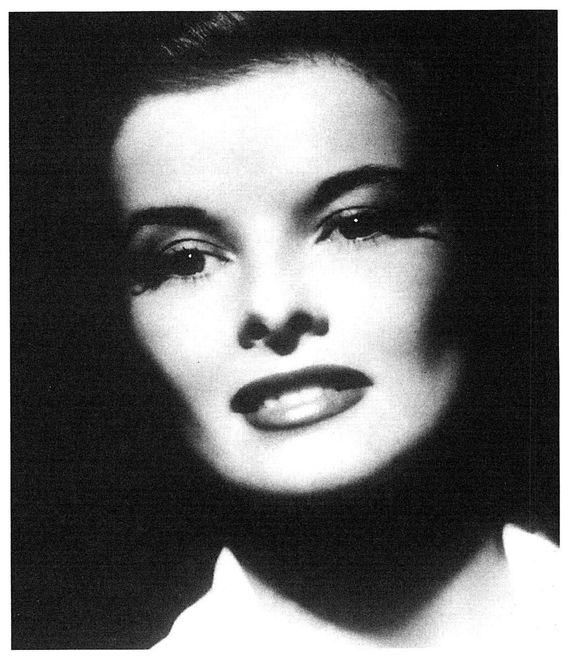

Kate Remembered (17 page)

Authors: A. Scott Berg

To help Hepburn confront some of her career frustrations, La Cava decided that the play within the film, in which Terry Randall ultimately triumphs, should be Hepburn's old bête noire,

The Lake

. “It was a brilliant idea,” Kate realized the moment he suggested it, “because it allowed me to take my most miserable moment in the theater and turn it into something fun.” As a result of La Cava's instincts, audiences would forever remember Hepburn fondly, not foolishly, for uttering, “The calla lilies are in bloom again. . . .”

The Lake

. “It was a brilliant idea,” Kate realized the moment he suggested it, “because it allowed me to take my most miserable moment in the theater and turn it into something fun.” As a result of La Cava's instincts, audiences would forever remember Hepburn fondly, not foolishly, for uttering, “The calla lilies are in bloom again. . . .”

The film was nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award and still plays like gangbusters, but it was a box-office disappointmentâfinancially successful, but only barely so. For the small profit margin, industry pundits blamed Hepburn. Believing she had at least bounced back from intense unpopularity, RKO figured the way to keep reversing the trend was to make her even bouncier. They cast her in a farce called

Bringing Up Baby

.

Bringing Up Baby

.

Like most “screwball comedies,” the plot to this wisecracking, nonsensical love story crossed the traditional lines of social class and sexual roles. In this case, a persistent heiress sets her madcap on a paleontologist, losing an important dinosaur bone and gaining a pet leopard named Baby along the way. Howard Hawks, who had theretofore been making his name with action-packed dramas, turned to producing as well as directing with this comedy, creating the template for most of the best pictures of his career. He liked his comedic leading men to be good-looking and good-natured and his leading ladies to be fast-talking and slightly androgynous, able to wear the pants in the picture. He kept every scene galloping at a breakneck pace to a finish in which all the disparate pieces of plot fall into place.

“Now I had a very strong body,” Kate said of herself, “and that allowed me to play broad, physical comedy very well, because I had complete confidence in my moves. And I was haughty enough in the mind of the public that it would be funny for them to see me roll in the mud or have the back of my dress ripped off.” Cary Grant, who had become Hollywood's number-one romantic comedy star upon the release of

The Awful Truth,

was an obvious choice for David Huxley, a Harold Lloydâlike professor. “We were very good together,” Kate observed, “because it looked as though we were having a great deal of fun together, which we were.”

The Awful Truth,

was an obvious choice for David Huxley, a Harold Lloydâlike professor. “We were very good together,” Kate observed, “because it looked as though we were having a great deal of fun together, which we were.”

For all the wonderful moments in the filmâincluding scenes with such familiar character actors as Charles Ruggles, Walter Catlett, and Fritz Feldâ

Bringing Up Baby

fizzled at the box office. Some have argued that it came at the tail-end of the “screwball” cycle, when a Depression-weary public was tired of watching silly escapades of the rich. But several classics of the genre, in fact, would appear over the next three years. The awful truth seemed to have been the public's genuine disinterest in the star.

Bringing Up Baby

fizzled at the box office. Some have argued that it came at the tail-end of the “screwball” cycle, when a Depression-weary public was tired of watching silly escapades of the rich. But several classics of the genre, in fact, would appear over the next three years. The awful truth seemed to have been the public's genuine disinterest in the star.

So thought one Harry Brandt, president of the Independent Theatre Owners of America. Speaking on behalf of the hundreds of businessmen whose movie houses were not part of the big studio chains, he published a list of actresses he claimed were “box-office poison”âincluding Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, and Katharine Hepburn. He even posted their names on big one-sheets, which he had pasted around town. Those actresses didn't draw patrons into theaters, Brandt claimed, and he asked the moguls to stop hitching their vehicles to such dim stars.

Nobody at RKO could disagree. Two or three big hits out of fifteen pictures were not enough to warrant greater investment; and Hepburn had already survived five years as a star, the standard run for all but the sacred few. The studio had clearly lost interest in her, offering her an obviously inferior “B” picture called

Mother Carey's Chickens

. Refusing to pull the trigger on her own career, Hepburn bought up the rest of her RKO contract for some $200,000. That her father had been prudently investing her hefty paychecks over the years made her bold move affordable.

Mother Carey's Chickens

. Refusing to pull the trigger on her own career, Hepburn bought up the rest of her RKO contract for some $200,000. That her father had been prudently investing her hefty paychecks over the years made her bold move affordable.

George Cukor stepped in with an offer that even made it desirable. Columbia Studios, the poor cousin to the more established majors, had recently bought a parcel of old scripts from RKO, including the rights to

Holiday

(which had been filmed in 1930 with Ann Harding). Columbia head Harry Cohn hired Cukor to direct the film, figuring they could get Irene Dunne to play Linda Seton, the spunky girl who attracts her socialite sister's impractical fiance. Cukor vigorously argued that the roles were ideal for Hepburn and Grant. Again, Cukor's enthusiasm carried the day. “I knew that Harry Cohn was legendary as the biggest pig in town,” Kate said, “but except for some coarse language, he was never anything but a gentleman with me. More than that, he took a chance on me. He knew how bad my track record had been, and he stuck by me anyway.”

Holiday

(which had been filmed in 1930 with Ann Harding). Columbia head Harry Cohn hired Cukor to direct the film, figuring they could get Irene Dunne to play Linda Seton, the spunky girl who attracts her socialite sister's impractical fiance. Cukor vigorously argued that the roles were ideal for Hepburn and Grant. Again, Cukor's enthusiasm carried the day. “I knew that Harry Cohn was legendary as the biggest pig in town,” Kate said, “but except for some coarse language, he was never anything but a gentleman with me. More than that, he took a chance on me. He knew how bad my track record had been, and he stuck by me anyway.”

Kate thought

Holiday

displayed some of her best acting, and definitely her best work with Cary Grant. After two pictures together, their acting rhythms were in complete synch with one another. And, like their characters, they both found amusement in pretentiousness. “This,” Kate liked to remind me, “was before Cary got too rich, while he still had to work for a living and had fun doing it.” Ten years after she had understudied Hope Williams in the role of Linda Seton, Hepburn made the part indelibly her own, committing to celluloid a performance that is at once moving and comic, complete with her executing double somersaults with Cary Grant. Donald Ogden Stewart, who had acted in the Broadway production, had adapted the play into a fast-clipped scenario; and George Cukor made Hepburn look more glamorous than she ever had before. The film flopped.

Holiday

displayed some of her best acting, and definitely her best work with Cary Grant. After two pictures together, their acting rhythms were in complete synch with one another. And, like their characters, they both found amusement in pretentiousness. “This,” Kate liked to remind me, “was before Cary got too rich, while he still had to work for a living and had fun doing it.” Ten years after she had understudied Hope Williams in the role of Linda Seton, Hepburn made the part indelibly her own, committing to celluloid a performance that is at once moving and comic, complete with her executing double somersaults with Cary Grant. Donald Ogden Stewart, who had acted in the Broadway production, had adapted the play into a fast-clipped scenario; and George Cukor made Hepburn look more glamorous than she ever had before. The film flopped.

The star girded her loins to fight yet another round in Hollywood, when she received a script from MGM with an offer of $10,000âa lower fee than she received when she first landed in Hollywood. She didn't need anyone to tell her it was time to get out of town. In the summer of 1938, Katharine Hepburn retreated to Fenwick with absolutely no prospects for a future in show business.

Â

Â

“I always liked that poem by Robert Frost,” Kate said, referring to

The Death of the Hired Man

â“Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” (It was the only line of poetry I ever heard her recite.) She knew a summer by the sea, with her family and a few select friends, playing tennis and golf, would help her find her bearings. While Hartford was where she came from and New York was where she lived, Fenwick was the place that felt like home, the place she loved most, her family haven for the last twenty-five years.

The Death of the Hired Man

â“Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” (It was the only line of poetry I ever heard her recite.) She knew a summer by the sea, with her family and a few select friends, playing tennis and golf, would help her find her bearings. While Hartford was where she came from and New York was where she lived, Fenwick was the place that felt like home, the place she loved most, her family haven for the last twenty-five years.

Most of the Hartford crowd had left Fenwick by mid-September, but the big wooden Hepburn house, built on brick piles, was more than a summer cottage. Kate intended to stay there indefinitelyâuntil the afternoon of the twenty-first, when a hurricane, which had been threatening the eastern seaboard all week, gusted northward, heading right for the Connecticut River. Kate swam and golfed that morning, but by the afternoon, the waters had turned ferocious, swamping the lawn and pounding against the house. After the chimneys toppled, the windows imploded, and a wing of the house snapped off, Kate, her mother, her brother Dick, and the cook fled to higher ground. They looked back and saw their uprooted house wash out to sea.

“I think,” said Kate looking back on that entire year, “God was trying to tell me something.”

VI

In Bloom Again

I

n 1929 book editor Maxwell Perkins joined Ernest Hemingway in Key West for eight days of fishing. Toward the end of his visit, the editor looked at the panorama of life there in the Gulf Stream and asked his author why he didn't write about it. Just then a big, clumsy bird flew by “I might someday but not yet,” Hemingway said. “Take that pelican. I don't know yet what he is in the scheme of things here.”

n 1929 book editor Maxwell Perkins joined Ernest Hemingway in Key West for eight days of fishing. Toward the end of his visit, the editor looked at the panorama of life there in the Gulf Stream and asked his author why he didn't write about it. Just then a big, clumsy bird flew by “I might someday but not yet,” Hemingway said. “Take that pelican. I don't know yet what he is in the scheme of things here.”

During the ten years I worked on my biography of Samuel Goldwyn, I thought of Katharine Hepburn as my “pelican”âthis unusual creature that was so much a part of the Hollywood landscape but somehow always flapping above it. I used my understanding of her role in the motion-picture community to measure when I was ready to stop researching and begin writing.

She proved to be a good yardstick. Although she never worked with Samuel Goldwyn, her name surfaced practically every day, either in a document or during an interview. In fact, she provided a most pungent comment about Sam and Frances Goldwyn herself, observing, “You always knew where your career in Hollywood stood by where you sat at the Goldwyn table.” For somebody who considered herself a Hollywood outsider, she left lasting impressions there over six decades.

Lucille Ball (who broke in as a “Goldwyn Girl” before attaining costar status in

Stage Door

) remembered Hepburn with adoration and admiration. “We all wanted to be Katharine,” she said, thinking mostly of Kate's self-assuredness. “Even Ginger. No,

especially

Ginger.” Joan Bennett from

Little Women

(who had first worked for Goldwyn as a child in silent pictures) said, “Kate was always the star, there was no mistake about that. But she was always busy giving everybody advice. But it was good advice.” Joseph L. Mankiewicz (who directed

Guys and Dolls

for Goldwyn) was talking about Hollywood's bringing out the best and the worst in people when her name entered the conversation. “You know,” he said, to illustrate his point, “Katharine Hepburn actually spat at me.” As I was wondering whether he was describing the worst being brought out in him or in her, he sheepishly added, “I had it coming.”

Stage Door

) remembered Hepburn with adoration and admiration. “We all wanted to be Katharine,” she said, thinking mostly of Kate's self-assuredness. “Even Ginger. No,

especially

Ginger.” Joan Bennett from

Little Women

(who had first worked for Goldwyn as a child in silent pictures) said, “Kate was always the star, there was no mistake about that. But she was always busy giving everybody advice. But it was good advice.” Joseph L. Mankiewicz (who directed

Guys and Dolls

for Goldwyn) was talking about Hollywood's bringing out the best and the worst in people when her name entered the conversation. “You know,” he said, to illustrate his point, “Katharine Hepburn actually spat at me.” As I was wondering whether he was describing the worst being brought out in him or in her, he sheepishly added, “I had it coming.”

By the time I met Edith Mayer Goetz, she had not spoken to her sister, Irene Selznick, for about a decade. (“We fought over who was top dog, socially, in town,” said Irene dismissively, from which I was to infer that there had been seventy years of sibling rivalry, the causes of which Edie was too superficial to understand.) When I interviewed her, Mrs. Goetz brought up Hepburn's name, bragging how she and Spencer Tracy used to come to her magnificent art-filled house in Holmby Hills. “Oh, the vulgarity,” Irene groaned of the boast when I told her, “and the falsity.” I was surprised myself at the claim, as Kate had told me she and Tracy saw few people as a couple, and the Goetzes were hardly on their social roster.

I asked Mrs. Goetz about their “friendship.” Without missing a beat, Edie produced the guest lists of every one of her fabled parties, and there, indeed, were Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy attending a party for the newlyweds Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow. (“I never really cared for Frank,” Kate later told me, “and you must never ask me about the girl.” I later learned that she considered Mia Farrow's father, an Australian-born writer-director named John, so “depraved” that there was “no way that girl could have any moral structure to her life.”) “But Spence and Frank were friends, and he liked to go out, and so we went to that âwedding party'âin separate cars. But, honestly, I don't remember seeing the inside of the Goetz house more than twice in my life.”) As I was leaving my interview with Mrs. Goetz, her butler (whom, she proudly told me, she had lured from Buckingham Palace) had evidently fallen asleep on the job and was nowhere to be found. My hostess herself walked me to the door, where I had trouble figuring out the unusual handle. “Mrs. Goetz,” I said, after fumbling for a few seconds, “can you help me get this door open?”

“No,” she replied. “Doors have always been opened for me.” (Irene howled about that for years . . . and trotted out the line almost every time I left her apartment.)

Of course, no conversation with George Cukor was complete without some reference to Kate, with whom I think he had more fun than anybody on earth. And yet Kate had always felt she played second fiddle in his life. They worked together nearly a dozen times, he was her landlord for years, and she was the only person licensed to walk into his house unannouncedâwhether it was a weeknight dinner party (“He always seated me below the salt, usually at the very end of the table with Irene Selznick”), Saturday garden parties where, decade after decade, the other great actresses could let down their hair and pick up acting pointers . . . or even the private Sunday pool parties for men only. But Kate knew the leading lady in George's life was Sam Goldwyn's wife, Frances.

As theater novices in upstate New York, they had lived in the same boardinghouses and had become instant friends. Something of an outcast, he found a great admirer in Frances, who appreciated this “angel,” a generous soul who took her under wing and shared his wealth of artistic ideas. For his part, he enjoyed having a Galatea who was such a quick and appreciative study, an icy beauty. Their friendship deepened over the next fifty years, during which time “George's harem,” as Frances Goldwyn often referred to his coterie of famous Hollywood women, widened. Even with Cukor's constant devotion, from the 1930s on, Frances found herself admitting, “I'm really his second favorite. Kate's his first.” In her mind, she invented a rivalry for his affections.

Other books

Mirage by Cook, Kristi

The Rake's Rebellious Lady by Anne Herries

HIS: An Alpha Billionaire Romance (Part One) by Glenna Sinclair

Whose Body by Dorothy L. Sayers

Insecurity and a Bottle of Merlot by Bria Marche

Tales From Sea Glass Inn by Karis Walsh

The Chosen of Anthros by Travis Simmons

Stubborn Love by Wendy Owens

After Dark by Delilah Devlin