Kijana (20 page)

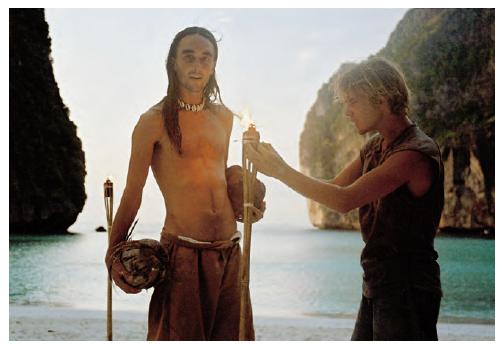

My best friend and me.

A fleeting moment of paradise - they did exist!

Unfortunately there was no Ben Harper or Pearl Jam on the stereo, just some metal gongs hanging from the branch of a sweeping tree on which the local men tapped a beat. These gongs made a dong noise each time they were hit, creating strange, atmospheric music, and giving the event its strange name.

On the dance floor the local women and men took it in turns to do a traditional dance. Nearly all the dances involved a scarf held behind the head between outstretched arms. The dancers' heads slowly rotated from side to side, like those clowns in a sideshow attraction, while their feet pounded the dusty ground in time to the gongs. The scarf would then be handed to someone in the audience, who would take the floor and attempt to mimic the dance that had just been performed.

Some of the surfers looked like they'd seen it all before, doing the dance very well. One of the younger surfers even had his arm around an old lady as if she was his grandma.

Someone then yelled an order, summoning all the women from the audience onto the floor. Maria joined the group as they formed a circle and proceeded to move in a clockwise direction while they kicked out their legs in a cancan-style dance.

While this was going on, the Australian guy plonked himself down in Maria's seat and surrendered the jug of sopi. He'd had his fill. Despite his drunken state, he introduced himself as Dave and explained that he'd helped organise the night with the family that was hosting the evening. He already knew we were the âyoung people' from the ketch, complimenting us on our boat.

As he told us what the dances meant, we realised he actually lived with the family in the house. He explained he was trying to earn the community some extra income by organising these dong nights.

That immediately aroused our interest, so we asked if we could question him on camera. He wasn't keen on that idea, instead changing the subject. He was curious as to how such young people got to be cruising through Indonesia without any parents or adults. We told him about the Kijana adventure and what we were doing. He asked what Kijana meant.

âIt's Swahili for young people,' we replied in unison, we'd got so used to answering the question.

âHow old

are

you guys?' he asked.

I pointed to Maria: âShe's 22, Beau's 19.'

âI'm 22,' Josh continued, then, pointing at me, said: âHe's 20 . . . actually 21 today.' It made me stop and think. He was right, it was so easy to forget. I was 21.

Dave nearly jumped out of his seat in excitement. He called out in Indonesian to an old man standing nearby who came over and listened to Dave explain something.

âThis is Samuel,' Dave announced. âHe's the boss of this family.'

The man was small with a pointy face. He smiled at me and put out his hand to shake mine. The man then pointed to a boy walking towards us and called him over.

Dave introduced us. âThis is Rianto, Samuel's son. He's 21 today as well!'

He explained the circumstances to Rianto, who seemed delighted. He made some elaborate hand gestures, then shook my hand affectionately. I introduced Beau, and Josh and pointed out Maria who was still dancing. Dave was still very excited by my news. He continued speaking in Indonesian before turning back to us.

âAre you having a party? You can't turn 21 and not have a party.'

âWell, this has been a pretty good day so far,' I replied.

He continued speaking to Samuel, who was nodding his head.

âWe'll organise a party for you,' Dave declared. He was speaking so quickly we could almost see his mind ticking over. âWe can have a few goats and make it a feast for everyone, I know a perfect spot down by the beach. It'll look great for the camera. You can film that instead.'

I wasn't sure what he was more excited about â my birthday or the fact that he'd been able to divert attention from himself. No matter. I was flattered by his enthusiasm. Rianto smiled at me like a brother. It was set.

The following morning I went to meet Dave at the house, as arranged. Daylight revealed the dry and scrubby landscape that had been shrouded in darkness the night before. I passed several small shacks on the way as I retraced the bus route. It was much further than I remembered.

As I arrived at the house, Rianto was sitting on the porch strumming a guitar. His eyes lit up when he saw me. The whole family came out and I was handed a cup of locally grown coffee.

âIs Dave here?' I asked. None of them spoke English but they understood Dave's name. I was shown into the house, which was almost completely bare. The floors were well-worn, smooth concrete, while a few cloth mats and a plastic chair in the corner were the only furniture in the main living room.

I was directed through a door to the right, where I found Dave asleep on a bed under a mosquito net. There were a few books on the windowsill and a single bag, which appeared to amount to his total possessions.

âDavid,' Rianto softly called. I left the room to let him get up in peace. A short while later he emerged, ducking under a doorway obviously not built for westerners. He was nursing a hangover but still seemed genuinely pleased to see me.

He finished the introductions he'd started the previous evening. Samuel's wife, Shysi, I recognised as one of the women who had been dancing the previous night. Another old man with a friendly smile was called Ahmad. He was Samuel's brother. Then there was Rianto, the boy who shared my birth date; his older sister Empy, who was about 25; her husband Ronny and daughter Aalyyah.

With the formalities over, Samuel and Ahmad led Rianto, Dave and me towards the beach, where they revealed the location they had in mind for my party.

It was a special site, Dave told me. Out towards the water lay hundreds of giant clam shells, each half a metre wide and facing upwards, towards the sky. For more than a century they'd been used to evaporate sea water so the precious salt that remained could be harvested for cooking. The men set to work clearing the hardy shrubs around the area, gathering them into a pile for burning.

While they did this, Dave showed me a half-built traditional hut of about 3 metres by 3 metres. As we inspected the hut, he told me the extraordinary tale of how he had come to be there.

Dave discovered Nembrala as a much younger man. He was like any of the surfers staying in the village, working in Australia merely to get enough money to travel through Indonesia surfing. He met Samuel and his family on one of his visits to Indonesia. Empy was only 11 years old at the time and bedridden with malaria, fighting for her life. With no local health system and very few doctors, there was nothing Samuel could do to help his daughter. The few doctors who could help lived in the major cities and Samuel could never afford their services, let alone the cost of getting her to them. She was destined to die within months.

Her plight so touched Dave that he returned to Australia to resume his job as a bricklayer, returning a few months later with money and a stash of medicine. With Dave's help, Empy slowly escaped the clutches of death and returned to normal health. She was now an adult with her own family. Samuel had thanked him the only way he could â he offered him the site we now stood on. With an ocean view and scrubby surroundings, Dave was in paradise. He now planned to retire and live permanently in Nembrala and the hut was to be his home.

Samuel and his family insisted they build him a big house but Dave refused. All he wanted was a little grass hut, his surfboard and a horse on which to ride to the surf. Their attempt to convince him to get a motorbike was met with a staunch refusal. They used petrol, he argued, and why buy that stuff when a horse could eat from the surrounding bush. He not only looked like Paul Hogan, he lived like Crocodile Dundee.

I asked Dave what had led him to his decision to live a âprimitive' life, as he described it.

He explained how he'd become fed up with aspects of modern life in Australia. For instance, he was sick of busting his gut laying bricks for houses, only to see them demolished within a few years because property values had risen, and a better house could be built in its place. Such waste angered him.

âYou spend your whole life building stuff only to see it get knocked down,' he said.

He figured he'd be alive for another 20 years, so he wanted to go out leading a life he believed in. It was an extraordinary story. I wished Josh had been there with the camera.

We both stared out to the water until I finally broke the silence.

âSo, how should we pay for this party?'

He looked at me sheepishly. I sensed the topic of money was a difficult one considering what he'd just told me.

âWell, I've had a word to the guys and they can't afford to give away any goats. A month ago half their stock was stolen by a neighbour, so I can't ask them for another two goats. What I was thinking is that you could cover the payment for the goats, and the rest they will cover â vegetables, rice and sopi.'

He paused to think, then continued, his enthusiasm returning: âAgung will bring the dongs, and that reminds me, I've gotta find Trent. He's married to an Indonesian lady and can play guitar pretty good. So if that's all right with you, I'll give 'em the go-ahead for tomorrow night, then all we have to do is spread the word, yeah?'

âSounds good to me. How much is a goat?'

âTwenty bucks or so, not much, but it's heaps for them. We'll have them in the morning, so come along and watch them prepare them if you like.'

On my way back I called into the home-stay to invite all the surfers.

While I was away, Beau and Maria had been cleaning the boat while Josh had set insect traps throughout the forward cabin. I told them of the plan and we scooted in the dinghy to the three other nearby yachts, inviting them to come along. Sam and Gabby on the small catamaran already knew. The word was spreading!

We spent the afternoon filming our attempts at surfing, with Josh donning the scuba gear to film the underwater shots. Dinner on board in the cool air capped off another day in paradise. I took a moment to think how far removed this was from the early stages of the trip.

By the morning it was obvious the bug traps would need some refinement. Josh and Beau had battled it out with the bed bugs all night, with Josh embarking on a bug-swiping spree using a library card to collect and squash them. Beau again opted to use a cup to capture them alive. Josh claimed 12 lives, Beau's tally was two. They sat in the cup on the galley bench, awaiting further argument on their fate.

By midmorning we were ready to go. We packed the camera gear and headed along the island in the dinghy to where the clam shells sat in the sun. When we arrived I discovered Beau had with him an empty Mars Bar wrapper which contained the two bugs. He solemnly walked up the beach and let them go in the tall grass. I hoped they didn't settle in Dave's hut.

We made the short walk to where the party preparations had already begun. The women from the nearby houses were already dressed in their best clothes. What immediately struck me was that they all wore the same coloured lipstick. It was an odd sight to see them in the cooking shed, leaning over a searing fire and grinding chilli paste in such delicate attire.

We all had a shot of sopi to kick-start the day, then followed the men to gather the goats.

The goats we were about to butcher had arrived the previous evening by motorbike. Ronny had picked them up from a relative who lived 20 kilometres away. The legs of each goat were tied together and wrapped around his stomach, one at the front and one at the back as he rode home.

The goats were herded from a pen to beneath a tree near the house. Within half an hour the two bleating goats had their throats cut and their blood drained into a bowl. They were then skinned and cut into pieces we could carry. Josh sat transfixed behind the camera as Ronny carried out the work. The best cuts went straight to the women in the shed while the heads and blood were kept by the men.