Kaboom (31 page)

Authors: Matthew Gallagher

An elephant could only pretend to be something else for so long before reality reestablished itself. In our case, a red, white, and blue elephant remembered it preferred trampling to stinging.

On a mid-August afternoon, the Gravediggers and I were conducting a vehicle-maintenance refit back at the FOB when Captain Ten Bears contacted me on the radio regarding a frago.

“We think we have one of our top targets isolated,” he said. “Abu Mustafa, a high-ranking member of a JAM golden group. He's visiting his family in a village in a different troop's area, but he's still our priority because he operates in Saba al-Bor.”

“Roger that, sir.”

“Get the target packet from the squadron intel geeks at the FOB and start planning. The operations staff will let you know when it's time to execute. Also, keep the other troop up-to-date. Coordinate that through the squadron TOC.”

“Roger that, sir.”

My commander laughed. “You got all that, bud? It's a pain in the ass, I know.”

I smirked. “When is it not?”

The mission initially excited me and my platoon. First, any change in our daily monotony felt like a breath of fresh air, as we were far too comfortable with our environment by this point in the deployment. Second, this was legitimate, actionable intelligence, not just information or flimsy hearsay. It seemed too good to be true, and I should have known better. Alas, though, the hope-dope sprung eternal.

I walked from the maintenance bay to the squadron headquarters and collected the target packet. I recognized most of the details of Abu Mustafa's packet from conversations I'd had with various sheiks, Sons of Iraq, and locals. He had worked his way up through an extreme wing of the Mahdi Army from the very bottom, rising from IED emplacer to street thug to street king to bomb maker to financier to network operator. He bounced around constantly, seemingly always on the run, rarely returning home to the village where his wife and children lived. He wielded power by evoking fear and brutally killed other JAM members who did not follow his orders quickly enough or who disagreed with himâwhich, through the process of elimination, also propelled his rise through the ranks. I recalled a muggy night way back in February, when a Son of Iraq informant refused to utter his name

above a whisper, his words drenched in absolute terror. That memory seemed a lifetime away.

above a whisper, his words drenched in absolute terror. That memory seemed a lifetime away.

Bagging this mother fucker might make our month, I thought. And there was always the chance that he was stupid enough to try and fight back with gunfire. . . . The guys would absolutely love that.

I grabbed a map, wrote out my plan, walked over to the TOC, and briefed our new squadron operations officer on the basics. A major, he turned out to be far too grounded, sharp, and fair to deserve the Moe label. I chided myself for yet again stereotyping field-grade officers before I interacted with them.

“Sir, I plan to establish the vehicle cordon here,” I said, pointing at my map. “We'll kick out the dismounts here, moving in two sections, one for clearing the house, the other for inner-perimeter security and support. If all goes well, the target will be detained here.”

“Looks good,” he said and then added a few constructive tweaks. “We'll let the landowners know,” he continued. “Go conduct your rehearsals and stand by for confirmation of the target's location from the intelligence gurus.”

My platoon met me at the staging area, we went over the plan, and we only waited for five minutes before the squadron TOC called on the radio. “White 1, this is Strykehorse X-ray. The target is green. Go ahead and move out, time now.”

“Roger that,” I said and then switched over to our platoon net. “Let's roll!” Our Strykers ripped toward the FOB's gates, as if the sheer act of motion could somehow prevent the inevitable monkey wrench.

I went over the plan one last time on the radio as we moved. “Remember, lock and load as soon as the ramps drop, before you get on the ground. Cordon, keep the crew serve weapons oriented out. Dismounts, slow is smooth, and smooth is fast. We've done this a thousand times. When weâ”

“White 1, White 1, this is Strykehorse X-ray.”

“This is White 1.”

“We need you to turn around and report to the TOC, time now.”

Bamboozled, I asked for clarification. “Say again, over?”

“We need you to turn around and report to the TOC, time now.”

“Uhh, roger, over. I'm halfway out the front gate, heading to that raid you just told me to execute. Perhaps I can take a rain check?”

“Negative, things have . . . changed. Return to the TOC, time now.”

I sighed into the hand mic. “Roger that,” I said, my voice marinated in disgust.

As we pulled back into the staging area on the FOB, the platoon net buzzed.

“Ain't this mutha fucka' a time-sensitive target, sir?” Staff Sergeant Bulldog asked. “Or are we gonna meet him for dinner?”

“Maybe he's not there yet,” I said, pausing. “Maybe. Just stay redcon-1 here guys. I'm sure whatever the holdup is, it won't last long. I'll be right back.”

I ran into the squadron TOC. Some sixty minutes later, I returned.

As I staggered back to my Strykers, I found SFC Big Country, Staff Sergeant Bulldog, and Staff Sergeant Boondock smoking cigarettes on the front side of the lead vehicle.

“Well?” they asked simultaneously.

“Well,” I sighed. “Well. There was some . . . debate between some captains and some majors as to who should execute this mission. We were originally tapped to go because we were available and on the FOB, and the squadron operations officer wanted speed.”

“That makes sense,” SFC Big Country said.

“That it does,” I replied. I needed to be more forthcoming about what had happened with these three, I thought. They deserved it. “Not everyone agreed. To make a long story short, Lieutenant Colonel Larry got involved, and while we're still doing the raid, we're now under the landowner's command for it.”

“Jesus fucking Christ, you're telling me some invisible lines on a fucking map and a bunch of territorial officers bitching at each other did this?” Staff Sergeant Boondock fumed. “This is bona fide bureaucratic bullshit, sir. This dude is high level, and like Bulldog said, it's a time-sensitive mission! What the fuck are they thinking? This isn't some goddamn cowboy movie where the bad guy waits for us at a corral.”

I nodded. “I hear you. But our time is not our own to manage anymore. We anticipated rather than reacted. Lesson learned.” I smirked. “Now the four of us, we have to go meet up with the landowning commander. He's going to brief us on his plan.”

I found the landowning captain's plan a solid one, though more complex than mine, certainly, as it had more moving parts and involved units that had never worked together before. Whereas my plan aimed for crashing lightning, in and out just long enough to nab Abu Mustafa, this aspired for rolling thunder, a methodical cordon with a very clear step-by-step process. Admittedly, his brief was better than mine; I found it very smooth and thorough, and it lacked my infamous crutch phrases, like “fuckin'” or “you know?” Further, he had color maps, which contained all sorts of coolâif irrelevantâ

demographic breakdowns in pie chart form. Even disgruntled, I still appreciated shiny things.

demographic breakdowns in pie chart form. Even disgruntled, I still appreciated shiny things.

Some two and a half hours after we got the initial confirmation of Abu Mustafa's whereabouts, we finally kicked open the front door to his house. No one was home, although we found food in the pantry and a few other signs of recent habitation.

“Guess we was late for dinner,” Staff Sergeant Bulldog said as we moved back to our Strykers after clearing the house.

Various possibilities for the mission's failure swept through my mind. Maybe the presence of so many Coalition forces tipped Abu Mustafa off; anything larger than a roving platoon stuck out as out of the ordinary for any village in this part of Iraq. Maybe he had guards posted on the outside of town and fled at the first sign of Americans. Or maybe we just took too fucking long. Whatever the case, Abu Mustafa had escaped and, as far as I knew, wouldn't be found at any point during our deployment.

The recentralization movement continued. In the ensuing months, Higher developed an obsession with quantifying every aspect of the war effort. PowerPoint slides and pie charts and information overload for the sake of information overload then became our raison d'êtreâthe more of those things we did, the more we were left alone to conduct legitimate counterinsurgency operations the way we knew how. The mass quantifying reached a personal apex when I tracked “nose time,” the number of minutes a military dog spent sniffing for explosives over the course of a mission.

We certainly were no swarm of killer bees. As I looked back on the experience though, I liked to believe that if nothing else, we made our elephant cut some of its excess lumbering weight. That was something, at least.

That was the war I fought.

MERRY MEN AND MICROGRANTS“Why the hell are we doing

this again?” Staff Sergeant Axel (recently promoted) asked.

this again?” Staff Sergeant Axel (recently promoted) asked.

“So our squadron's microgrant bar graph on the brigade PowerPoint slide can be the highest,” Staff Sergeant Spade answered offhandedly. “Don't worry, it's all good. We're about halfway done. If we keep the same pace, we'll be done, in what, another four, five hours?”

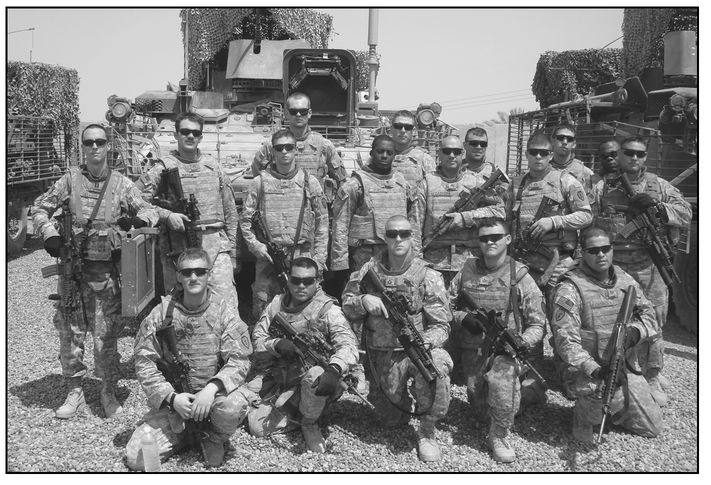

The Gravediggers, 2nd platoon of Bravo Troop, 2-14 Cavalry, circa August 2008, at combat outpost Bassam. Front row, from left to right: Corporal Spot, Doc, PFC Stove Top, PFC Smitty, PFC Romeo. Middle row, from left to right: myself, Staff Sergeant Boondock, Sergeant Tunnel, Specialist Haitian Sensation, Sergeant Fuego, Staff Sergeant Axel, PFC Van Wilder. Back row, from left to right: PFC Das Boot, SFC Big Country, Sergeant Prime, Staff Sergeant Spade, and Staff Sergeant Bulldog.

I didn't bother correcting my NCOs, as I silently agreed with their cynical assessment of our mission's purpose. The Gravediggers and I had spent our entire sunny morning on Route Maples, writing down local businesses' contact information, and we were bound to spend our entire sunny afternoon the same way. The microgrant program had developed in and with the American military's COIN efforts; in theory, it supplied local Iraqi-owned businesses with a small sum (generally US$300 to US$500) for specific refinements to aid their commerce. These businesses were supposed to be vetted beforehand for any shady connections, and their refinement purchases were supposed to be verified by American units after the issuing of the micrograntâagain, all in theory. In practice, the microgrant program devolved into another quantifiable figure that unit commanders used to compete for officer evaluation report (OER) bullets. So, when Captain Ten Bears got the order to devote his entire troop to mass microgrant projects in Saba al-Bor over the course

of three days, I knew we weren't meeting the program's intent. But other than a sarcastic comment or two to my peers, I shut up and executed. I wasn't walking the pariah road again.

of three days, I knew we weren't meeting the program's intent. But other than a sarcastic comment or two to my peers, I shut up and executed. I wasn't walking the pariah road again.

My platoon's slice of this mission proved the smallest in area but held the largest number of businesses. Approximately two miles long, Route Maples served as Saba al-Bor's main strip as nearly every building, shanty, and tarp on both the east and west sides of the cluttered street contained a business of some kind. Later that night, as I organized our mission's collection efforts, I totaled 532 local businesses on Route Maples.

“Dude, I feel so dirty doing this!” Skerk yelled over to me, both of us jotting down names, type of business, and phone numbers supplied by the owners. “It's one thing to witness a scam like this, but it's a whole other thing to be the one peddling it!”

As our troop's artillery and contracts officer, Skerk oversaw the microgrant program in our AO. For the first few months of our deployment, he used its funds the way we had been taught toâprecisely targeting specific businesses that supported the efforts of Coalition forces, helping them out with a new freezer or upgraded furniture, and allowing news of the benefits of working with us to spread through the populace by word of mouth. Obviously, that was before the microgrant program came onto Higher's radar. Now, Skerk served as the ringmaster in a circus of mass microgrant issuing. We often joked about which specific American taxpayer had paid for the random object deemed “vital to commerce” by an Iraqi business owner, but it was only funny because the concept of money meant nothing to us anymore.

While I listened to a young Iraqi grocery shop owner explain to me why he wanted to use his pending microgrant on a foosball table, I thought about how unenforceable all of this was. We couldn't take back a grant after the fact, whether the Iraqis bought something pragmatic or not. And while our guidance for dealing with this problem had us telling transgressors that we had added them to our terrorist watch list, we could only issue the threat so many times before it became an Arabic punch line.

Other books

Unknown by Unknown

Extraordinary Losers 3 by Jessica Alejandro

Catching Eagle's Eye by Samantha Cayto

Dead Simple by Jon Land

The Beautiful Between by Alyssa B. Sheinmel

La Odisea by Homero

Shooting Butterflies by Marika Cobbold

Secrets of Moth (The Moth Saga, Book 3) by Arenson, Daniel

The Wolf's Pursuit by Rachel Van Dyken

To love and to honor by Loring, Emilie Baker