that they have developed comfortable, old friendships with the subjects of their narratives. With the aid of the Stone, I have in fact done just that.

During the writing of this volume, I strove mightily to suppress my urge toward exposition of that which my subjects had no knowledge. I feel that such a subjective treatment of the men, women and monsters in the following pages offers a verisimilitude that allows the reader “walk along the path” with those vibrant beings who have heretofore been reduced to flat caricatures populating other history books.

To fully appreciate the treatment I give the prominent figures and their roles as told in

Supplement One

, the reader would do well to peruse the volumes of the

Rise

and at the very least familiarize himself with the timelines therein. A summary and concordance to that series is in the works but, alas, remains incomplete.

Other tomes of use to the general reader include my

Magic: The Technology of the Gods

;

Myth, Magic and the Mind: Man’s Creation of the Gods

; and

Before the Fiery Chariots:

A Natural History of Fentress

(the appendices on the mass extinctions wrought by our ancestors show how thoroughly they transformed the world for their use—the familiar truly devoured the alien in our distant past). Scholarly readers should be familiar enough with my catalog to decide for themselves which of my denser works will be of most utility in their studies.

As always, I must list those to whom I am indebted for the completion of this work. First and foremost, I thank Our Lady of Chaos for taking pity on me in this prison tower and supplying me with a library and enchanted instruments equal to the task of keeping my mind occupied during my exile in the blackness of Ersetu.

Time, study and reflection during my imprisonment have shown me how deeply I sank in error during my life as a mere human. I was led astray by my lust for domination and ultimately trapped by my own eldritch tinkering. To rule a world with an army of the undead, after all, destroys that very thing which is sought to be ruled. I know this now thanks to Her, and I now focus my not inconsiderable energies and intellect on the pursuit of knowledge rather than fulfilling a ravenous desire for power.

I also must thank the paladin Hamfast, one of the Heroes of Old, for offering me his mercy and allowing me the beneficence of his truly honorable sense of justice. After my final defeat at the Shoraz-Athar Rift, he alone impressed upon the Companions of Mahurin that I should be imprisoned here rather than hurled into the Infernal Pits for an eternity of suffering.

My hatred for Ashara has cooled significantly during my eternal, yet timeless, imprisonment. My criticisms of her are now purely academic and free of the vitriol that I had allowed to seep into my earlier works.

Deva Astrotolic

Tower on the Astral Sands

Kyntha’s Feast Day, 1,523

rd

year of my imprisonment

Barryn

Flickering candlelight and pungent incense smoke cast a solemn gloom in the ancient temple where Barryn of Clan Riverstar held vigil over the ceremonial bronze weapons he would soon carry on his journey to the Neverfar Realms.

The boy of 16 winters sat cross-legged on a bear fur, mustering his spiritual power for the coming ordeal. Spicy-sweet curls of smoke undulated in the ruddy half-darkness and wafted his prayers to the stern gods he revered: Udric, chief of the gods, the bringer of knowledge, order and wisdom; Kyntha, goddess of the White Moon, fertility and the waters; and Taern, god of war, self-sacrifice and ruler of the great Red Moon. Other gods and powers moved in the heavens and the mysterious realms between light and shadow, such as Mahurin, the mighty warrior whose resplendent chariot carried the sun across the heavens. Elemental beings, wood spirits, the heroes of old, the fey and even the feared devas were no strangers to the people of the Caeldrynn. They watched the affairs of mortals but seldom interfered. If anything drew their gaze, it was when the son of a druid neared manhood and prepared for his rites of passage.

Barryn shifted, flexed his broad shoulders and allowed himself to glance around. His dark, shoulder-length hair brushed lightly over his tunic. Surrounding him, thirteen megaliths stood guard around a stone altar carved with knotted serpents and geometric figures, staring down upon the boy and his weapons like a council of giants. The whole ancient, weathered circle formed the heart of the great timber-framed Hall of the Gods which was built many thousands of years after the stones were set in the hallowed ground. Great wooden pillars held the roof and rafters of the circular hall, all covered with carvings of writhing dragons and gnarled, grasping trees. Here sacrifices were made, oracles were read and handfasting vows exchanged. Here the very power of the gods was invoked and great magic worked in times of war and suffering. The temple inspired awe in the laity of the Clan, who only visited on special occasions and to observe holy days throughout the year. But for Barryn, it was a classroom and refuge from the drudgery of village life.

All Caeldrynn youth passed a series of tests of their character and skill before they were considered adults by their kin and village. Children of hunters organized their first hunt, while children of blacksmiths crafted their first weapons or tools. Barryn was preparing for his first vision quest, but he would not go alone. An experienced druid and an adept would be accompany him to protect him and to help interpret his visions. This was the dangerous stage in Barryn’s education when he and the Clan would learn whether his path truly was that of the druids.

Resting upon the stone altar before him, the young druid candidate’s bronze short sword and a quiver of bronze-tipped arrows glimmered red in the candlelight. Barryn would take the ceremonial weapons into the wilderness to hunt and to defend himself against the dangerous but mortal creatures that lurked in the woods. Steel, however, repelled the fey spirits of the forest and was thus forbidden to him on the vision quest—the spirits and otherfolk were welcome companions on this journey, not threats to be warded off.

If the visions and the signs indicated against it, or if Barryn panicked during his journey to the Spirit Realms, his training as a druid would cease. Then even Barryn's mother, the High Druidess of Clan Riverstar, could not grant him his dream of speaking with the Holy Ones as a druid. He would choose another trade and be given over as an apprentice to a master for his secular, mundane training. Barryn took a deep breath, laden with the scent of bear fur mixed with incense, and exhaled it in small puffs, letting the cleansing breath wash the nagging thoughts failure away.