June Bug (3 page)

“That was real nice of you,” he said. “Thanks for going to the extra trouble. She appreciated it.”

“What about you?”

“I did too.”

“I heard the manager tell one of our employees that he was calling the tow truck tomorrow if you were still here.”

“You think he’d do that? just kick us out?”

“I think he’d kick his own mother off the property if she stayed too long. It’s always the bottom line with him. Black-and-white, no grays.” She looked up at him, and the flickering fluorescent light hit her face just right—a half silhouette and half halo. I thought this could be a scene from my life I might remember forever—the scene where I finally get a mother.

“I hope you don’t mind me saying this . . . ,” Sheila said.

Dad moved a few paces away, probably so I couldn’t hear, but I got closer to the screen. “Let me guess,” he said. “This is no life for a little girl. She needs a mother. Is that it?”

Sheila smiled. “She needs a school where she can make friends and go to Girl Scouts and learn how to cook.”

You tell him, Sheila.

“She’s learned a lot out here you could never learn in a classroom. I’ve taught her to read and write. She knows the country a lot better than most adults. She can tell you the capital of every state in the Union.”

“She doesn’t have a bicycle,” Sheila said. And then she got quiet like she was sorry she had said it, but I wasn’t.

I felt something warm on my cheek and brushed it away. It was like this lady I didn’t even know knew me better than he did.

He nodded. “I know.”

She turned to walk away and my heart almost broke. Then she stopped and looked back. “I put my street address and phone number on the napkin with my e-mail address. You could have the tow truck bring you there. I have some space by the garage where you could park. Just until the part comes.”

“I’m going to walk over to the parts place in the morning. I’ll bet it’ll be in and we’ll be on the road.”

“Just in case you need it.”

I watched her walk back into a dark spot in the parking lot. Before Daddy came inside, I jumped into bed and pulled the covers over me so he wouldn’t see my eyes. He put a hand on my shoulder and whispered good night. I just lay there and didn’t say anything, pretending I was asleep, this warm and hollow feeling down deep inside at the same time.

All I could think about was the name Natalie Anne. And if somewhere out there was a mother who was waiting for me.

A hard knock at the door woke me from a deep sleep. The sun glinted off the red rocks of the mountain across the interstate. Over there, a truck stop was coming to life with 18-wheelers pulling out in a line. Daddy’s bed was empty at the other end of the RV, the covers all messed up, so I scrambled down and hit the linoleum.

It was the manager of the store, his hand cupped at the window, trying to see inside. I opened the door and noticed something leaning against the front of the RV. A pink bike with a white basket on the front and those streamer things on the handlebars. The thing took my breath away, and all I could do was stare at it and wonder where it came from and who had bought it or if it was some kind of mistake.

“Your daddy in there?” the manager said.

“No, sir.”

The man sighed like I’d just told him the world was coming to an end on Thursday and he was going fishing on Friday. “Know when he’ll be back?”

I shook my head.

“When he gets back, you tell him to come inside the store there and see me.” He pointed to the Walmart like I’d never seen it before or like I was some little idiot kid who couldn’t figure out two plus two. “You hear me?”

“Yes, sir. I’ll tell him.”

“If he doesn’t get back before noon, I’m calling the tow truck. You have any way to get ahold of him?”

The man had just eaten a breakfast burrito or something because I could see white stuff between his front teeth and his breath smelled spicy. I wished I didn’t have to talk with him and that Daddy was back.

“No, sir.”

He swore, then mumbled something about leaving a kid out here alone as he pulled a pack of cigarettes from his pocket and lit one up. He looked down at the bike and scowled. At least that’s the only way I can think of describing it. It wasn’t a sneer; he kind of turned up his nose and said, “This your new bike?”

“I don’t know.”

He sighed again. “You tell him to come see me.” Then he walked off fast, his shoes hitting the pavement hard. He pushed a couple of carts together and moved off toward the grocery entrance. I looked at my watch and it said 6:54.

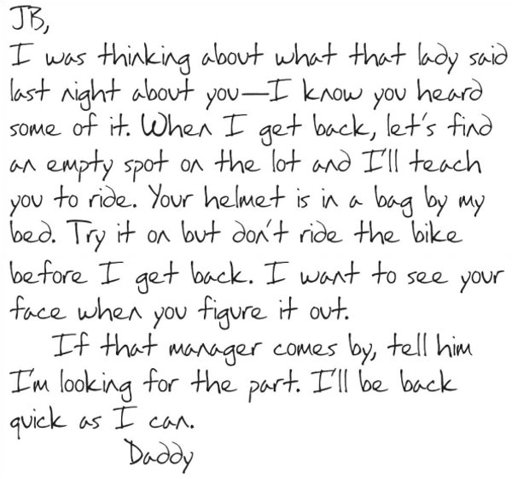

There was a note taped to the bike’s seat, and I climbed down to get it. On the envelope in big letters it said

JB.

Inside was a piece of paper with his scrawl in pencil. When he was teaching me to write, he used the big lined paper and made sure he always printed things nice and neat, but the rest of the time he let his hand go and it was hard to read.

I thought about running after the man and telling him where Daddy was, but I figured I’d better leave well enough alone. I flew into the RV and tried to get the helmet out of the box. It was a chore, but I did it. After I’d pulled all the stickers off, I put it on and ran for my mirror. The helmet was the most shiny and beautiful thing I’d ever seen, but I couldn’t figure out how to get the strap fastened because it was too tight. On the counter was a little white bag with a donut inside. I ate it while I went outside and walked around the bike. It had white tires and white handlebars and white pedals, and the rest of it was pink.

If this was the effect of having a mother, I was all for it.

Sheila arrived a half hour early for work, her heart fluttering as she exited the interstate and wound her way around the other grocery and drugstores. She usually drove to the light and turned, but she didn’t want to get caught by it, so she pulled into The Home Depot and drove to the end where she’d have a good view of the parking lot.

The RV was still there.

She took the fresh loaf of banana-nut bread and knocked on the door. No answer. She opened it and put the loaf on the counter. In the light of day and with the shades open, she could see a bit more of their lives. Everything the girl owned was on her bed. A pile of notebooks mostly. Where did she keep her clothes?

The RV could have been worse, though Sheila wasn’t sure how. Maybe if there were raw meat on the floor and rats gnawing at it. The night before, the small living space had looked quaint in a way. Now it was just sad. It had to be difficult to live in a confined space without it becoming a trash heap, but these two clearly needed tips on clutter management. It looked like the girl slept in a sleeping bag on top of the mattress. A permanent campout.

A box of granola sat on the counter. An opened can of Pringles beside it. A half-eaten box of Oreos. A stack of old newspapers. Several blue plastic bags from the store. The couch, if you could call it that, was ripped and had crumbs strewn around, along with a torn cardboard box. His bed was unmade with only a throw draped over the mattress, no sheets. The computer sat on the floor by his bed. A half-empty cup of coffee from a nearby shop perched precariously on a shelf. Maybe the coffee shop was how he charged the computer and used the Internet.

Suddenly, something about his work didn’t feel right. As soon as she’d gotten home the night before, she checked her e-mail to see if he had sent her a message, but there was nothing. Just a message from her sister about the negative effects of aspartame and how she needed to quit drinking diet soda. That and a few spam e-mails.

It was a glance at their lives, just a fleeting look at the way they lived, but she found herself judging them—him, really. Questions flooded. Where was the girl’s mother? Was he on the run? If so, from who? Or what?

She’d had this feeling before, a stirring in the gut that something was amiss, something didn’t fit. A sensation at the soul level, somewhere between marrow and bone and emotion that told her to be wary. At those times, she had dismissed the feeling as simple reserve, an unwillingness to commit to life, to move forward. And some of those moves had been disastrous.

This does not feel right.

Only one thing surprised her in the whole RV. By the head of the bed, on top of the built-in cabinets, next to several rolls of stacked toilet paper, was a weathered Bible. It sat open, as if it had been recently read. Her parents had kept a family Bible on a coffee table in the living room when she was a child. It was more of a good luck charm than anything, for the family certainly didn’t read it, and they only hit church on the high holidays.

The sight made her want to run. She felt as if she were treading on some sacred burial ground and that brought a chill.

What if this guy is a serial killer and the girl was the daughter of one of his victims? The two don’t look that much alike—no resemblance other than the eyes. Or he could be one of those perverts who kidnaps kids and moves from town to town until he gets tired of them and finds another.

She quickly retrieved the bread, stuffed it in her purse, and hurried out the door. Sweat trickled down her back, and she wiped at her forehead as she scurried across the parking lot in the hot morning sun.

The entrance hit her with a blast of cool air and a greeter said, “Good morning, Sheila.” Delores was wiry and older, with a nice smile and hair that could be described only as patchy.

Sheila didn’t want to face the crew and the questions that would undoubtedly be waiting, so she turned right, needing a refill of her blood pressure medication, a problem handed down from her mother. There was no one at the front counter, so she walked past the aisles of painkillers, diabetic supplies, and supplements until she found the pharmacist and two other workers staring at the black-and-white monitor for drive-up prescriptions.

“Isn’t that cute?” a young assistant said. She had flowing black hair and a pretty face, and Sheila couldn’t help but wonder if the dark-haired boy with the black trench coat and earring in his eyebrow who hung around at closing wouldn’t be her undoing someday. An assistant manager has to know as much as she can about her employees and struggle with the information.

“She got it,” the pharmacist said, laughing. “Look at her go! I wish I could record this.”

Sheila moved to the end of the counter so she could see the monitor. In the empty lot behind the store stood a tall figure watching a smaller figure pedal a bicycle.

“Isn’t that something,” the assistant said, biting her lip. “I remember when my dad taught me to ride.”

“It’s like watching someone take Communion for the first time.”

Sheila turned and walked away.

Johnson stood transfixed, watching the perfection of momentum, speed, and balance. Pink and white and a little girl smiling was the best thing he had seen all day. Maybe all year. He hadn’t thought about a bike for June Bug, but now it seemed like the perfect fill to the void growing ever wider. The void of the present and the future.

He had loosened the straps for the helmet and positioned it on her head correctly, just as the box said. The back of the store seemed a good bet, less traffic and no slope. The only problem was that the aroma of fire-grilled food coming from the nearby Texas Roadhouse had his stomach growling.

It hadn’t taken her five minutes to put it all together and begin to ride with abandon. Braking was still a foreign concept, but he guessed that was the way of children. Old people are more concerned with stopping than going. Kids just want to go, and he wasn’t about to rain on her pedal parade. In time she’d get all the stopping she wanted and then some.

In a white T-shirt and jeans, he watched, his own childhood flooding back in a patchwork of memories like some quilt strung together from vulnerable moments. Riding by himself down the short gravel drive leading away from their house. Lost momentum, falling, skin on rocks. Blood. Laughter behind him. Some people viewed parents as those who stand on one side of a room and encourage you to walk, cajoling you to get up and try again. Johnson had experienced the opposite. It had taken years to shake the feeling of ridicule and scorn he expected just for getting up and putting one foot in front of the other. Since birth, his view of the world had always been of people—and even God—waiting for his fall and then piling on. Success was simply staying down and surviving.