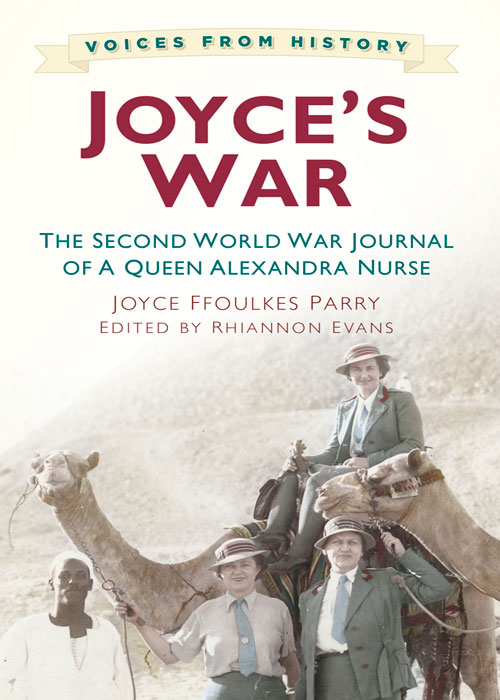

Joyce's War

Authors: Joyce Ffoulkes Parry

In memory of Joyce Ffoulkes Thomas (

née

Parry)

who inspired us all.

For her grandchildren:

Catrin, Owain, Lucy and Rhianwen

and her great-grandchildren

Tom, Ella, Oscar, Felix, Osian and Inigo

CONTENTS

Abbreviations Used in the Text

The Journal

1940 How little any of us suspected what lay before us

1941 Great speculation about what will become of us

1942 Strange how one becomes accustomed to a new mode of life

1943 Who can see the end of it all?

1944 Return to my native hills

With thanks to my sister Siân Bailey for her advice and support at all stages of this journey; to my brothers Ifor and Vaughan Davies, Peter Bailey and Graham McLean for their help, in particular for reading and commenting on the manuscript at its various stages and for helping to select and scan photos. Thanks also to Margaret Carleton at Edge Hill University who turned the early draft into a professional document.

Many thanks to Peter Bailey for the map illustration and Siân for the line drawings which so perfectly capture the mood of the journal.

I would also like to thank the editors at The History Press: Cate Ludlow for her enthusiasm from the beginning and Naomi Reynolds for her helpful advice and comments throughout.

I do want you to know that, whatever success I may attain and I have a cold, driving and ruthless ambition to make something of my life, I shall attribute it largely to you, because you, of all people, gave me something fresh and loyal and enduring.

The letter from which this extract is taken was received in January 1946; the war was over and Joyce Davies (

née

Parry) had been married for two years. She was living in Wales and I, the first of her four children, was a toddler. We will never know now the identity of its author but let’s call him Major X. He is not mentioned in Joyce’s journals and we do not know whether he ever received a reply because almost all of the hundreds of letters that Joyce and her family and friends exchanged during the war have disappeared. But we do know that it was written in response to a letter received from her at the end of 1945 and so we must assume that Major X was as significant a part of Joyce’s war as she was of his. He may have been a patient, a colleague or the young Medical Officer Pozner, the poet she refers to who was dispatched to the jungle in September 1942. This is one of the mysteries that lie at the heart of this journal and it points to the challenges in transcribing material many years after the person has died: you cannot ask the critical questions and you cannot check the names of friends, lovers or colleagues who may be recorded only by first name, surnames or nicknames. All of them will, in any case, almost certainly be dead. Joyce herself died in 1992, and, although the family was aware of the journal, it was not until I retired in 2009 that I set myself the task of transcribing the two blue vellum foolscap volumes which had lain with photograph albums and associated papers from the war in a deep drawer in the cupboard of her bedroom.

There are many published war journals of the great and famous but there are relatively few by women, and even fewer by nurses, whose contributions must sometimes seem invisible to the generations that have no direct links with the Second World War. Nursing or nurses are not listed in the index of Anthony Beevor’s recent and definitive

The Second World War

,

1

despite the critical role that they played. A few individual diaries of nurses’ wartime experiences have been published, although some are now out of print, and there are also edited composite accounts drawing on the letters and diaries of nurses on active service in the Middle East.

Joyce’s War

tells a unique story of a Queen Alexandra (QA) nurse who set out to make a record of the war, of her experiences and of the places she visited; in so doing and unintentionally she reveals a great deal about herself. In telling her own story she tells the story of countless other nurses who worked during their formative years on active service far away from home.

Joyce Ffoulkes Parry, the oldest of six children, was born in 1908 in Caerwys, a village in North Wales, and in 1911 at the age of 2 she emigrated with her parents and her baby brother Glyn to Australia. Her father had been appointed as a minister to a Presbyterian church, where he was required to preach sermons in English and Welsh. The family settled in a manse at Ballarat, which had become a thriving town made popular by the gold rush in 1850 and where 2,000 Welsh people were living. Four more children were born: Mona, Ifor, Clwyd and Wyn, but in the years that followed the family experienced great sadness with the loss of Wyn as a baby and the tragic drowning of Ifor aged 16. His death haunted Joyce all her life and we see in the journal her particular sensitivity to some of the very young wounded soldiers. The manse was a cultured and bookish household and Joyce won a scholarship as a boarder to Clarendon Ladies’ College, near Melbourne, where she excelled in English and history, winning all the major school prizes in her final years. Aged 18, after Highers, she began training to be a teacher but, following a row with her authoritarian father about her desire to read English at Melbourne University (where she had been awarded a partial scholarship), she undertook three years’ training as a nurse at Geelong Hospital, hoping it would lead to opportunities to travel. Upon registration she took up private nursing posts, including one with Major-General Robert Williams, who wrote to her throughout the war. The General, as he is referred to in the journal, was a well-known Australian military figure who had been a prominent editor and director of Australian newspapers.

With a romantic attachment to Wales, the country of her birth, Joyce sailed on HMS

Mongolia

back to Wales in February 1937. There she took up nursing posts and explored with her friend Mali and cousin Gwen the Welsh landscapes ‘of my beloved hills’ that she recalls with such longing when she is thousands of miles away. Following the declaration of war she registered in March 1940 as a QA Sister, which was an officer rank in the army. This gave her the opportunity she had longed for to travel as well as to make a useful contribution to the war; and also to write.

Her 75,000-word journal begins when she was 31, with a month in the summer of 1940 in France (the phoney war), supposedly en route to Palestine, and ends when she is 35, in February 1944, in India on the eve of sailing back to Wales to begin her married life. In those four intense years she served on the troopship HTS

Otranto

, the hospital ship HMHS

Karapara

and in land hospitals in Alexandria and Calcutta, spending many months at sea, which led her to write in 1942: ‘How heavenly to walk in a garden after so many months on a ship.’ With destinations often unknown, she and her colleagues endured difficult and uncertain conditions at sea and there were frequent rumours of air raids, mines and torpedoes. Despite this, mail from family and friends from all parts of the world would arrive; sometimes there was nothing for weeks and at others a backlog of scores of letters and books.

The ships called into and spent time in ports (often for repairs) in South Africa, Iraq, India and Egypt where she records living an independent, even rather luxurious, life in grand hotels, compared to her contemporaries in England. It was certainly almost impossible before the war, or in the post-war years, for women on modest salaries to have the variety of experiences that Joyce records. She was able to go to the theatre and cinema, to indulge in shopping for clothes and shoes, or later for exquisite items for her trousseau, and she was able to stay in decent hotels while on leave. Silk or fine woollen dresses were made up from vogue patterns by tailors on the side of the road, markets were visited and ancient temples or sites were explored. There was often a party or some sightseeing with newly made friends and sometimes the social rounds were all too much and so her poetry books provided her with the solace and solitary moments that she needed to think or to write.

Throughout the journal Joyce is conscious that she is making a record of the war as she experienced it. She records with a great sweep a single day’s events on 10 December 1941: ‘Two days ago Japan declared war … attacked the American fleet in Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, landed troops in Borneo, the Philippines, bombed Hong Kong and Singapore, surrounded Ocean, Swains, Midway and Wake islands and succeeded in getting Thailand to capitulate – all on the first day.’ She records the entry of each country into the war and charts their progress, noting the key positions of the Allies in the Middle East. With great concern she records the heavy casualties back in London or Coventry, following news on the beloved wireless. But she is also aware of what she perceives as government propaganda. After the ‘grim events’ of Singapore she comments: ‘Apparently the government believes that the public is possessed of a very low intelligence, if it cannot see through the padding and the inane and fatuous statements uttered daily on the air and in the press.’ Her own view of these events is unique: seen from heart of the action in the Middle East but always from the perspective of her twin allegiances to Great Britain and Australia, whose interests she keeps an eye on in the Pacific.

Her themes extend beyond the everyday account of living conditions on board ship, battles with the authorities about uniform, inadequate supplies for patients (they were often short of essentials) or her criticism of and frustration with the army, particularly in respect of pay: ‘Nothing paid into the bank for three months and then they send it to Malaya.’ She writes in great detail about the exotic places she was able to visit, capturing encounters with the local people but also moments of reflection, such as from her hospital room in the converted convent in Calcutta: ‘Such a lovely morning, as I sit here writing, my windows open to the lake – full of blurred reflections, a light breeze blowing. Coolies pad up and down, barefoot, on the path below carrying stones … a white-clad sister walks across from the wards, dazzling in the strong sunlight.’ Shot through her own writing are frequent quotations from poems that she loved and her appetite for the new books and literary journals sent to her by friends and family was prodigious. In April 1941, when evacuation of the hospital in Egypt was considered, she writes that she will definitely take her

Albatross Anthology

‘in case they don’t go in for poetry in German concentration camps!’

She loved India and was passionately on the side of Indian independence, which got her into trouble with many of her colleagues: ‘I’ve been lecturing some of the boys on the ward for talking nonsense about India,’ she says in December 1942. In a letter addressed from Fort William, Calcutta, in 1947, Major Ramchandani, Chief Medical Officer aboard the

Karapara

, wrote to thank her for being a loyal and staunch supporter of India and its independence.

Friendships and wartime camaraderie are a significant part of the wartime experience. Mona Stewart, who registered as a QA in London at the same time, is a constant companion and roommate up to 1942 when she is posted to Dehra Dun. Most other friends and colleagues are referred to by their surnames or forenames and in the dramatis personae I have tried to give information about some of the most frequently mentioned people. Despite her attempts to keep her feelings to herself, Joyce often writes about the frustration, the boredom and, towards the end of 1942, of her exhaustion: ‘I am tired these days and my brain is weary with running or trying to run the ward with 54 patients and one orderly to help me.’ While it is true that she does not allow herself much time for reflection on her personal life, her engagement is announced quite out of the blue and fourteen months later, somewhat cryptically, she records breaking it off with the words: ‘Another chapter closed and another begun.’