Jungle of Snakes (20 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

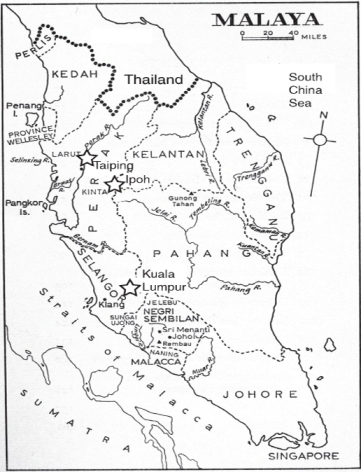

A Winning Strategy

By British standards, Templer commanded a sizable force including half of the line regiments in the entire British army, all

its Gurkha battalions, and a variety of regiments from the remnants of the far-flung empire, including the King’s African

Rifles and the Fijian Regiment. He intended to wield them differently, moving away from large sweeps and instead concentrating

on keeping units in one area long enough so they could learn the local terrain. Templer also thought that various British

units had acquired valuable experience in jungle fighting and that this knowledge needed to be collected and disseminated

in a systematic way. The result was a booklet entitled “The Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya.” Based on the

syllabus of the Jungle Warfare Training Centre, it was written in just two weeks. It was a practical how-to compendium describing

techniques for patrolling, conducting searches, setting ambushes, and acquiring intelligence. Printed in a size that fit into

a jungle uniform pocket, “The Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya,” inevitably given the acronym ATOM, served as

a soldier’s bible. Templer inscribed his own copy with this notation: “It is largely as a result of the publication of this

handbook . . . that we got militant communism in Malaya by the throat.”

10

The improvement in jungle tactics coincided with the insight that the vast, apparently impenetrable jungle actually held a

limited network of trails and that the enemy had no choice but to use them. Communist couriers, food requisition parties,

and organized units carrying out operations had to traverse these trails some time or another. Rather than noisily bashing

about the jungle on useless large-scale sweeps, the British tactic of choice became the setting of an ambush overlooking a

trail, followed by a patient waiting period. Platoons operated along the jungle edge for ten to twenty days at a time. They

spent most of their time watching and listening.

For a superior officer, the notion of passively waiting for the enemy to appear flew in the face of conventional training.

For the soldiers waiting silently hour after hour trying to ignore the leeches, mosquitoes, sleep-inducing heat and humidity,

and fatigue, it was not pleasant. A British officer wrote, “I had grown used to the jungle during the war in Burma, but there

we were always in large parties and in touch either by sound or wireless with the units to our left and right. Also we always

had some idea of where the enemy was. Here we were just a little party of ten men, completely isolated, and the enemy was

God knows where. He might be behind the next bush, or the one beyond that, or he might be a hundred miles away. We never knew.”

11

Most of the time no one passed the ambush site. Yet statistics revealed that on average a soldier on patrol encountered an

insurgent once every 1,000 hours. The same soldier waiting patiently in ambush saw an insurgent once every 300 hours. Typically,

a contact did not occur until after the ambushers had been in position for more than twenty-four hours. An officer tabulated

his accomplishments at the end of his tour. He had spent 115 days in the jungle: “I was with my company when we shot and killed

a terrorist. I set an ambush with a section of my platoon which shot and killed a terrorist. My platoon shot and killed a

terrorist in an ambush while I was on leave. A company operation in which I took part resulted in four terrorists surrendering.

I fired at, but missed, a terrorist who was running away from a camp which we were attacking.”

12

Based on conversations with fellow officers, he concluded that he had experienced a fairly active tour of duty.

Jungle ambush was not comfortable, it was not glorious, but in this war it was the most effective purely military tactic.

Food Denial

The Malayan jungle did not produce enough food to sustain the guerrillas. They needed to obtain sustenance from sympathizers

living outside the jungle to survive. The British knew this and conceived a strict food denial program (what became known

as Operation Starvation) to starve the guerrillas. Weakened by hunger, they would become vulnerable to military operations

or surrender. The food denial strategy proved a devastating measure that eventually defeated the insurgents.

The British carefully followed a three-phase approach to implement the food denial strategy. A months-long intelligence-gathering

operation inaugurated the program. Special Branch officers infiltrated the Min Yuen support organization inside a designated

village. During this time, military patrols deliberately avoided this village. Instead, they operated in adjacent areas in

the hope that their presence would push the terrorists toward the apparent sanctuary of the designated village.

The second phase began the day the strict food rationing began and lasted three to five months. It included house-to-house

searches to seize food stores and the arrest of known Communist agents who had been identified by the Special Branch undercover

agents. Thereafter, security forces tightly guarded the supply convoys that delivered rice to the village. The rice was cooked

centrally by government cooks while armed guards looked on. Within the village, authorities controlled the sale and distribution

of all other food. Meanwhile, the military patrolled the nearby jungle to provide security against insurgent attacks.

The people were told that the restrictions would end as soon as the terrorists had been killed or captured. If all proceeded

as planned, the villagers would tire of this intrusive disruption and denounce the Communist infrastructure. Then, in the

final phase, Communist turncoats would lead Special Branch operational teams, masquerading as Communist terrorists, against

higher-level formations.

THE FOOD DENIAL effort was not airtight. At first many of the village perimeters lacked illumination, making it easy for Communist

sympathizers to throw food and medicine to the waiting guerrillas outside the wire. As perimeter security improved, the sympathizers

turned to other tactics. Villagers smuggled rice by hiding it inside bicycle frames, cigarette tins, or false-bottomed buckets

of pig swill on the supposition that a Malay policeman, because of his Muslim religion, would be unwilling to touch anything

to do with swine. When security forces detected these dodges, the insurgents increasingly turned to using children to smuggle

food.

The soldiers and the police usually harnessed their efforts in tandem. An infantry officer wrote, “The police could not take

on the fighting against the bandits in the jungle, whereas we could not undertake the normal process of maintaining law and

order in the villages and towns and protected areas.”

13

Another infantry officer inspected his men while they were on gate duty at a New Village. Long lines of pedestrians, cyclists,

and vehicles impatiently waited to leave the village while hour after hour the men of the South Wales Borderers performed

meticulous vehicle and body searches. He wrote, “It is not easy to turn one’s battalion into a cross between a body of high-class

customs officials and police detectives, but what I saw that morning confirmed everything that has been said about the adaptability

of the British soldiers.”

14

As the security forces became ever more serious about enforcing food regulations, which meant time-consuming personal body

searches each morning, villagers became understandably more angry about the long lines as they went outside the wire to work

in the fields and jungle. Communist propagandists tried to magnify village grievances, claiming security forces were taking

indecent advantage of females during searches. Although the international press published some of this propaganda, it failed

to deter the British from intensifying their food denial efforts.

The mere possession of food outside the wire risked a penalty of up to five years in prison. The government reduced the number

of stores authorized to sell food, banned tinned Quaker Oats because it was an insurgent emergency ration, restricted the

sale of high-energy foods and medicines, and ordered shop keepers to puncture tins of food in the presence of the buyer so

tropical heat could begin its spoiling process and prevent the food from being stockpiled for the insurgents. Other draconian

measures severely restricted the quantities of tinned meat, fish, and cooking oil permitted in individual households.

While the New Villages were subjected to the methodical imposition of food denial measures, military search-and-destroy operations

in adjacent areas proceeded. Often during these operations the security forces imposed a severe rice ration on the local inhabitants.

Government spokesmen claimed that this ration was “just enough to keep a person in good health.” According to the Chinese

Chamber of Commerce this was not true. The rice ration created “fifty thousand half-starved people, many of whom were too

ill or to weak to work.”

15

Templer and his subordinates were not blind to the human suffering caused by the food denial program. They also considered

other adverse consequences such as the real risk of spawning a repressive governmental bureaucracy and the impact of international

opprobrium. They weighed the operational effect of the food denial policies versus the impact on civilian morale and pressed

ahead. At the same time, the British offered the people an enormous incentive to cooperate. The British called this inducement

the “White Area,” a symbolic cleansing of the red taint of Communism.

White Areas were almost literally the carrot to the stick of Emergency regulations. When a region demonstrated loyalty to

the government and a corresponding dramatic reduction in Communist activity, authorities suspended Emergency regulations including

most especially food restrictions, curfews, limited business hours, and controls over the movement of people and goods. The

inhabitants of the New Villages still had to live within their assigned villages and maintain their defenses. But compared

to their onerous life under Emergency regulations, this was freedom. The government declared the first White Area in September

1953 and during the next two and a half years extended this designation to include almost half the country’s population.

AS TIME PASSED, the operational effects of the food denial program were dramatic. The guerrillas literally began to starve.

They could hardly lean on sympathizers to provide for them since those sympathizers could honestly say that strict rationing,

central cooking, thorough gate searches, and swarming security patrols prevented them from smuggling food to the guerrillas.

When British intelligence pinpointed a guerrilla band on the verge of starvation, security forces flooded the area and food

denial operations intensified. At such times civil life came to a standstill as the security forces imposed curfews of up

to thirty-six hours along with very strict rice rationing. Knowing that the guerrillas would have to move or die, military

forces flooded the area to set ambushes along every possible trail. One such operation in Johore featured three infantry battalions,

five Area Security Units, two Police Special service Groups, and a “volunteer” force of ex-guerrillas. For five weeks these

forces operated in conjunction with strict local food denial and pervasive psychological warfare efforts. They never killed

a single guerrilla, yet their presence led to the collapse of guerrilla morale. Hobbled by hunger, compelled to keep on the

move while dodging patrols and ambushes, the guerrillas initially survived only by operating in ever-smaller groups. This

dispersal led to the breakdown of command authority. In the absence of officers, individuals found it easier to surrender.

As unit disintegration continued, the leaders concluded that further resistance was futile and they too surrendered.

This type of operation could only work in compact, carefully targeted areas where the security forces could completely dominate

the terrain. The Johore operation required an enormous expenditure of effort to capture one guerrilla and receive the surrender

of eleven more. However, it was an operational approach to which the guerrillas had no answer.

The Battle for Intelligence

THROUGHOUT HIS TENURE IN command Templer emphasized the paramount importance of intelligence. “Malaya is an Intelligence war,”

he repeatedly asserted.

1

In the absence of good intelligence, jungle patrolling, no matter how professionally carried out, failed to produce results.

As one officer noted, “No intelligence meant no contacts and no contacts meant no intelligence.”

2

In theory, the police were in the best position to provide useful intelligence. However, until Templer set in train comprehensive

reforms, both police and military intelligence were often inaccurate or useless. A British officer, John Chynoweth, served

with the Malay Regiment. He received a top-secret debriefing of an informer and used the information to plan a patrol. The

result was “the most colossal mess-up of an operation ever.”

3

Only a last-second instinct for restraint prevented Chynoweth from accidently killing innocent villagers. He pondered what

had gone wrong and speculated that the informer might have deliberately denounced the villagers as part of an ongoing personal

feud, might have made a genuine mistake, or might have simply hoped that the patrol would somehow encounter a terrorist and

then he would “earn” his reward. After another eight-day sweep that failed to find the enemy, Chynoweth wrote in June 1953,

“I’m sure this is not the way to get them. We are not fighting an army, but small groups who do not fight pitched battles

. . . Bandits can move many times faster than any of our platoons, are clever and desperate and elusive. The best way is to

get information from villages or surrendered bandits who lead one to a definite camp.”

4

In a conflict where intelligence was king, very little useful intelligence came from the Chinese villages until the government

established secure police posts within the villages. These police stations then became the hub for security and intelligence.

The local police knew who should and who should not be present in a village. Their ability to distinguish residents from outsiders

severely curtailed Communist movement. When the police arrested a Communist sympathizer, or better still an agent or courier,

he or she might divulge useful information allowing the security forces to roll up an entire Communist cell.

As part of their counterinsurgency philosophy that emphasized acting within legal boundaries, the British worked hard to improve

the police. Great Britain had considerable experience in handing over colonial authority to the native people. Part of this

process was to train the police. To help in Malaya, the British summoned experienced trainers from around the Empire including

hundreds of former police sergeants who had served in Palestine. In January 1952 Colonel Arthur Long, commissioner of the

City of London Police, came to Malaya to reorganize the Federation Police and Special Constables. Within a year the Federation

Police had compiled comprehensive lists of Malayan Races Liberation Army personnel and documented the local areas where they

operated. Armed with this specific and precise intelligence, small hunter-killer platoons went after the guerrillas.

In contrast to the regular army units who had bashed through the jungle, the hunter-killer platoons were well-trained units

composed of soldiers who had learned how to operate in the jungle. They were superbly fit in order to operate in the enervating

environment, and first-class marksmen. Their sharpshooting skill was important because shoulder-fired weapons remained the

weapon that inflicted almost all casualties on the enemy. The combination of jungle stamina, fire discipline, knowledge of

the country, and high morale made the men of the hunter-killer platoons implacable foes of the guerrillas. Yet even when nourished

with good intelligence, these platoons still spent hundreds of hours of fruitless searching in order to locate the insurgents.

Then, when contact came, it was fleeting, and “bags” seldom exceeded two or three guerrillas killed.

Another tool in the war for intelligence was a national registration program. Introduced early in the Emergency, it required

every person over the age of twelve to register at the police station to obtain an identity card complete with photo and thumbprint.

Thereafter, they always had to carry this card with them while the police retained a copy. To make the system work the government

had to provide a strong incentive. It chose coercion. People needed to show their cards to obtain a food ration, to build

a home in a resettlement village, to expand their garden plot, and for a host of other daily activities tied to economic survival.

Naturally the civilian population resented all of this but they quickly appreciated that life was easier with rather than

without their cards.

From a security viewpoint, the program was a great success. Registration hampered all Communist movement and activity. But

it was particularly effective in the New Villages, where it helped separate the insurgents from the local populace. In the

New Villages, police established cordons early each morning to screen people as they embarked on their daily routines. The

police detained anyone without a card or whose card showed that they were not local. People who did not appear for work that

day immediately attracted police attention and became the subjects of closer investigation.

Chin Peng and the Communist leadership correctly saw that the registration program was a serious threat and ordered the Traitor

Killing Squads into action. They assassinated the village photographers and registration officials who worked in the program.

The also targeted the rural rubber tappers and rice farmers. Guerrillas seized their registration cards and threatened to

kill them if they reregistered. The police responded with a simple policy change. Each morning they collected workers’ cards

and issued tallies when they left the village. Upon returning, workers exchanged the tallies for the cards. If the guerrillas

had stolen the tally, the worker merely had to reregister. Guerrilla leaders eventually concluded that their efforts to disrupt

the program were counterproductive and abandoned this campaign as part of their strategic reappraisal conducted in October

1951.

Early in the conflict, the British had also begun a reward program whereby they paid set sums for weapons and munitions surrendered

to the security forces and offered a higher inducement for leading a patrol to a guerrilla base. Under Templer’s leadership

the British raised the bounty for killing or capturing Communist insurgents. The largest bounty was placed on the head of

Chin Ping: 250,000 Malayan dollars (£30,000, approximately $83,700) if delivered alive, half that amount if killed. Either

sum was a staggering figure for Malaya. At the time the offer of oversized rewards caused some criticism. Police and government

officials wondered about the justice system’s essential fairness whereby a known murderer, a man who had targeted policemen

and rural administrators, could receive a sum for a few minutes of work betraying his comrades that far exceeded what a loyal

man could ever earn during a lifetime of faithful service.

The commander of the Malayan Races Liberation Army in southern Malaya, Ah Koek, known as “Shorty,” had a price tag of 150,000

Malayan dollars if taken alive or 75,000 if killed. In October 1952 his bodyguard murdered him and delivered his head to obtain

the reward. A newspaper reporter gleefully observed that since Ah Koek was only four feet nine inches tall, this came to almost

$3,000 an inch, probably the most expensive “head price” ever paid. The elimination of a well-known insurgent leader boosted

British morale but had little collateral benefit since most of these men could be readily replaced. More useful than the bounty

was the reward system for actionable intelligence.

Security force officers were constantly surprised at the willingness of Communist turncoats to guide them to their old positions

to kill or capture their former comrades. In part this was a monetary calculation on the turncoat’s part: he received a bounty

to surrender and could collect more by leading productive raids. In part it was a calculus of survival: a turncoat had to

fear the notorious Traitor Killing Squads, which would target the turncoat’s family if they could not eliminate the betrayer

himself. The turncoat judged the best way to preempt retaliation was to kill his comrades before they could pass on information

to these death squads.

End Game

In late spring 1954 Templer left Malaya. In his mind much remained to accomplish. As he departed he famously warned against

complacency, saying, “I’ll shoot the bastard who says that this Emergency is over.”

5

Then and thereafter, Templer was a controversial figure. His brusque, even rude personality did not win him many friends.

Detractors claimed that he merely happened to be the man in charge when the tide turned. Indeed, he did benefit greatly from

decisions made by his predecessors. Still, by any objective measure his success had been extraordinary. In 1951, the year

prior to his arrival, insurgents had staged 2,333 major incidents while inflicting more than 1,000 casualties among the security

forces and another 1,000 against civilians. In 1954 there were 293 major incidents causing 241 security force and 185 civilian

casualties. Guerrilla strength had declined by two thirds from its peak.

Templer had also promoted the expansion of the popular militia called the Home Guard. It was an ambitious effort fraught with

risk, the fruits of which were not apparent until after Templer had left Malaya. Trained by British and Commonwealth officers,

the Home Guard grew from 79,000 in July 1951 to 250,000 by the end of 1953, at which time they defended seventy-two New Villages.

A typical village had thirty-five Home Guards. Assignments rotated among them on a daily basis, so on any one night only five

were on guard duty. At nightfall, the guards drew weapons from the police armory and patrolled the perimeter wire. Their tasks

were threefold: to detect and resist guerrilla attack, to thwart the internal activity of the Traitor Killing Squads, and

to prevent the villagers from smuggling food outside the wire. Although subjected to terrorist intimidation and murder, the

Home Guard maintained a surprising resilience. By the end of 1954 they had received 89,000 weapons and lost only 103. In 1955

they lost 138 weapons out of a holding of 15,000. Still, even this record was unsatisfactory to some Europeans in Malaya who

loudly demanded the Home Guard be disbanded.

Authorities ignored the complaints. It became clear that the degree of loyalty to the government exhibited by the Home Guard

mirrored the attitudes of the villagers. If Communist terror had cowed the villagers, the Home Guard was passive for fear

of Communist reprisal against themselves and their families. When later there was a major guerrilla attack against two New

Villages in Johore in 1956, the Home Guard defended the villages tenaciously—in spite of the fact that many villagers had

assisted the guerrillas—and repulsed the attacks. This was enormously heartening for both the Home Guards and their advocates.

TEMPLER’S DEPARTURE MARKED the end of the Cromwell-like era of one man having both civil and military powers. Templer’s deputy

high commissioner ascended to take over state finances and high policy. Lieutenant General Sir Geoffrey Bourne took command

of the soldiers and police. Under their leadership, the next three years witnessed tremendous progress on both the political

and military fronts.

By the end of 1955, British intelligence estimated that Communist strength had shrunk from a peak of 8,000 armed guerrillas

to around 3,000. Every metric indicated that the food denial policy was working. The local population was increasingly cooperating

with security forces. Their assistance led to the elimination of virtually all Communist forces in South Selango. Likewise,

in the state of Pahang security forces eliminated an estimated 80 percent of enemy forces, thereby creating the largest White

Area in the country. The trend toward victory continued. In 1956 the security forces lost forty-seven killed. By the next

year this total fell to eleven; the year after, ten. In 1959 and 1960 only one policeman died due to insurgent activity.

While losses among the security forces declined, the army and police continued to whittle away at the remaining insurgents.

During 1957 the rate of guerrilla elimination averaged one per day. During the last years of the Emergency this steady rate

of attrition reduced insurgent numbers to some 500 hard-core guerrillas operating in small groups of five to twenty men. They

lived like hunted animals, incapable of meaningful military operations, intent only on survival. They had entirely lost the

initiative. Only two hopes for insurgent victory remained: popular discontent with the Emergency regulations, particularly

the food denial policies, would spawn some kind of popular rebellion, or the government would make a new, colossal blunder.