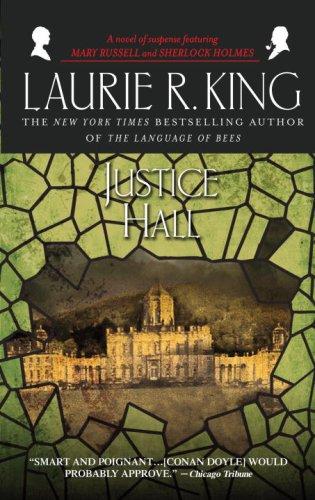

Justice Hall

Authors: Laurie R. King

Tags: #Women detectives, #Married women, #England, #Historical Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Country homes, #General, #Women detectives - England, #Mystery Fiction, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Russell; Mary (Fictitious character), #Holmes; Sherlock (Fictitious character), #Traditional British, #Fiction

Only hours after Holmes and Russell return from solving one murky riddle on the moor, another knocks on their front door…literally. It’s a mystery that begins during the Great War, when Gabriel Hughenfort died amidst scandalous rumors that have haunted the family ever since. But it’s not until Holmes and Russell arrive at Justice Hall, a home of unearthly perfection set in a garden modeled on Paradise, that they fully understand the irony echoed in the family motto, Justicia fortitudo mea est:

A trail of ominous clues comprise a mystery that leads from an English hamlet to the city of Paris to the wild prairie of the New World. The trap is set, the game is afoot; but can Holmes and Russell catch an elusive killer—or has the murderer caught them?

A Novel by

Laurie R. King

Laurie R. King

Mary Russell Series

Copyright © 2002

by Laurie R. King

(YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE)

Familia fortitudo mea est.

LET JUSTICE ROLL DOWN LIKE THE WATERS,

AND RIGHTEOUSNESS LIKE AN

EVERFLOWING STREAM.

—Amos 5:24

This volume is the sixth chapter in the chronicles of Mary Russell and her partner, the near-mythic (even, it would seem, in the 1920s) Sherlock Holmes. It comes chronologically after their 1923 adventure described in

The Moor,

but is linked with the characters from

O Jerusalem,

which took place in 1919.

I, Miss Russell’s literary agent and editor, had a certain amount of assistance in the preparation of this book, people who assisted in the task of ensuring that Miss Russell’s narrative did not stray too far from the path of historical truth. Ms Anabel Scott helped this poor Colonial to sort out the rules, regs, and terminology regarding the British aristocracy. Ms Tara Lengsfelder uncovered the paper written by Miss Russell on the boat to New York, running it to earth in an obscure American university journal from the spring of 1924. Mr Stuart Bennett, antiquarian bookseller extraordinaire, confirmed the titles of the books in the Justice Hall library.

Thanks to them all, and to nameless others, not the least of whom was the kind and anonymous soul who sent me Miss Russell’s manuscripts in the first place, for the benefit, and the puzzlement, of all.

LAURIE R. KING

Home, my soul sighed. I stood on the worn flagstones and breathed in the many and varied fragrances of the old flint-walled cottage: Fresh beeswax and lavender told me that Mrs Hudson had indulged in an orgy of housecleaning in the freedom of our prolonged absence; the smoke from the wood fire seemed cleaner than the heavy peat-tinged air I’d been inhaling in recent weeks; the month-old pipe tobacco was a ghost of its usual self; and beneath it all the faint, dangerous, seductive tang of chemicals from the laboratory overhead.

And scones.

Holmes grumbled his way past, jostling me from my reverie. I stepped back out into the crisp, sea-scented afternoon to thank my farm manager, Patrick, for meeting us at the station, but he was already away down the drive, so I closed the heavy door, slid its two-hundred-year-old bolt, and leant my back against the wood with all the mingled relief and determination of a feudal lord shutting out an unruly mob.

Domus,

my mind offered.

Familia,

my heart replied. Home.

“Mrs Hudson!” Holmes shouted from the main room. “We’re home.” His unnecessary declaration (she knew we were coming; else why the fresh baking?) was accompanied by the characteristic thumps and cracks of possessions being shed onto any convenient surface, freshly polished or not. At the sound of her voice answering from the kitchen, I had to smile. How many times had I returned here, to that ritual exchange? Dozens: following an absence of two days in London when the only things shed were furled umbrella and silk hat, or after three months in Europe when two burly men had helped to haul inside our equipage, consisting of a trunk filled with mud-caked climbing equipment, three crates of costumes, many arcane and ancient volumes of worldly wisdom, and two-thirds of a motor-cycle.

The only time I had come to this house with less than joy was the day when Holmes and my nineteen-year-old self had been acting out a play of alienation, and I could see in his haggard features the toll it was taking on him. Other than that time, to enter the house was to feel the touch of comforting hands. Home.

I caught up my discarded rucksack and followed Holmes through to the fire; to tea, and buttered scones, and welcome.

Hot tea and scalding baths, conversations with Mrs Hudson, and the accumulated post carried us to dinner: urgent enquiries from my solicitor regarding a property sale in California; a cheerful letter from Holmes’ old comrade-at-arms, Dr Watson, currently on holiday in Egypt; a demand from Scotland Yard for pieces of evidence in regard to a case over the summer. Over the dinner table, however, the momentum of normality came to its peak over Mrs Hudson’s fiery curry, faltered with the apple tart, and then receded, leaving us washed up in our chairs before the fire, listening to the silence.

I sighed to myself. Each time, I managed to forget this phase—or not forget, exactly, just to hope the interim would be longer, the transition less of a jolt. Instead, the drear aftermath of a case came down with all the gentleness of a collapsing wall.

One would think that, following several taut, urgent weeks of considerable physical discomfort on Dartmoor, a person would sink into the undemanding Downland quiet with a bone-deep pleasure, wrapping indolence around her like a fur coat, welcoming a period of blank inertia, the gears of the mind allowed to move slowly, if at all. One would think.

Instead of which, every time we had come away from a case there had followed a period of bleak, hungry restlessness, characterised by shortness of temper, an inability to settle to a task, and the need for distraction—for which long, difficult walks or hard physical labour, experience taught me, were the only relief. And now, following not one but two, back-to-back cases, with the client of the summer’s case long dead and that of the autumn now taken to his Dartmoor deathbed, this looked to be a grim time indeed. To this point, the worst such dark mood that I had experienced was that same joyless period just under five years before, when I was nineteen and we had returned from two months of glorious, exhilarating freedom wandering Palestine under the unwilling tutelage of a pair of infuriating Arabs, Ali and Mahmoud Hazr, only to return to an English winter, a foe after our skins, and a necessary pretence of emotional divorcement from Holmes. I am no potential suicide, but I will say that acting one at the time would not have proved difficult.

Hard work, as I say, helped; intense experiences helped, too: scalding baths, swims through an icy sea, spicy food (such as the curry Mrs Hudson had given us: How well she knew Holmes!), bright colours. My skin still tingled from the hot water, and I had donned a robe of brilliant crimson, but the coffee in my cup was suddenly insipid. I jumped up and went into the kitchen, coming back ten minutes later with two cups of steaming hot sludge that had caused Mrs Hudson to look askance, although she had said nothing. I put one cup beside Holmes’ brandy glass and settled down on a cushion in front of the fire with the other, wrapping both hands around it and breathing in the powerful fragrance.

“What do you call this?” Holmes asked sharply.

“A weak imitation of Arab coffee,” I told him. “Although I think Mahmoud used cardamom, and the closest Mrs Hudson had was cinnamon.”

He raised a thoughtful eyebrow at me, peered dubiously into the murky depths of the cup, and sipped tentatively. It was not the real thing, but it was strong and vivid on the palate, and for a moment the good English oak beams over our heads were replaced by the ghost of a goat’s-hair tent, and the murmur of the flames seemed to hold the ebb and flow of a foreign tongue. New flavours, new dangers, and the sun of an ancient land, the land of my people; trials and a time of great personal discovery; our Bedu companions, Mahmoud the rock and Ali the flame. Odd, I thought, how the taciturn older brother had possessed such a subtle hand at the cook-fire, and had made such an art of the coffee ritual.

No, the dark substance in our cups was by no means the real thing, but both of us drank to the dregs, while images from the weeks in Palestine flickered through the edges of my mind: dawn over the Holy City and mid-night in its labyrinthine bazaar; the ancient stones of the Western Wall and the great cavern quarry undermining the city’s northern quarter; Ali polishing the dust from his scarlet Egyptian boots; Mahmoud’s odd, slow smile of approval; Holmes’ bloody back when we rescued him from his tormentor; General Allenby and the well-suited Bentwiches and the fair head of T. E. Lawrence, and—and then Holmes rattled his newspaper and the images vanished. I fluffed my fingers through my drying hair and picked up my book. Silence reigned, but for the crackle of logs and the turn of pages. After a few minutes, I chuckled involuntarily. Holmes looked up, startled.

“What on earth are you reading?” he demanded.

“It’s not the book, Holmes, it’s the situation. All you need is an aged retriever lying across your slippers, we’d be a portrait of family life. The artist could call it

After a Long Day;

he’d sell hundreds of copies.”

“We’ve had a fair number of long days,” he noted, although without complaint. “And I was just reflecting how very pleasant it was, to be without demands. For a short time,” he added, as aware as I that the respite would be brief between easy fatigue and the onset of bleak boredom. I smiled at him.

“It is nice, Holmes, I agree.”

“I find myself particularly enjoying the delusory and fleeting impression that my wife spends any time at all seated at the feet of her husband. One might almost be led to think of the word ‘subservient,’?” he added, “seeing your position at the moment.”