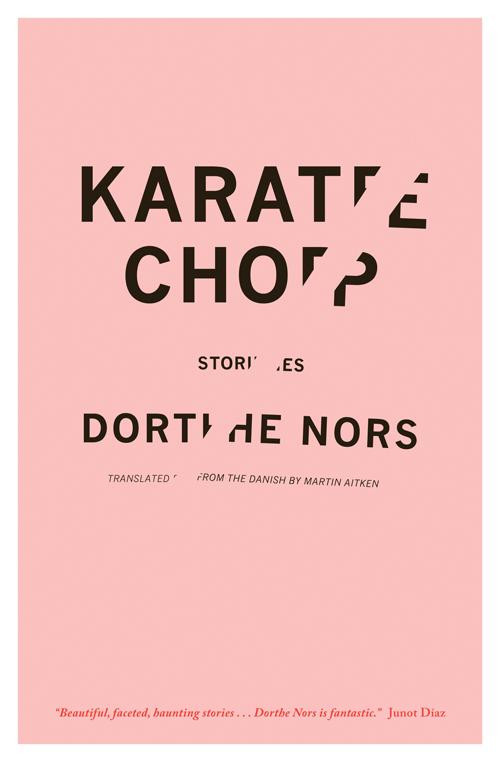

Karate Chop: Stories (Lannan Translation Selection (Graywolf Paperback))

Read Karate Chop: Stories (Lannan Translation Selection (Graywolf Paperback)) Online

Authors: Dorthe Nors

Karate Chop

KARATE CHOP

Stories

Dorthe Nors

Translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken

A Public Space Book

GRAYWOLF PRESS

Copyright © 2008 by Dorthe Nors and Rosinante&Co., Copenhagen. Published by agreement with the Gyldendal Group Agency.

English translation copyright © 2014 by Martin Aitken

Stories from this collection first appeared in earlier forms in the following literary journals: “The Wadden Sea” in

AGNI

; “The Buddhist” in

Boston Review

; “Do You Know Jussi?” in

Ecotone

; “Mutual Destruction” in

FENCE

; “Mother, Grandmother, and Aunt Ellen” in

Guernica

; “Hair Salon” in

Gulf Coast

; “Flight” in

Harper’s

; “Duckling” and “She Frequented Cemeteries” in

New Letters

; “The Heron” in the

New Yorker

; “Female Killers” in the

Normal School

; and “The Winter Garden” and “Karate Chop” in

A Public Space.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, Amazon.com, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

A Lannan Translation Selection

Funding the translation and publication of exceptional literary works

| Supported by a translation grant from the Nordic Council of Ministers |

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-665-1

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-085-7

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2014

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946921

Cover design: Carol Hayes

For my parents

I come from a home with cats and dogs, and those cats were so much on top you wouldn’t believe it. They beat up on the dogs morning, noon, and night. They got beaten up on so much, those dogs, that one year they’d saved up so much hatred they chased one of the neighbor’s cats into a tree with the idea of hanging around until it came down again, after which they ate it.

Contents

MOTHER, GRANDMOTHER, AND AUNT ELLEN

DO YOU KNOW JUSSI?

SHE CAN HEAR THE OTHERS DOWNSTAIRS. JANUS IS STILL THERE too. He has just said good-bye to her up in her room and now he’s saying good-bye to her mother in the doorway. Then everything is quiet again, apart from her older brother turning on the shower across the hall. The smell of meatballs has drifted all the way inside her room and she is lying on the bed with a pillow between her knees. She can still feel the wetness of his saliva just beneath her nose, and his fingers. He made an effort to be nice, that was it, and she turns on the TV. She watches what’s left of the local news, then finds a show where some person looks for someone they knew who has disappeared.

Tonight it’s about a son unable to find his father. The son is thirty, rather chubby, and nearly cries when he says he is not angry with his father. But he can’t understand why his father has not written to him. When the girl whose show it is asks if he’s sad about that, the son can only nod.

A blond journalist Louise remembers once interviewed the prime minister on the television news is seen going through archives and asking people in public offices for information about the son’s missing father. The father’s name is uncommon, Jussi Nielsen, and now the blond journalist is standing outside a redbrick apartment block in a suburb of Copenhagen. He is going to ring the doorbell of an address where someone at the local authority believes Jussi Nielsen may once have lived.

I wonder if anyone’s going to be home

, the journalist says as he rings the doorbell. An elderly woman with a short perm opens the door. She doesn’t look at the camera when she appears, and she doesn’t seem surprised enough when the journalist says he is from national television.

We’re looking for a man called Jussi Nielsen

, says the journalist. The woman opens the door a little bit more and says:

Yes, Jussi used to live here.

The journalist nods.

Do you know Jussi?

he asks.

Yes

, says the woman.

It turns out that the woman, whose face Louise finds plain, was once married to Jussi Nielsen, but they got divorced. The way the apartment is done up, Louise can see they most likely never had much in common. But the journalist doesn’t care about things like that. He wants to know if the woman knows where Jussi Nielsen is now. The woman smiles, and looks straight into the camera. She looks proud:

Yes, I know where Jussi is

, she says.

Louise knows this is not the time to turn off the TV, but she turns it off anyway. Her brother is tramping about in the hall, but otherwise the place is still quiet. Janus hasn’t texted her, but he thought it was a shame it hurt. She looks at the photograph of him by the mirror. He has brown hair and prefers not to smile when his picture is taken. There’s one of Mom and Dad on vacation, too. It seems like a long time ago, and she thinks about Jussi Nielsen and about Janus, who is tall. His fingers are slender and attractive, but he always uses his tongue when he kisses. She finds it odd that he doesn’t use his lips once in a while. Tongue is okay, but it reminds her of the time she and her brother went to work with their dad. They licked envelopes for five kroner an hour at either side of a big, oval desk. Being there was all right, apart from the envelopes. She remembers it because she didn’t care to look at her brother, who wanted to see whose stack of licked envelopes grew the quickest, so she looked down at her work instead. That way she found herself looking too long at the addresses printed on the envelopes.

The letters were all for men and the addresses made her think about people to whom she didn’t belong. She had been able to see them in her mind, going about in strange rooms. She had been able to see them cutting through sports halls, sitting in cars at traffic lights, and walking their bikes and mopeds along the curb. Not just strangers, more like empty sheets of paper waiting to be written on. Or like pausing in front of a butcher’s shop window with your mother and seeing the reflection of a man standing next to you. He looks at the pork sausage. He considers buying the pork sausage, the strange man at the window. Then he decides not to. He turns away, and just before he disappears around the corner he stops and gives you and your mother a strange look.

She had imagined it like that, and she had imagined how she followed the man through the streets all the way to his door, into his stairway and up to the second floor. She went with him inside his apartment and into the kitchen. Here the man made coffee and adjusted the photograph on the counter. Then he went into the living room and turned on the television and watched the news.

She had watched the man as he sat rubbing the armrests with his thumbs. She watched him during the television news, watched him as he ate his pork chops. Later, she was there when he went to the bathroom, and in the ambience of the bedroom when the man put down his magazine on the bedside table and reached out to turn off the light.

There he had lain under his white linen, smelling of duvet, and Louise had wanted to cry. She wanted to shake the man and ask if he had a car. Because if he had a car she wanted him to take her home. She didn’t want to be there anymore. She wanted to go home to her mother, but she couldn’t, because this man, who was nothing but a name on an envelope, had stuck to her, and when later she rang all the doorbells on the stairway to ask if they knew anything about the man who lived on the second floor, they all said they didn’t. His name could have been Olsen, Madsen, Hansen, or Nielsen. No one knew.

“Are you okay? Do you want me to fetch Dad?” her brother had asked that day at their father’s office when they had licked envelopes, and at that moment Louise remembers saying she didn’t care for the adhesive.

“My stomach feels odd,” she said, and then her brother fetched their dad.

But that was then, she thinks to herself, and slides her fingers under her panties to where the skin is thin. It still feels tender, but she thinks it will pass. Her mother is filling the dishwasher, and Dad turns up the volume on the late night news. She mutes the phone and closes her eyes. No word from Janus. That’s a strange name too.