none of the post-López governors had any inclination to challenge their authority. The brush that Villanueva had with the Church was basically over secular matters, and the governor backed down in the clash over Anaya Almazán. Durán de Miranda seems to have been generally pro-Church, and in spite of clashes with his successor, Governor Villanueva, and with the settlers (or at least with the powerful Domínguez family), he was reappointed in the early 1670s following Juan de Medrano y Mesia, of whom relatively little is known. Medrano does seem to have fallen out with the Domínguez faction; at least, according to documents of a later (1685) trial of Juan Domínguez in El Paso, he actually sentenced Juan to death for his bad treatment of Apaches, though the sentence was commuted. Following Durán's second term was Juan Francisco de Trevino, whose use of force against the Pueblos most likely hastened the revolt, something that Trevino left his successor, Antonio de Otermín, to deal with.

|

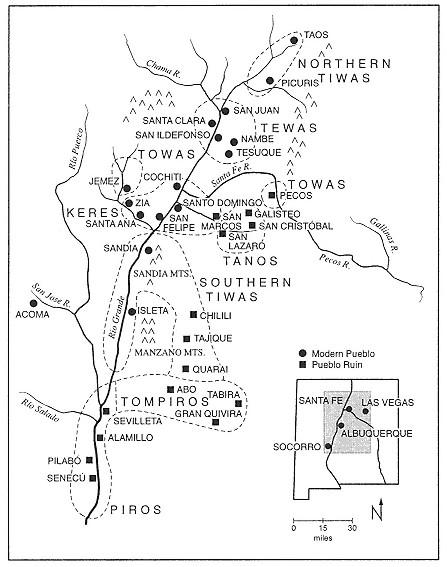

The Medrano y Mesia governorship did coincide with a very grim period in the history of the province. Added to other difficultiesPueblo unrest, pressure from Apachean groups, and continuing dissension within the colony, problems that were becoming more acute by the yearthe period 1667-72 was one of terrible drought and famine conditions throughout New Mexico. In April 1669, the commissary, Juan Bernal, wrote that for the last three years there had been a dramatic shortage of food, with hundreds of Indians dying of hunger (450 at Humanas alone). Not only the Pueblos but the Spaniards were suffering, the latter living primarily on cowhides. Weakened resistance, caused by starvation, may have been a factor in the outbreak of disease, perhaps smallpox, that swept the area in 1671, greatly adding to the turmoil in the province.

|

The famine started with inadequate harvests in the year 1667, which hit the various pueblos very hard. Fortunately, the mission storehouses were stocked with ample supplies of corn, beans, and wheat, and the missionaries had large herds of sheep and cattle. By early 1668 they were beginning to dip into these supplies to alleviate the food shortages among certain of the Rio Grande pueblos. In subsequent years the famine spread to virtually all the pueblos. The Rio Grande itself seems to have been very low in water, perhaps virtually dry, and both Indians and Spaniards who depended on irrigation agriculture suffered greatly.

|

The production of food during those dry years was sporadic. Some pueblos and mission estancias apparently brought in crops, even if somewhat reduced ones, and the same thing was true of the colonists. For example, the wealthy Domínguez de Mendoza family was able to donate cattle for famine relief, as did the Valencia and Garcia families. Other Spaniards were desperate for food. In order to supply the missions and the settlers at Santa Fe, the governors organized the

escolta

, or military escort, to the more exposed areas of the province. Some of

|

|