Joy of Home Wine Making (44 page)

Read Joy of Home Wine Making Online

Authors: Terry A. Garey

Tags: #Cooking, #Wine & Spirits, #Beverages, #General

To me, most grape rosés are kind of bland. They seem like watered-down reds or whites without much integrity, although of course there are exceptions.

Fruit rosé wines are much more interesting and produce some glorious rosés. When you think about it, most of the “reds” in this book are actually dark rosés. There is nothing bland about any of them. I feel they offer an exciting new dimention to wines in general.

Try using Freezer Rosé as a generic rosé, or try this recipe a.k.a. in our household as Pink Plonk. Feel free to adjust the fruit composition to suit your tastes. By all means, become a rosé enthusiast.

½ lb. fresh or frozen strawberries or raspberries

½ lb. fresh or frozen blueberries

1 12 oz. can frozen cran-raspberry drink

water sufficient to make up a gallon

1½ lbs. sugar or 2 lbs. light honey

1 tsp. acid blend

¼ tsp. tannin

1 tsp. yeast nutrient

1 Campden tablet, crushed

½ tsp. pectic enzyme

1 packet champagne yeast

Prepare the fruit and put it into a nylon straining bag. Mash the fruit with a sanitized potato masher or your very clean hands. Thaw the juice.

Boil about three quarts of the water and sugar or honey and pour the hot sugar water over the fruit and cran-raspberry juice. Add the rest of the water needed to make up the gallon. Add the yeast nutrient, tannin, and acid or lemon juice. Wait until the must cools down to add the Campden tablet, if you choose to use one. Cover and fit with an air lock. If you use the Campden tablet, wait at least 12 hours before adding the pectic enzyme. In another 12 to 24 hours, check the PA and add the yeast.

Stir daily. In a week or two, lift out the fruit bag and let it drain without squeezing before discarding the fruit. When the PA

goes down to 2 to 3 percent, rack off the wine into a glass carboy, and fit it with an air lock.

Rack the wine twice more during the next six months or so. Wait till the wine clears and it ferments out dry. You can sweeten this a little if you like, adding stabilizer and 2 to 4 ounces of sugar in a syrup. Bottle and sample in six months.

Fortified and Sparkling Wines

PORT

P

ort is a Portuguese red wine that has been fortified with Portuguese brandy up to about 20 percent alcohol and is properly called Porto. It has a long history and many imitators.

The original grape wine was harsh, dry, and it didn’t travel well. Brandy was added to stabilize it so it could be sweeter and longer-lived for shipping—a wonderful example of making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

Fine port is expensive but worth it if you have the money. Good port-type wines are made outside Portugal (such as those from California and Australia), but the best stuff comes from Portugal.

There are many different styles of port, from the young ruby port (no relation to Ruby Tuesday) to tawny port, to the vintage ports. Some people keep their port cellared for decades before

drinking it. It gets left to relatives in wills. Choose your ancestors carefully!

It is said that some cheaper ports and port-type wines have been “adulterated” with other fruits, such as elderberries, to fake the richness of true Porto.

You and I can’t make port. But we can make port-like wines that are pretty good!

Now that you know the characteristics of the dark fruit wines, you can use your imagination to mentally taste some combinations. Combinations of dark fruits do the best job of mimicking the rich complexity that is port. I like to use fresh or frozen fruit for the most part, though some dried fruits, such as elderberries and raisins, are good to add.

The addition of brandy or spirits also contributes to the flavor and body of the wine. Good brandy is better than cheap brandy for this purpose (big surprise, huh?), and really good brandy is wasted (whew). You can also use high-alcohol grain alcohol (120 to 140 proof) if you can get it in your area. You don’t need as much, and it doesn’t dilute the taste of the wine the way brandy does. Also, the addition of the alcohol kills off any leftover yeast, stabilizing the wine and allowing you to sweeten it if you choose.

Another means of fortification is to use flavored brandies. Commercial fruit brandies are frequently too sweet for my taste, and they are also low in alcohol, so I usually make my own, using high-alcohol grain spirits. Check out the Extra Helpings chapter on Chapter 12 for some simple recipes. It’s very easy to make your own fruit brandies using brandy, vodka, etc. as a base.

When making wine that you plan to fortify, try to use a wine yeast that allows a maximum amount of alcohol, if you can, and use the maximum amount of sugar you think you can get away with (up to 14, or even 15, percent). Port or sherry yeasts are best. The best method I have come up with for making these wines is to have a long, slow fermentation, ferment the wine out dry, and then fortify it.

You can tease the yeast into making more alcohol by adding controlled amounts of thick sugar syrup (two parts sugar to one part water) in very small doses during the secondary fermentation. This is called syrup feeding. (It is not necessary to call out “Sooeee, sooee, sooee, here yeast yeast yeast,” but you can if you are feeling particularly full of beans.)

As soon as the wine ferments out, add enough sugar syrup to bring the alcohol up a tiny bit, and let it ferment out again. Do this several times, then rack the wine and clear. This is where the Specific Gravity reading becomes really important, rather than merely the Potential Alcohol! You want to start out at 1.000 SG, and raise it only to 1.0900 or less, then ferment back to 1.000 again. Don’t try to put more than another pound of sugar into a gallon this way.

I find it hard to remember to monitor everything, so I usually take the expensive way out and get the highest alcohol content I can in the basic fermentation and fortify with alcohol.

PEARSON SQUARE

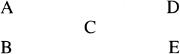

The Pearson Square is a useful tool depending on how good you are with math. Here is how it looks:

It’s very simple algebra.

A is the percent of alcohol in the spirit you are going to use to fortify your wine. (80 proof would be 40 percent alcohol, 120 proof is 60 percent. The “proof” is always twice the actual alcohol content.)

B is the alcohol content of the wine at hand (which you know from having kept track, right?).

C is the degree of fortification you want in the finished product.

D equals C minus B, and gives you the proportion of spirit to use.

E equals A minus C, or the proportion of the basic wine you need.

Or: A = C + E. B = C - D. C = B + D. D = C - B. E = A - C.

So, say A is 40 percent, and B is 12 percent, and C is 20 percent. Then D is 8 and E is 20, which indicates that some hefty fortifying is needed. That’s eight parts spirit to twenty parts wine in the finished product—an improbable 40 percent result, which will give a strong alcohol content and a weak taste at an expensive price.

So what happens if we start with wine with a higher percent, and alcohol with a higher percent? A is 60 percent, B is 15 per

cent, and C is still 20 percent. C minus B is 5 (D), and A minus C is 40 (E), which gives us five parts alcohol to forty parts wine, a 12 percent result, which is a lot better and a lot more drinkable.

BLUEBERRY PORTAGE

BLUEBERRY PORTAGE

5 lbs. blueberries

¼ lb. dried elderberries

2-4 ozs. banana flakes or ½ lb. dark raisins (optional)

sufficient water to make up a gallon

1¾ lbs. sugar or 2 lbs. honey, adding another ½ lb. later

½ tsp. acid blend

no tannin (the elderberries have plenty)

1 tsp. yeast nutrient

1 Campden tablet, crushed (recommended)

½ tsp. pectic enzyme

1 packet sherry, port, or Montrachet yeast

brandy, grain alcohol, or fruit brandy to fortify the result to the percentage you desire later

Pick over the berries carefully. Watch for mold. Discard anything that looks odd. Wash the berries in cool water, and drain. Soak the dried elderberries for a half hour in a cup of hot water. Drain the elderberries and reserve the water.

Wash your hands. Put the berries in a nylon straining bag and into the primary fermenter, then squash with your hands (you might want to use sanitized rubber gloves) or a sanitized potato masher. Be sure you press the berries well. Add the dried elderberries and (optional) banana flakes or raisins (these give even more body and flavor).

Boil the water and sugar or honey. Skim if necessary. Pour the hot sugar water over the crushed berries. You can chill and reserve half the water beforehand, adding it now to bring the temperature down quickly. Add the elderberry water, acid, and yeast nutrient, but wait until the temperature comes down to add the Campden tablet, if you choose to use one. Cover and fit with an air lock. Wait 12 hours to add the pectic enzyme.

Check the PA and write it down. You can adjust the PA up a bit at this point.

Twenty-four hours later, add the yeast. Stir it daily. Keep it a little warmer than usual, but not over 75°F. After about two weeks,

remove the bag (don’t squeeze). Discard the fruit. After the sediment has settled down again, check the PA. It will probably need to go another week. When it gets to 3 to 4 percent PA, rack the wine into your glass fermenter. Bung and fit with an air lock.

Add the extra half pound of sugar, dissolved in water, to the must gradually, watching the SG as described in Pearson Square. Make a note of it. If the beginning PA was higher than 14 percent, don’t add the sugar. The yeast may not take it. (The engines will na take it, Cap’n…)

Rack the wine at least twice during fermentation. You don’t want any off flavors. Be sure to keep it in a dark jug, or put something over it to keep the light from stealing the color.

In six to eight months, or even more, check the PA, and judge the clarity. Taste it, too. There should be plenty of tannin from the elderberries—maybe what seems to be too much. Do you think it will gain in smoothness and flavor over the next couple of years? Here you have to decide if you want to go to the expense of adding the grain alcohol, the brandy, or the fruit brandy.

To be accurate, use the Pearson Square to figure out how much alcohol, of what proof, you will need to bring it up to 19 or 20 percent. If that gives you a headache, figure about two to three cups of 80 proof brandy to the gallon. You might want to add some sugar syrup, too, so add four to six ounces dissolved in water. The alcohol will kill off the yeast, so you don’t have to worry about the additional sugar.