Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) (5 page)

Read Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Online

Authors: Jules Verne

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

8.29Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

When I add that my uncle walked in mathematical strides of half a fathom, and if I point out that in walking he kept his fists firmly clenched, a sure sign of an irritable temperament, it will be clear enough that his company was something less than desirable.

He lived in his little house in the Königstrasse, a building made half of brick and half of wood, with a stepped gable; it overlooked one of those winding canals that intersect in the middle of Hamburg’s old town, which the great fire of 1842 had fortunately spared.

The old house leaned a little, admittedly, and bulged out towards the street; its roof sloped a little to one side, like the cap over the ear of a Tugendbund student;

b

its verticality left something to be desired; but overall, it held up well, thanks to an old elm which buttressed it in front, and which in spring pushed its flowering branches through the window panes.

b

its verticality left something to be desired; but overall, it held up well, thanks to an old elm which buttressed it in front, and which in spring pushed its flowering branches through the window panes.

My uncle was reasonably well off for a German professor. The house was all his own, container and contents. The contents consisted of his god-daughter Graüben,

2

a seventeen-year-old from Virland,

c

Martha, and myself. As his nephew and an orphan, I became his laboratory assistant.

2

a seventeen-year-old from Virland,

c

Martha, and myself. As his nephew and an orphan, I became his laboratory assistant.

I admit that I plunged eagerly into the geological sciences; I had the blood of a mineralogist in my veins, and never got bored in the company of my precious rocks.

In a word, one could live happily in the little house in the Königstrasse, in spite of the impatience of its master, for even though he showed it in a somewhat rough fashion, he was nevertheless very fond of me. But that man was unable to wait, and nature herself was too slow for him.

In April, after he had planted seedlings of mignonette and morning glory in the clay pots in his living-room, he would go every morning and tug them by their leaves to accelerate their growth.

Faced with such a character, one could do nothing other than obey. I therefore rushed after him into his study.

II

THIS STUDY WAS A genuine museum. Specimens of everything known in mineralogy lay there labeled in the most perfect order, according to the great divisions into inflammable, metallic, and lithoid minerals.

How well I knew all these bits of mineralogical science! How many times, instead of enjoying the company of boys of my own age, had I enjoyed dusting these graphites, anthracites, coals, lignites, and peats! And the bitumens, resins, organic salts that needed to be protected from the least atom of dust! And these metals, from iron to gold, whose current value disappeared in the absolute equality of scientific specimens! And all these stones, enough to rebuild the house in the Königstrasse, even with a handsome additional room, which would have suited me admirably!

But on entering this study, I barely thought of all these wonders. My uncle alone filled my thoughts. He had thrown himself into an armchair covered with Utrecht velvet, and held in his hands a book that he contemplated with the profoundest admiration.

“What a book! What a book!” he exclaimed.

This exclamation reminded me that my uncle was also a bibliophile in his moments of leisure; but an old book had no value in his eyes unless it was very difficult to find or at least illegible.

“Well!” he said to me, “don’t you see? Why, this is a priceless treasure that I found this morning browsing in Hevelius the Jew’s shop.”

“Magnificent!” I replied, with an enthusiasm made to order.

But actually, what was the point of all this fuss about an old quarto, apparently bound in rough calfskin, a yellowish volume with a faded seal hanging from it?

Nonetheless, there was no end to the professor’s admiring exclamations.

“Look,” he went on, both asking the questions and supplying the answers. “Isn’t it a beauty? Yes; admirable! Did you ever see such a binding? Doesn’t this book open easily? Yes, because it remains open anywhere. But does it shut equally well? Yes, because the binding and the leaves are flush, all in a straight line, with no gaps or separations anywhere. And look at this spine, which doesn’t show a single crack even after seven hundred years! Why, Bozerian, Closs, or Purgold

d

might have been proud of such a binding!”

d

might have been proud of such a binding!”

As he was speaking, my uncle kept opening and shutting the old tome. I really could do no less than ask a question about its contents, although it did not interest me in the least.

“And so what’s the title of this marvelous work?” I asked with an eagerness so pronounced that it had to be fake.

“This work,” replied my uncle with renewed enthusiasm, “is the

Heims Kringla

of Snorre Turleson, the famous Icelandic author of the twelfth century!

e

It’s the chronicle of the Norwegian princes who ruled in Iceland.”

Heims Kringla

of Snorre Turleson, the famous Icelandic author of the twelfth century!

e

It’s the chronicle of the Norwegian princes who ruled in Iceland.”

“Really!” I exclaimed, with my best effort, “and of course it’s a German translation?”

“What!” replied the professor sharply, “a translation! And what would I do with a translation? Who cares about a translation? This is the original work in Icelandic, that magnificent language, rich and simple at the same time, which allows for an infinite variety of grammatical combinations and multiple word modifications!”

“Like German,” I skillfully remarked. “Yes,” replied my uncle, shrugging his shoulders; “but in addition Icelandic has three genders like Greek, and declensions of nouns like Latin.”

“Ah!” I said, a little shaken in my indifference; “and is the typeface beautiful?”

“Typeface! What do you mean by typeface, wretched Axel? Type! As if it were a matter of typeface! Ah! do you think this a printed book? But, ignorant fool, this is a manuscript, and a Runic

f

manuscript at that!”

f

manuscript at that!”

“Runic?”

“Yes! Are you going to ask me now to explain that word to you?”

“Of course not,” I replied in the tone of a man whose self-esteem has been hurt.

But my uncle persevered anyway, and told me, against my will, about things that I did not care to know.

“Runes,” he explained, “were characters once used in Iceland, and according to legend, they were invented by Odin himself. So look at this, impious young man, and admire these letters created by the imagination of a god!”

Well, not knowing what to say, I was going to prostrate myself before this wonderful book, a way of answering equally pleasing to gods and kings, because it has the advantage of never giving them any embarrassment, when a little incident happened to turn the conversation into another direction.

It was the appearance of a dirty slip of parchment which slipped out of the volume and fell to the floor.

My uncle pounced on this shred with understandable eagerness. An old document, hidden for time immemorial in an old book, inevitably had an immeasurable value for him.

“What’s this?” he exclaimed.

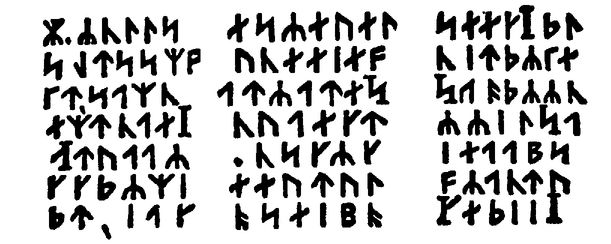

And at the same time, he carefully spread on the table a piece of parchment, five inches by three, which was covered with horizontal lines of illegible characters.

Here is the exact facsimile. It is important to me to let these bizarre signs be publicly known, for they incited Professor Lidenbrock and his nephew to undertake the strangest expedition of the nineteenth century.

My uncle pounced on this shred with understandable eagerness.

The professor mused a few moments over this series of characters; then he said, raising his spectacles:

“These are Runic letters; they are identical to those of Snorre Turleson’s manuscript. But what could they possibly mean?”

Since Runic letters seemed to me an invention of the learned to mystify this poor world, I was not sorry to see that my uncle did not understand them. At least, it seemed that way to me, judging from the movement of his fingers, which began to tremble violently.

“But it’s certainly old Icelandic!” he muttered between his teeth.

And Professor Lidenbrock should know, for he was considered a genuine polyglot. Not that he could speak all two thousand languages and four thousand dialects which are spoken on the earth, but he did know his share of them.

And so, faced with this difficulty, he was going to give way to all the impetuosity of his character, and I was anticipating a violent outbreak, when two o’clock struck on the little timepiece over the fireplace.

Immediately, the housekeeper Martha opened the study door and said:

“Dinner is ready!”

“To hell with dinner!” shouted my uncle, “and the one who prepared it, and those who will eat it!”

Martha fled. I followed her, and hardly knowing how I got there, I found myself seated at my usual place in the dining-room.

I waited a few moments. The professor did not come. This was, to my knowledge, the first time he had ever missed the ritual of dinner. And yet what a dinner it was! Parsley soup, ham omelet garnished with spiced sorrel, fillet of veal with compote of prunes, and for dessert, sugared shrimp, the whole washed down with a nice Moselle wine.

All this my uncle was going to sacrifice to a bit of old paper. Well, as a devoted nephew I considered it my duty to eat for him as well as for myself. That I did conscientiously.

“I’ve never seen such a thing,” said Martha the housekeeper. “Mr. Lidenbrock not at table!”

“Who could believe it?”

“This means something serious is going to happen,” said the old servant, shaking her head.

In my opinion, it meant nothing more serious than an awful scene when my uncle discovered that his dinner had been devoured.

I had come to my last shrimp when a stentorian voice tore me away from the pleasures of dessert. With one leap I bounded out of the dining-room into the study.

III

“IT’S OBVIOUSLY RUNIC,” SAID the professor, knitting his brows. “But there’s a secret here, and I’ll discover it, or else ...”

A violent gesture finished his thought.

“Sit there,” he added, pointing with his fist at the table, “and write.”

I was ready in an instant.

“Now I’ll dictate to you every letter of our alphabet which corresponds with one of these Icelandic characters. We’ll see what that will give us. But, by St. Michael! Take care that you don’t make mistakes!”

The dictation began. I did my best. Every letter was called out one after the other, and resulted in the unintelligible sequence of the following words:

| mm.rnlls | esreuel | seecJde |

| sgtssmf | unteief | niedrke |

| kt,samn | atrateS | Saodrrn |

| emtnael | nuaect | rrilSa |

| Atvaar | .nscrc | ieaabs |

| ccdrmi | eeutul | frntu |

| dt,iac | oseibo | KediiY |

When this work was ended, my uncle quickly took the paper on which I had been writing, and examined it attentively for a long time.

“What does this mean?” he kept repeating mechanically.

On my honor, I could not have enlightened him. Besides he did not question me, and went on talking to himself.

“This is what we call a cryptogram,” he said, “where the meaning is hidden under deliberately scrambled letters, which in their proper order would result in an intelligible sentence. When I think that there’s perhaps the explanation or clue to some great discovery here!”

As far as I was concerned, there was absolutely nothing in it, but of course, I took care not to reveal my opinion.

Then the professor took the book and the parchment, and compared them with one another.

“These two writings are not by the same hand,” he said; “the cryptogram is of a later date than the book, and I see one irrefutable proof of that. The first letter is actually a double m, a letter which can’t be found in Turleson’s book because it was only added to the Icelandic alphabet in the fourteenth century. So there are at least two hundred years between the manuscript and the document.”

Other books

Tears of the Neko by Taylor Ryan

THE PRIZE: BOOK TWO - RETRIBUTION by Rob Buckman

The Sea Runners by Ivan Doig

The Memory Jar by Tricia Goyer

What Evil Lurks in Monet's Pond: A by Barton, Sara M.

Heaven and Mel (Kindle Single) by Joe Eszterhas

Winter Duty by E. E. Knight

Solbidyum Wars Saga 9: At What Price by Dale Musser

Lighter Shades of Grey by Cassandra Parkin

Heaven's Fire by Sandra Balzo