Joyland (7 page)

J.P. dodged ahead. He didn’t mean just any car. He meant

the car

. Mr. Breton’s crash derby special. “Had to get Marc to help get it down here. Son of a bitch.” Even as J.P. swore, his voice rose like a high school girl’s. Chris watched him wipe sweaty palms on the ass of his shorts. The day Mr. Breton had brought the old Dodge wagon home, he’d demonstrated, using ether to bring it back to life. It made a violent

clack clack clack!

, like a baton dragged across jail bars. J.P. and Chris had painted it black and white, like a police cruiser.

OPP

, J.P. had hand lettered the sides, and instead of

Ontario Provincial Police

, he’d painted

Optimal Playing Power

in tiny script underneath.

They took off, swerving through the post-parade crowd. All the while, Chris kept eyes peeled for girls his age, girls who might be in his classes come September. Jostling between tank-topped bodies, there was the instant mental sorting: too old, too young. A fresh-looking blonde covered her mouth as she laughed. Sweet, but seventh-gradish. Chris squeezed past a gang of confident smokers — chubby legs announcing themselves to the world in cut-offs. Fifteen. The one in the sparkly lettered T-shirt glared as Chris’s shoulder grazed her chest.

J.P. followed, smirking. He made a sucking noise when they were safely through.

“You wasted that one.”

Chris didn’t look back. He could feel a pack of angry eyes on him. Unconsciously he touched his fingers to his shoulder, as if it were holy now, as if it had touched the robe of Jesus. In truth, her breast had felt like anything else under cotton: elbow, shoulder, stomach.

“I didn’t mean it,” he said, fingers jerking away from the spot. He walked away fast through the crowd.

“Pffft. That’s your problem,” J.P. laughed.

Scanning the people in the street, Chris hoped for a glimpse of Laurel Richards, the one and only girl who had ever played worth a damn at Joyland. Her thin limbs were called to the forefront of his brain by the smell of suntan oil rising around them, Piña-Colada-prevalent. Laurel hadn’t been there yesterday, and that seemed to Chris more tragic than anything he could imagine.

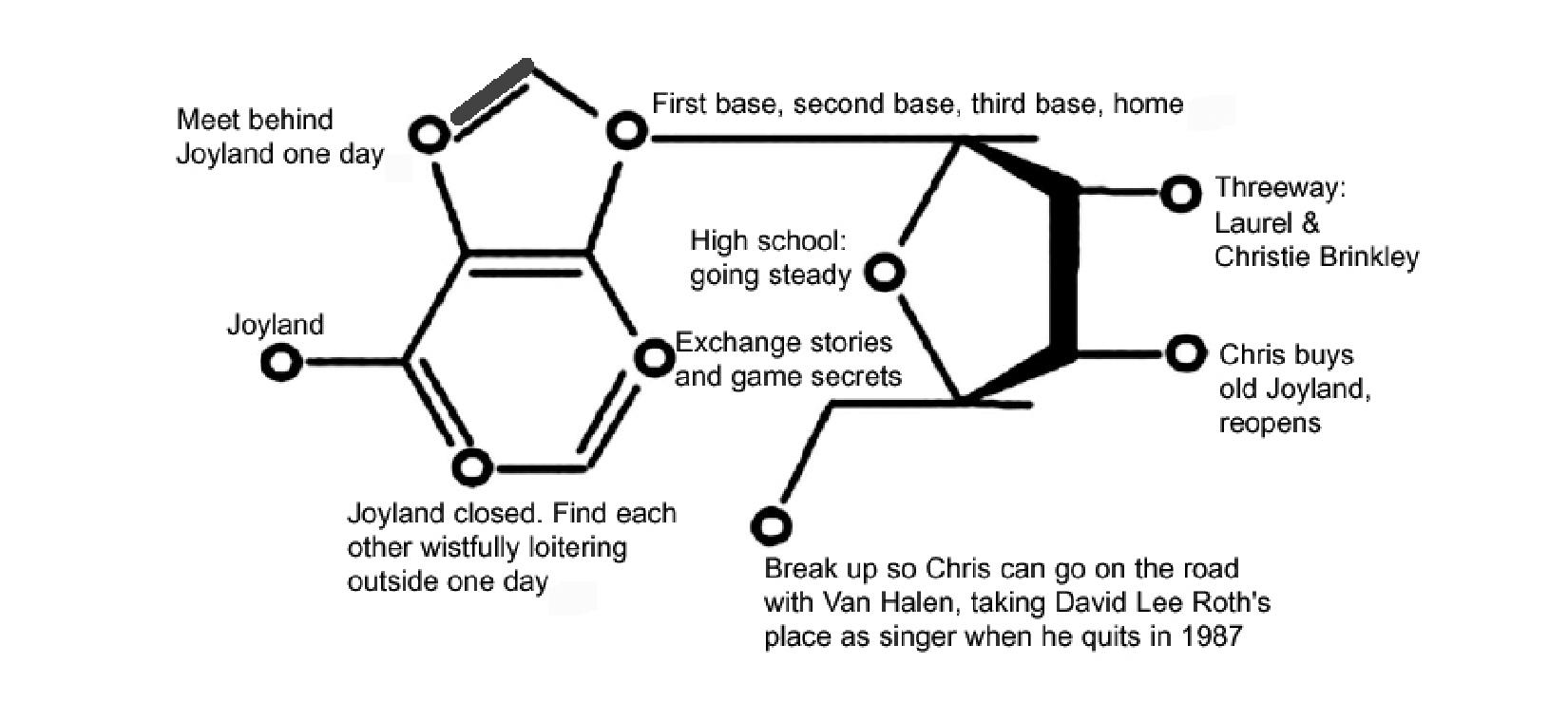

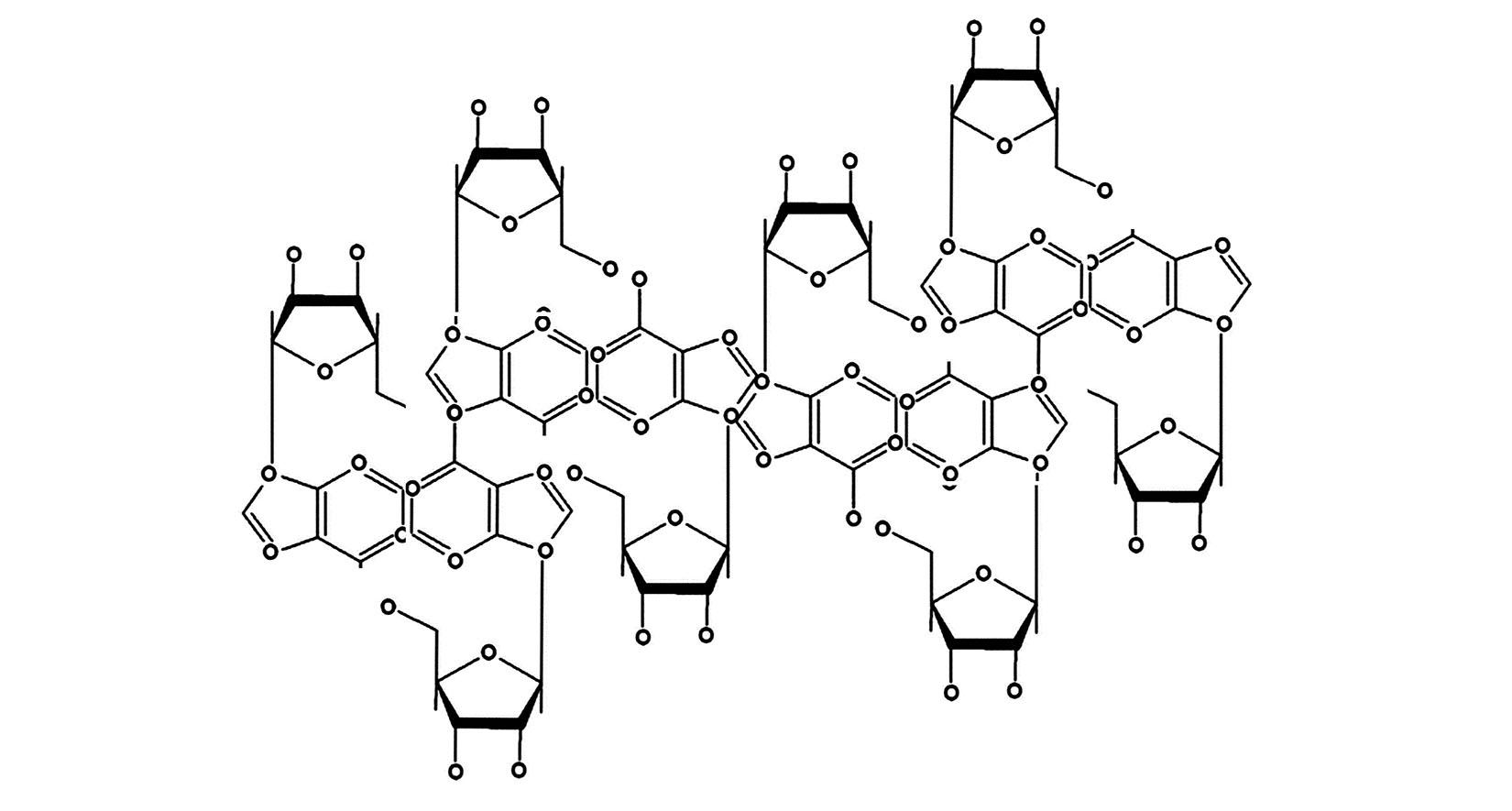

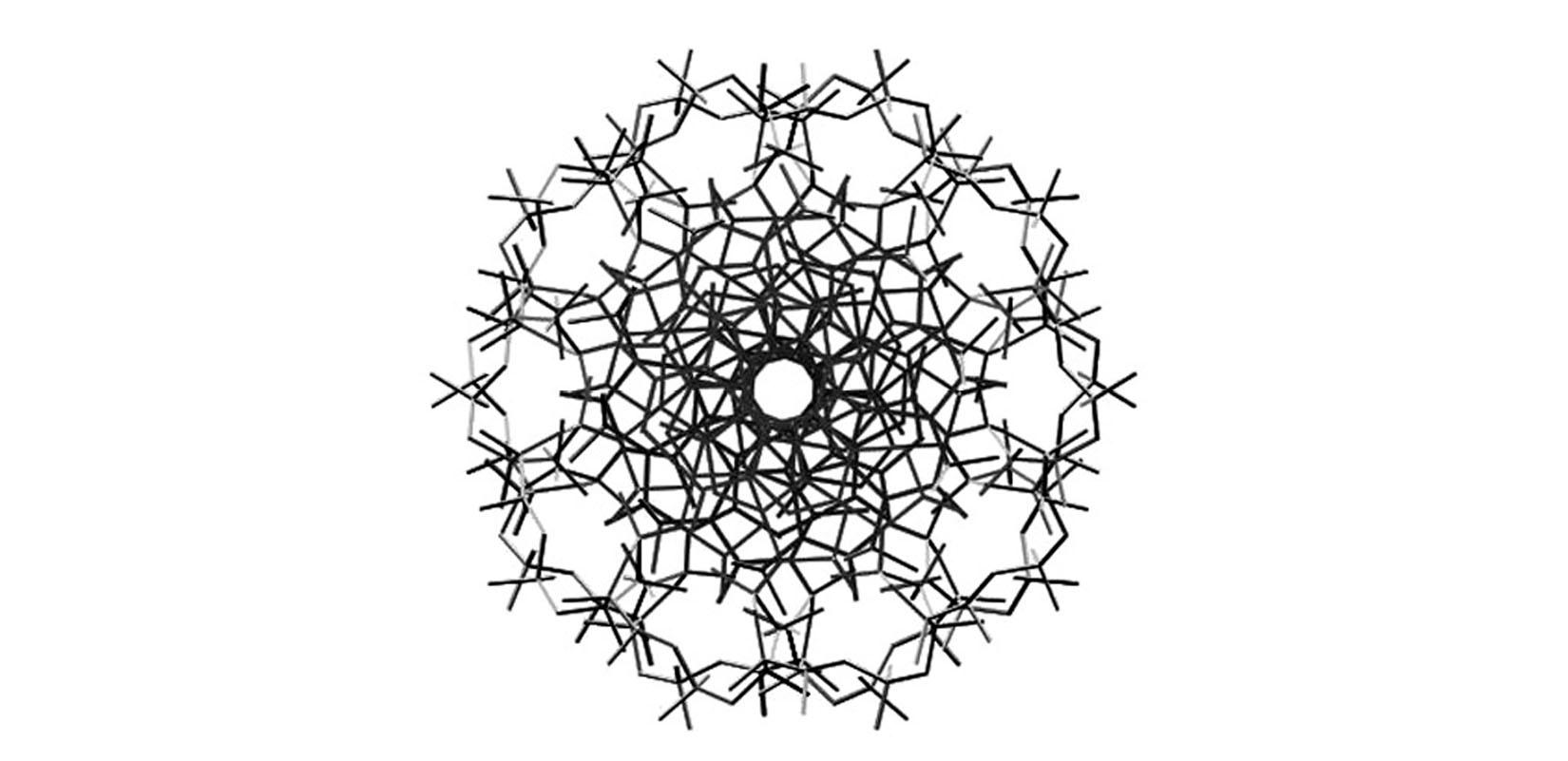

From the moment Chris first saw Laurel in Joyland, he began to construct a timeline in his mind of the direction their lives would take. It began with her peering into the game, followed by his exponential masturbation. From that point on, however, there was one major problem with the timeline: Chris’s tendency to revise it. Always, it started at the same moment, but the hinges in the line and the words relating to them became erased so many times, as Chris’s daydreams expanded and exploded, that eventually Chris stopped his mental erasing. Their timeline became a 3D figure, similar in shape to a molecular compound. It began as a simple nucleotide, maybe an adenosine, with several bulbs and branches, then double-helixed and spread until it was as complex, as astral, as DNA.

FIG. 1: Timeline of Chris Lane and Laurel Richards’ Relationship

FIG. 2: Timeline of Chris Lane and Laurel Richards’ Relationship

FIG. 3: Timeline of Chris Lane and Laurel Richards’ Relationship, Three-Dimensional View

LEVEL 4:

CENTIPEDE

PLAYER 2

The purse pitched back and forth like a pendulum, harder and harder, until the contents grew heavy and nearly forced Tammy forward.

“Mom!” she hollered, stopping the motion abruptly with her left hand. The strap wrapped around it, quickly cutting off circulation. She untangled herself, pulled the zipper back, dug around for her mother’s car keys. From the bathroom, running water. Tammy twirled the keys around the ring on her thumb: leather tab key chain, engraved “No. 1 Mom.” Tammy stared at it in her hand. The key ring was the diameter of the mouth of a pop bottle, she realized. The mouth of a pop bottle . . . About the same size, her best friend Samantha Sturges had said, of Samantha’s thirteen-year-old cousin’s wiener, which she had seen last summer while changing in the back seat of the car to go swimming.

“He’ll be there again this year,” Samantha had said last week, about going to the beach for fireworks night.

“But he’s your cousin,” Tammy had pointed out.

“So? He’s still

gorgeous

.” In Samantha’s book, being

gorgeous

was all anything was ever about. She wondered if Sam had seen it by accident or on purpose. Tammy hadn’t thought to ask. She had seen Chris’s before, but that was years ago — she hardly remembered — before she even knew about s-e-x. When she’d asked Sam tentatively what it looked like, Sam had confided,

“Weird.

Like the neck of a pop bottle covered in Silly Putty.”

Mrs. Lane came into the living room, where Tammy was standing staring down at “No. 1 Mom.” Mrs. Lane put out her hand and the silver ring with the leather tab fell from Tammy’s palm to hers.

“Don’t dig through my purse,” she said, taking the strap and looping it over her shoulder as they walked out, one behind the other.

On the ride over to the Sturges’s, Mrs. Lane rolled a cigarette between filament-thin fingers, and placed the end tentatively in her mouth. She seemed to nibble at it, as if considering whether to spark it up or not. Tammy watched the end bounce up and down as her mother contemplated. She took the cigarette out and, rolling it once more between her fingers, as if she could consume it through her skin, placed it in the ashtray. The end was wet now, like a lipstickless kiss. The paper clung to the things rolled up tight inside it, showing through, vaguely, brownly.

Gross.

Tammy turned to the passenger window. She pushed the shoulder strap of the seatbelt down beneath her arm and leaned back against it, leaving only the lap belt in effect.

They inched out onto St. Lawrence Street, traffic all stops and starts, the town rerouted around the stretch of Canada Day game booths. A gigantic, purple balloon head bobbed behind the Kentucky Fried Chicken. Tammy watched it — the inflatable jumping booth — wondering if it was dumb to want a ticket.

Under Twelve,

the sign said. Tammy knew this, though she couldn’t see it from where they idled. She remembered from last year that she’d had one more year left.

Mrs. Lane put her blinker on, started to edge over.

“Damn,” she said softly. She paused, signalled again, and eased over, waiting.

Samantha lived in what Tammy secretly called the “left ovary” of South Wakefield. Everyone else called it Forest Hill: a new maple-bricked subdivision with double driveways and pencil-thin trees. Sam had arrived four years ago, joining Tammy’s class at school with a package of Magic Markers, as if she’d sprung, miraculously, half-grown from the dirt mounds that would gradually transform into her neighbours’ foundations. St. Lawrence Street branched into a triangular subdivision and two more main streets (King and Jamison) heading in opposite directions, ends extending into cul-de-sacs. The left (northern) ovary was Forest Hill. The right was not fortunate enough to have a name, called only Southside or south South Wakefield. In pink-on-pink-on-white glossy, Tammy had traced the contours: a sex-ed. booklet given by Samantha’s mother to Sam. Chancing upon an aerial photograph of the town in the library a week later, the analogy came clear. Located toward the bottom of Ontario — at the very bottom of all of Canada in fact — South Wakefield was the sex organ no one ever talked about.

The idea implanted itself in Samantha and grew to proportions beyond Tammy’s timid brain.

“Va — gina,”

she would mouth to Tammy, across the room at school, for no reason but to see Tammy turn bright red and bend over her desk, hair hitting the blue lines of her notebook. “You live in the

va — gina.”

Dirty words were a wonderful thing to Sam. She saved up a list of them for every situation. A year dangled between the two girls like a spider on a thread. Sam had been held back in kindergarten due to poor attendance. A sinister case of pneumonia, or so she said. But Samantha said a lot of things. She was a reference queen, from Terrabithia trees to dictionaried profanity. She said that she could go out with any guy she wanted,

just like that,

as she snapped her fingers.

Tammy let her arm fall casually out the car window. The air resisted her cupped hand with a muted

whoosh-whoosh

. Keeping the hand low, against the door, so her mother wouldn’t see, Tammy closed her eyes and felt the motion of the car, tried to gauge whether they had passed the pharmacy or the post office yet. Tammy knew when the car was crossing the bridge, between the incline and the

thruuuuum

as the tires found traction. She felt the sting of a bug in her hand, and opened her eyes, yanking her arm back through the window. Mrs. Lane glanced from the cigarette in the ashtray to Tammy. Then her eyes flicked quickly back to the road. She turned somewhat too sharply onto Sam’s crescent.

The Sturges’s house had a For Sale sign pounded into the front lawn, exactly centred between the two trees that still hadn’t grown large enough for climbing.

“He’s not going to be there, is he?” Mrs. Lane asked. By “he,” she meant Mr. Sturges. Tammy shook her head.

“So it’s all finally going through?”

The sun fell into Tammy’s lap through the windshield, sealing her thighs to the vinyl seat with sweat. She didn’t look up.