Julia's Kitchen Wisdom (30 page)

Read Julia's Kitchen Wisdom Online

Authors: Julia Child

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #American, #General, #French, #Reference

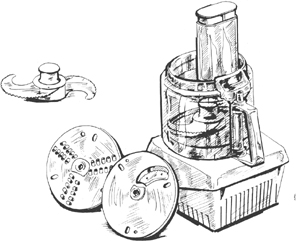

The Food Processor

This marvelous machine came into our kitchens in the mid-seventies. The processor has revolutionized cooking, making child’s play of some of the most complicated dishes of the

haute cuisine

—mousses in minutes. Besides all kinds of rapid slicing, chopping, puréeing, and the like, it makes a fine pie crust dough, mayonnaise, and many of the yeast doughs. No serious cook should be without a food processor, especially since respectable budget models can be bought very reasonably.

Mortar and Pestle

Small mortars of wood or porcelain are useful for grinding herbs, pounding nuts, and the like. The large mortars are of marble, and are used for pounding or puréeing shellfish, forcemeats, and so on. The electric blender, meat grinder, and food mill take the place of a mortar and pestle in many instances.

Heavy-Duty Electric Mixer

Whip, for eggs

Dough Hook

Flat Beater, for heavy batters, ground meat, etc.

A heavy-duty electric mixer makes light work of heavy meat mixtures, fruit cake batters, and yeast doughs as well as beating egg whites beautifully and effortlessly. Its efficient whip not only revolves about itself, but circulates around the properly designed bowl, keeping all of the mass of egg whites in motion all of the time. Other useful attachments include a meat grinder with sausage-stuffing horn and a hot-water jack which attaches to the bottom of the stainless steel bowl. It’s expensive, but solidly built and a life-long aid to anyone who does lots of cooking.

DEFINITIONS

BASTE

,

arroser:

To spoon melted butter, fat, or liquid over foods.

BEAT

,

fouetter:

To mix foods or liquids thoroughly and vigorously with a spoon, fork, or whip, or an electric beater. When you beat, train yourself to use your lower-arm and wrist muscles; if you beat from your shoulder you will tire quickly.

BLANCH

,

blanchir:

To plunge food into boiling water and to boil it until it has softened, or wilted, or is partially or fully cooked. Food is also blanched to remove too strong a taste, such as for cabbage or onions, or the salty, smoky taste of bacon.

BLEND

,

mélanger:

To mix foods together in a less vigorous way than by beating, usually with a fork, spoon, or spatula.

BOIL

,

boullir:

Liquid is technically at the boil when it is seething, rolling, and sending up bubbles. But in practice there are slow, medium, and fast boils. A very slow boil, when the liquid is hardly moving

except for a bubble at one point, is called to simmer,

mijoter.

An even slower boil with no bubble, only the barest movement on the surface of the liquid, is called “to shiver,”

frémir

, and is used for poaching fish or other delicate foods.

BRAISE

,

brasier:

To brown foods in fat, then cook them in a covered casserole with a small amount of liquid. We have also used the term for vegetables cooked in butter in a covered casserole, as there is no English equivalent for

étuver.

COAT A SPOON

,

napper la cuillère:

This term is used to indicate the thickness of a sauce, and it seems the only way to describe it. A spoon dipped into a cream soup and withdrawn would be coated with a thin film of soup. Dipped into a sauce destined to cover food, the spoon would emerge with a fairly thick coating.

DEGLAZE

,

déglacer:

After meat has been roasted or sautéed, and the pan degreased, liquid is poured into the pan and all the flavorful coagulated cooking juices are scraped into it as it simmers. This is an important step in the preparation of all meat sauces from the simplest to the most elaborate, for the deglaze becomes part of the sauce, incorporating into it some of the flavor of the meat. Thus sauce and meat are a logical complement to each other.

DEGREASE

,

dégrassier:

To remove accumulated fat from the surface of hot liquids.

Sauces, Soups, and Stocks

To remove accumulated fat from the surface of a sauce, soup, or stock which is simmering, use a long-handled spoon and draw it over the surface, dipping up a thin layer of fat. It is not necessary to remove all the fat at this time.

When the cooking is done, remove all the fat. If the liquid is still hot, let it settle for 5 minutes so the fat will rise to the surface. Then spoon it off, tipping the pot or kettle so that a heavier fat deposit will collect at one side and can more easily be removed. When you have taken up as much as you can—it is never a quick process—draw strips of paper towels over the surface until the last floating fat globules have been blotted up.

It is easier, of course, to chill the liquid, for then the fat congeals on the surface and can be scraped off.

Roasts

To remove fat from a pan while the meat is still roasting, tilt the pan and scoop out the fat which collects in the corner. Use a bulb baster or a big spoon. It is never necessary to remove all the fat at this time, just the excess. This degreasing should be done quickly, so your oven will not cool. If you take a long time over it, add a few extra minutes to your total roasting figure.

After the roast has been taken from the pan, tilt the pan, then with a spoon or a bulb baster remove the fat that collects in one corner, but do not take up the browned juices, as these will go into your sauce. Usually a tablespoon or two of fat

is left in the pan; it will give body and flavor to the sauce.

Another method—and this can be useful if you have lots of juice—is to place a trayful of ice cubes in a sieve lined with 2 or 3 thicknesses of damp cheesecloth and set over a saucepan. Pour the fat and juices over the ice cubes; most of the fat will collect and congeal on the ice. As some of the ice will melt into the saucepan, rapidly boil down the juices to concentrate their flavor.

Casseroles

For stews,

daubes

, and other foods which cook in a casserole, tip the casserole and the fat will collect at one side. Spoon it off, or suck it up with a bulb baster. Or strain off all the sauce into a pan, by placing the casserole cover askew and holding the casserole in both hands with your thumbs clamped to the cover while you pour out the liquid. Then degrease the sauce in the pan, and return the sauce to the casserole. Or use a degreasing pitcher into which you pour the hot meat juices, let the fat rise to the surface, then pour out clear juices—the spout opening is at the bottom of the pitcher; stop when fat appears in the spout.

DICE

,

couper en dés:

To cut food into cubes the shape of dice, usually about ⅛ inch.

FOLD

,

incorporer:

To blend a fragile mixture, such as beaten egg whites, delicately into a heavier mixture, such as a soufflé base. This is described in the

cake section

. To fold also means to mix delicately without breaking or mashing, such as folding cooked artichoke hearts or brains into a sauce.

GRATINÉ:

To brown the top of a sauced dish, usually under a hot broiler. A sprinkling of bread crumbs or grated cheese, and dots of butter, help to form a light brown covering (

gratin

) over the sauce.

MACERATE

,

macérer;

MARINATE

,

mariner:

To place foods in a liquid so they will absorb flavor, or become more tender. Macerate is the term usually reserved for fruits, such as: cherries macerated in sugar and alcohol. Marinate is used for meats: beef marinated in red wine. A marinade is a pickle, brine, or souse, or a mixture of wine or vinegar, oil, and condiments.

MINCE

,

hacher:

To chop foods very fine.

NAP

,

napper:

To cover food with a sauce which is thick enough to adhere, but supple enough so that the outlines of the food are preserved.

POACH

,

pocher:

Food submerged and cooked in a liquid that is barely simmering or shivering.

PURÉE

,

réduire en purée:

To render solid foods into a mash, such as applesauce or mashed potatoes. This may be done in a mortar, a meat grinder, a food mill, an electric blender, or through a sieve.

REDUCE

,

réduire:

To boil down a liquid, reducing it in quantity, and concentrating its taste. This is a most important step in saucemaking.

REFRESH

,

rafraîchir:

To plunge hot food into cold water in order to cool it quickly and stop the cooking process, or to wash it off.

SAUTÉ

,

sauter:

To cook and brown food in a very small quantity of very hot fat, usually in an open skillet. You may sauté food merely to brown it, as you brown the beef for a stew. Or you may sauté until the food is cooked through, as for slices of liver. Sautéing is one of the most important of the primary cooking techniques, and it is often badly done because one of the following points has not been observed:

1. The sautéing fat must be very hot, almost smoking, before the food goes into the pan, otherwise there will be no sealing-in of juices, and no browning. The sautéing medium may be fat, oil, or butter and oil. Plain butter cannot be heated to the required temperature without burning, so it must either be fortified with oil or be clarified—rid of it’s milky residue as described

here

.

2. The food must be absolutely dry. It if is damp, a layer of steam develops between the food and the fat preventing the browning and searing process.

3. The pan must not be crowded. Enough air space must be left between each piece of food or it will steam rather than brown, and its juices will escape and burn.

TOSS

,

faire sauter:

Instead of turning food with a spoon or a spatula, you can make it flip over by tossing the pan. The classic example is tossing a pancake so it flips over in mid-air. But tossing is also a useful technique for cooking vegetables, as a toss is often less bruising than a turn. If you are cooking in a covered casserole, grasp it in both hands with your thumbs clamped to the cover. Toss the pan with an up-and-down, slightly jerky, circular motion. The contents will flip over and change cooking levels. For an open saucepan use the same movement, holding the handle with both hands, thumbs up. A back-and-forth slide is used for a skillet. Give it a very slight upward jerk just as you draw it back toward you.

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Child was born in Pasadena, California. She graduated from Smith College and worked for the OSS during World War II in Ceylon and China. Afterward she and her husband, Paul, lived in Paris, where she studied at the Cordon Bleu, and taught cooking with Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, with whom she wrote the first volume of

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

(1961).