Joyland (28 page)

— the thing was —

Tick.

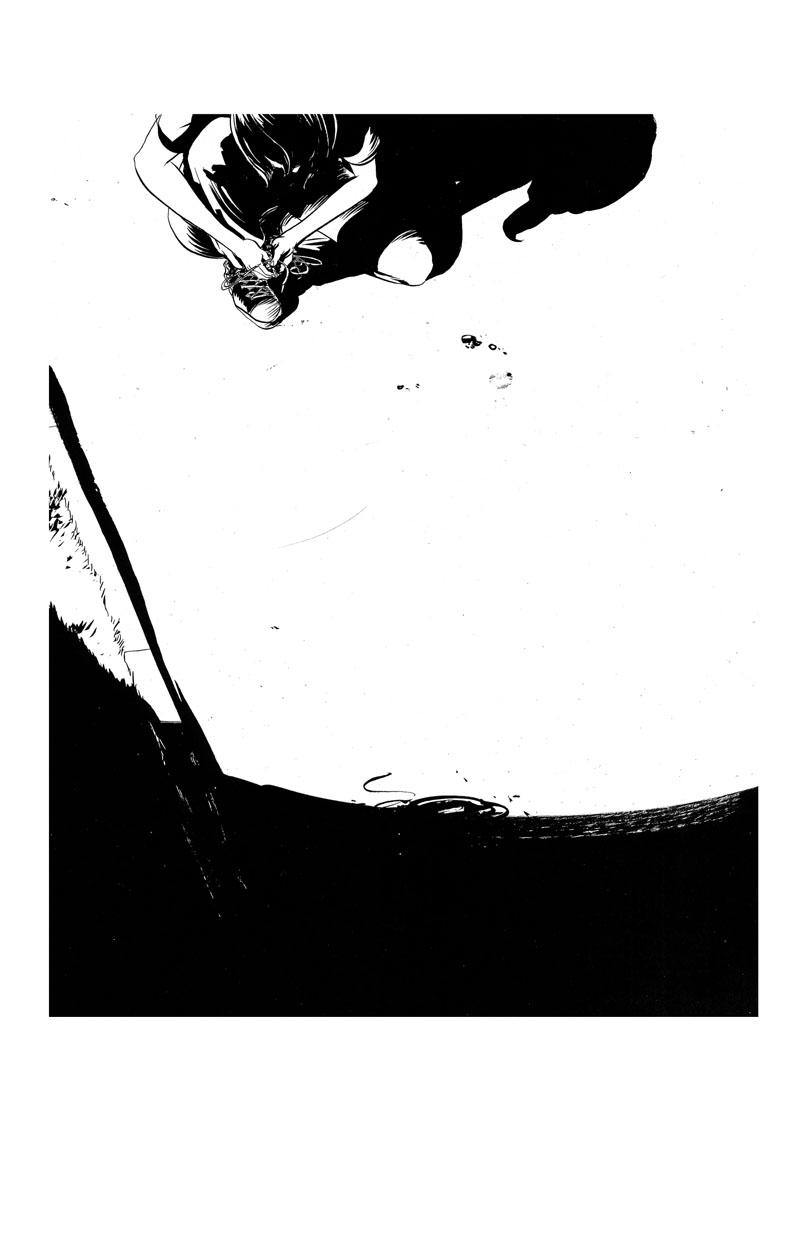

Marc’s front wheel shot past the snout of the van. The bike tire whistled over the concrete. Chris opened his mouth to

yell — to make some sort of unplanned gesture, sign — stop it. Marc’s hand wrapped around the thing in his back pocket, which Chris saw very clearly now. It was not a comb because — in spite of the Bretons’ foyer photograph — Marc had a quarter-inch buzz cut.

There was a swerving of bodies and bikes as Adam descended. On the other side of the circle — what seemed a long way away — David and Kenny rolled out to watch. Silence battered Chris’s ears. He braked.

Adam reached out, got a hand on Marc. Swiping a meat hook around his neck, Adam pulled to topple him from the ten-speed, managed a good jab. His fist cracked against Marc’s face in a splinter of knuckle and skin. The bikes seemed to float. Marc reached backward again — even as he began to waver, even as his head snapped. His fingers ratcheded the thing from his back pocket.

It was a handle. Even before it came completely into sight, Chris knew that it was longer than a girl’s hand and as heavy as cast iron. Marc’s back pocket slowly unsheathed the thing — the intricate sabre replica, suddenly a basic piece of lead pipe.

It was all Chris could do — to stand there and see, to know the thing before it happened. He opened his mouth. He opened his mouth. He opened his mouth. There was no sound.

Chris realized he hadn’t moved, wasn’t moving, was in fact the only one who had stopped dead. One leg raised on the pedal, the other flat on the ground, Chris watched his premonition bloom into reality, the colour of blood on concrete.

Marc’s bike clattered to the ground and he pitched with it straight into Adam, his hand thrusting forward suddenly. The glinting nub of metal smashed into Adam’s open mouth. A loud crack shook the air — the shock of teeth and bone exhumed from skin and gum. Before the red bleared downward, Marc had brought his fist back for a second blow.

This was where Chris yelled

Stop!

This was where Chris became the hero. This was where the world slammed a gigantic brake and Chris avenged all the wrongs of the universe in less than a second.

This was where Chris stood still — breath flapping in his chest like it would tear clean through him — and watched, watched the sky tip over, watched the other boys sink into recognition as they also slowly stopped, each putting a foot down tentatively against the ground. A thick fire reached a thick hand through Chris’s throat, as he watched helplessly, his messenger quickly disabled.

The hilt of the

Star Wars

sabre landed with a dull thud against Adam’s temple. Adam toppled into a swatch of red. His forehead palpitated with fleshy matter, burst like an overstuffed cushion. There was a warm, soft gush — a rush of things Chris would later claim he had not seen.

The world between Chris and Marc wavered as Chris caught Marc’s arm. Marc jerked back hard, the metal flying out of his grip. It rang across the concrete as his knuckles grazed haphazardly off Chris’s collarbone. Chris reeled backward. Marc’s face was like a hammer, one small, bright freckle of blood clinging to his cheek. He glared at Chris without seeing him, jerked away. Marc picked up his bike, swerved the front tire around one of Adam’s bent legs. Shakily he swung himself over the crossbar, and rode away without taking his hands off the handlebars.

LEVEL 13:

BERZERK

PLAYER 1

In the timelines of Chris’s sci-fi novels, cause and effect remained lateral. Everything would move in a horizontal manner, back and forth across the page. History would hold a spear, and everything would embed itself upon that straight-line steel like a shish kebab. Love, deceit, mechanical error — these meaty treatises were penetrated by time, one act added after another. But in Chris’s video games, there was room for upward movement. On each and every board, his icon ran to and fro, moved in and out of rooms or states of peril, and eventually proceeded upward into a new playing field. So enter the interlude music, the board between boards . . .

He had felt

it,

sensed time shifting. Now he waited to see where it would deliver them.

Chris had never known that being stuck in a room could be so excruciating. He had always been sent to his bedroom as punishment. In his room he had all his stuff. This was something else entirely. The boys sat on a bench, partitioned off from the main room by brick and thick glass. None of them spoke. In the end, the silence was broken by Marc, far away, down the hall.

They could see him as he was brought in. J.P. stood up and went to the window that looked out on the hall. The rest of them remained seated.

David jabbed Kenny in the ribs. Kenny didn’t respond, except to purse pert lips. His chin, as if in compensation, melted like wax into his throat. He gaped at Chris, as if unaware he was being prodded. From his left side, Dean glared at David, pushed over on the bench away from him, into the space J.P. had just vacated. Dean’s thumbs crisscrossed in his lap, the members of his folded hands that would hit the space bar of the old electric typewriter he would lug to university, while everyone around him dormed their PCs and Smith-Corona 8-line screens upon graffitied desks templed with beer cans. Dean would avoid their student pub with its “Downstairs Thursdays” dance parties and its “Wednesdays Hump-days” $2.50 pints; their bookstore selling crest-emblazoned-clothing; their corporate-sponsored student centre; their cafeteria’s endless mill of sandwiches smeared with mayonnaise, turdish french fries and gravy. Eventually he’d leave their puffy-lettered intellectualizing behind — six credits short of graduation. He would return to the area, marry a girl from the reserve, be asked to take a post in the South Wakefield high school he had not yet stepped into, cultivate a Native Studies program whose courses he would never be technically qualified to teach. He would be hired on as an advisor, talk one teenager out of suicide, steer three away from early careers in alcoholism, and countless others away from incidents like the one he had just witnessed. But his greatest pleasure would come when his fifth daughter won her first South Wakefield fishing contest. Dean shifted further to the left, his thumbs tightened around the air between his hands, closed over what little Chris could see of life between his palms.

On the other side of Chris, Reuben, broad and brown, stared straight ahead, bouncing his knees so that the whole bench jiggled. In its shudder, Chris could feel the desert shifting, the mushroom sun of Nevada. Reuben would drop out of school as soon as it was legal, drive across North America in all directions, smoke everything that crossed his path, and enjoy everyone who offered themselves to him. He would arrive in California at sunrise one pink morning, live there for a short time, then in Vancouver. He would act as an extra, and eventually shine as a commercial actor for a popular laxative. Later, he would return to South Wakefield to take care of his mother. He would apprentice as a plumber, make a decent living. He would be infinitely grateful his commercial never aired in the area, cancelling the possibility of a crude and unmerciful connection between these two career paths, which surely would have resulted in a flood of poor jokes.

Kenny had been the only one to keep his cool after the blow. The rest of them had stood staring down at Adam. Wretched David, ever-cool, even tried to help him up, saying, “He’s fine. It’s nothing.” In two years’ time, perhaps in some stalled reaction, a new man would emerge. Chris had felt it in the brevity of David’s words. Quite suddenly, he would set belligerence upon a shelf one day, crush the shrimpish child in him, begin sleeping flat on his back and waking to a hundred sit-ups, a self-imposed regimen. He would graduate as a police officer, shoot one possibly innocent/possibly deranged-and-dangerous man (charges dropped) and save two children from drowning. Several years later, there would be a third child (a toddler) whom he would pull from an oil pit (dead) and no one — especially not Chris — would ever guess the weight of its half-tarred blue head in his hand, the recurrent image of its toenails dangling, the love in it wasted.

Meanwhile, Kenny had run straight into the Bretons’ house for the phone, hadn’t thought twice about throwing open their front door and dashing through their hall. Now, the shock reversed its effects: David scoffed behind J.P.’s back; Kenny zoned out. And Chris . . . all Chris could think was,

how had he known?

Chris shuddered. It didn’t seem to matter that he hadn’t particularly liked Adam, or that he had only known him for the span of one summer. The suddenness of their lives seared like the welt at Chris’s shoulder, which he rubbed, tentatively, beneath his collar. Where Marc had struck him, a small thistle of pain beneath the bone.

There were things he still didn’t know, things about Adam Granger he would never know, but for the moment, these facts were as minor as the vibrations of the bench trembling beneath Chris. The wall behind his head staticly clutched at hairs.

Escorted by two officers, Marc walked past them. He yielded like a wax figure, face ruddy. A white fist-shaped mark had begun to puff where he’d been struck — four distict spots, the knuckles imprinted in a clean manifestation of their now-deceased owner. It took Chris a minute to process the sound that came out of Marc. He was choking on it, an octave too high, as if he had sucked helium from a valve. The dreadful squalling seized the station. It was stopped short by teeth that refused to open, refused to let the poor noise go.

J.P. put a hand up to the glass, as if to knock on it when Marc went by, but as he came closer, J.P. stiffened. He stopped short, his hand a half-inch away from the partition. His brother passed.

Chris put his head down and lay an arm across his stomach. Beneath him the bench thrummed. A spike of bile jolted in his throat. He willed it back down. Already he knew — in his brain, he knew — that they would be sent home soon enough. A few questions, a stern talking-to. J.P. would be fine. Even Marc would be fine. It was a clear-cut case of self-defence.

But that didn’t matter.

Unwilled, it came to mind, set to repeat. A terrible theme composed of heat. Hand scrabbling backward. Handle unsheathed. Muscles plunging into red. Clattering pseudo-sword rolling across concrete. Hand scrabbling. Handle unsheathed. Muscle plunge. Clattering. Scrabbling — unsheathed — plunge — clattering. Scrabbling — unsheathed — plunge —

Someone was dead. His idea, however backward it had gone.

His.

Sweat fled his forehead. Fell to floorboards between his white runners. A faint pink residue still clung to the brand new rounds of rubber. From shoe to floorboard, imprint of dead boy blood.

Chris began a series of breathy hard-kicked hiccups, but struggled to swallow them, one by one, back down.

Outside the holding room, the hallway clock continued its parade of hesitant steps. If he knew a thing, what made him incapable of stopping it? Chris swallowed, swallowed, swallowed; each gulp chalked

it

up to a glitch.

PLAYER 2

Tammy sat down on the stool in front of the pushcart and rested short red-nailed fingers on the keys, tentatively, as though she might receive an electric shock. Blank grey TV face. The wood wall clock pointed its two arms in the same direction, the heart-shaped tin hands momentarily butterflied. The short one had almost hit XI, the long one at X. Ten minutes ’til

The Price is Right.

She reached around the televison’s back, found and flicked the switch box. She had time to try just a couple of things out.

The computer spoke, chunky-syllabled.

The arcade version of Berzerk had talked — blurted out, “Intruder Alert! Intruder Alert! Stop the humanoid!” Running from one room to another, the player attempted to shoot the robots before the all-powerful smiley face of Evil Otto appeared, effortlessly bounced through electrocuting walls in pursuit of the player. But by the time this audio made an impact on Tammy (at a Chuck E. Cheese in Michigan), she was intimate with Chris’s imitation of the machine. The machine original cried a mere imitation of her brother.

For a television to converse was something else entirely. The black ridges of its speaker mouth were usually a dumb portal, open to whatever actor’s voice had been tuned across its pixeled head. This thing that would normally blare Johnny Olson’s voice — his repetitive call of “Come on down! You’re the next contestant on

The Price is Right!”

— had suddenly found the ability to read aloud whatever Tammy typed onto its fluorescent face.