Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) (28 page)

Read Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Online

Authors: Jules Verne

BOOK: Journey to the Center of the Earth (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

3.3Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

But my uncle quickly regained control of himself.

“Ah! Fate plays these tricks on me!” he exclaimed. “The elements conspire against me! Air, fire and water join their efforts to oppose my journey! Well then! They’ll find out what my will power is made of. I will not yield, I will not take a single step backwards, and we’ll see whether man or nature wins out!”

Standing on the rock, enraged, threatening, Otto Lidenbrock seemed to challenge the gods like the fierce Ajax.

bp

But I thought it appropriate to intervene and restrain this irrational energy.

bp

But I thought it appropriate to intervene and restrain this irrational energy.

“Listen to me,” I said to him in a firm voice. “There’s a limit to ambition down here; we can’t struggle against the impossible. We’re ill-equipped for another sea voyage; one can’t travel five hundred leagues on a paltry assemblage of wood beams, with a blanket for a sail, a stick for a mast, and the winds unleashed against us. We cannot steer, we’re a plaything for the storms, and it’s madness to attempt this impossible crossing for a second time!”

I was able to unfold this series of irrefutable reasons for ten minutes without being interrupted, but only because of the inattention of the professor, who did not hear a word of my arguments.

“To the raft!” he shouted.

That was his reply. It was no use begging him or flying into a rage, I was up against a will harder than granite.

Hans was finishing up the repairs of the raft at that moment. One would have thought that this strange being guessed my uncle’s plans. He had reinforced the vessel with a few pieces of surturbrand. He had already hoisted a sail in whose folds the wind was playing.

The professor said a few words to the guide, and immediately he put everything on board and arranged everything for our departure. The air was rather clear, and the north-west wind blew steadily.

What could I do? Stand alone against the two of them? Impossible. If only Hans had taken my side. But no! The Icelander seemed to have given up any will of his own and to have made a vow of self-denial. I could not get anything out of a servant so beholden to his master. I had to go along.

I was therefore about to take my usual place on the raft when my uncle stopped me with his hand.

“We won’t leave until tomorrow,” he said.

I made the gesture of a man who is resigned to anything.

“I must not neglect anything,” he resumed; “and since fate has driven me to this part of the coast, I won’t leave it until I’ve explored it.”

To understand this remark, one must know that we had come back to the north shore, but not to the exact point of our first departure. Port Graüben must have been further to the west. Therefore, nothing more reasonable than to explore carefully the surroundings of this new landing spot.

“Let’s go on discovery!” I said.

And leaving Hans to his activities, we started off together. The space between the water and the foot of the cliffs was considerable. It took us half an hour to get to the wall of rock. Our feet crushed innumerable shells of all shapes and sizes in which the animals of the earliest ages had lived. I also saw enormous turtle shells that were more than fifteen feet in diameter. They had belonged to those gigantic glyptodonts of the Pliocene period,

bq

of which the modern turtle is but a small reduction. The ground was in addition strewn with a lot of stone fragments, shingles of a sort that had been rounded by the waves and arranged in successive lines. This led me to the remark that at one time the sea must have covered this ground.

bq

of which the modern turtle is but a small reduction. The ground was in addition strewn with a lot of stone fragments, shingles of a sort that had been rounded by the waves and arranged in successive lines. This led me to the remark that at one time the sea must have covered this ground.

On the scattered rocks, now out of their reach, the waves had left manifest traces of their passage.

This might up to a point explain the existence of this ocean forty leagues beneath the surface of the globe. But in my opinion this liquid mass had to be gradually disappearing into the bowels of the earth, and it obviously had its origin in the waters of the ocean overhead, which had made their way here through some fissure. Yet it had to be conceded that this fissure was now stopped up, because this entire cavern, or better, this immense reservoir had filled up in a relatively short time. Maybe the water, struggling against the subterranean fire, had even partly evaporated. That would explain the clouds suspended over our heads and the discharge of the electricity that gave rise to tempests in the interior of the earth.

This theory of the phenomena we had witnessed seemed satisfactory to me; for however great the wonders of nature may be, they can always be explained by physical causes.

We were therefore walking on a kind of sedimentary terrain, deposited by water like all the soils of that period, of which there are so many across the globe. The professor examined every fissure in the rock carefully. Wherever an opening showed, it was important to him to probe its depth.

br

br

We had walked along the shores of the Lidenbrock Sea for a mile when soil suddenly changed in appearance. It seemed turned upside down, convulsed by a violent upheaval of the lower strata. In many places depressions or elevations testified to a powerful displacement of the earth’s substance.

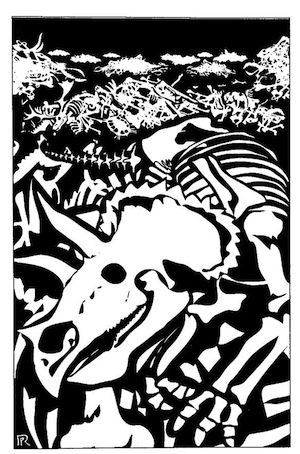

We were moving with difficulty across these cracks of granite mixed with flint, quartz, and alluvial deposits, when a field, more than a field, a plain of bones appeared before our eyes. One would have thought it was an immense graveyard, where the generations of twenty centuries mingled their eternal dust. Tall mounds of residue stretched away into the distance. They undulated to the limits of the horizon and vanished into a hazy mist. Here, in perhaps three square miles, the complete history of animal life was piled up, a history that has hardly yet been written in the too recent strata of the inhabited world.

But an impatient curiosity drove us on. With a dry noise, our feet crushed the remains of these prehistoric animals, fossils over whose rare and interesting residues the museums of great cities fight. A thousand Cuviers would not have been enough to reconstruct the skeletons of the organic beings lying in this magnificent boneyard.

I was stunned. My uncle had lifted his long arms to the massive vault that served us as sky. His mouth gaping wide, his eyes flashing behind the glass of his spectacles, his head moving up and down, from left to right, his whole posture indicated infinite amazement. He stood facing an invaluable collection of leptotheria, mericotheria, lophiodons, anoplotheria, megatheria, mastodons, protopithecae, pterodactyls, of all the prehistoric monsters, piled up for his personal satisfaction. Imagine an enthusiastic bibliophile suddenly transported to the famous library of Alexandria that was burned by Omar, and which by a miracle had been reborn from its ashes! That was my uncle, Professor Lidenbrock.

But it was a very different amazement when, running across this organic dust, he seized a bare skull and shouted with a trembling voice:

“Axel! Axel! a human head!”

“A human head!” I exclaimed, no less astonished.

“Yes, nephew. Ah! Mr. Milne-Edwards! Ah! Mr. de Quatrefages,

bs

I wish you were standing here where I, Otto Lidenbrock, am standing!”

bs

I wish you were standing here where I, Otto Lidenbrock, am standing!”

The complete history of animal life was piled up.

XXXVIII

TO UNDERSTAND MY UNCLE’S invocation of these illustrious French scholars, one must know that an event of great importance for paleontology had occurred some time before our departure.

On March 28,1863, some excavators working under the direction of Mr. Boucher de Perthes, in the stone quarries of Moulin Quignon, near Abbeville, in the department of the Somme in France, found a human jawbone fourteen feet beneath the surface. It was the first fossil of its kind that had ever been unearthed. Nearby stone hatchets and flint arrow-heads were found, stained and coated with a uniform patina by the ages.

8

8

The repercussions of this discovery were great, not in France alone, but in England and in Germany. Several scholars of the French Institute, among others Messrs. Milne-Edwards and de Quatrefages, took the affair very seriously, proved the irrefutable authenticity of the bone in question, and became the most ardent advocates in this ‘trial of the jawbone,’ as it was called in English.

Geologists of the United Kingdom who considered the fact as certain—Messrs. Falconer, Busk, Carpenter,

9

and others—were soon joined by scholars from Germany, and among them, in the first rank, the most energetic, the most enthusiastic, was my uncle Lidenbrock.

9

and others—were soon joined by scholars from Germany, and among them, in the first rank, the most energetic, the most enthusiastic, was my uncle Lidenbrock.

The authenticity of a human fossil from the Quaternary epoch

bt

therefore seemed to be irrefutably proven and admitted.

bt

therefore seemed to be irrefutably proven and admitted.

This theory, to be sure, encountered a most obstinate opponent in Mr. Élie de Beaumont.

bu

This scholar, a great authority, maintained that the soil of Moulin Quignon did not belong to the “diluvium” ‡ but to a more recent layer and, agreeing with Cuvier, he refused to admit that the human species had been contemporary with the animals of the Quaternary epoch. My uncle Lidenbrock, in agreement with the great majority of geologists, had stood his ground, disputed, and argued, until Mr. Élie de Beaumont had remained almost alone on his side.

bu

This scholar, a great authority, maintained that the soil of Moulin Quignon did not belong to the “diluvium” ‡ but to a more recent layer and, agreeing with Cuvier, he refused to admit that the human species had been contemporary with the animals of the Quaternary epoch. My uncle Lidenbrock, in agreement with the great majority of geologists, had stood his ground, disputed, and argued, until Mr. Élie de Beaumont had remained almost alone on his side.

We knew all the details of this affair, but we were not aware that since our departure the question had made further progress. Other identical jawbones, though they belonged to individuals of various types and different nations, were found in the loose grey soil of certain caves in France, Switzerland, and Belgium, along with weapons, utensils, tools, bones of children, adolescents, adults and old people. The existence of Quaternary man was therefore receiving more confirmation every day.

And that was not all. New remains exhumed from Tertiary Pliocene soil had allowed even bolder geologists to attribute an even greater age to the human race. These remains, to be sure, were not human bones, but products of his industry that carried the mark of human work, such as shin and thigh bones of fossil animals with regular grooves, sculpted as it were.

Thus, with one leap, man moved back on the time scale by many centuries. He preceded the mastodon; he was a contemporary of

elephas meridionalis;

bv

he lived a hundred thousand years ago, since that is the date that the most famous geologists give for the formation of Pliocene soil.

elephas meridionalis;

bv

he lived a hundred thousand years ago, since that is the date that the most famous geologists give for the formation of Pliocene soil.

Such, then, was the state of paleontological science, and what we knew of it was enough to explain our attitude toward this boneyard on the Lidenbrock Sea. It is therefore easy to understand my uncle’s amazement and joy when, twenty yards further on, he found himself in the presence of, one might say face to face with, a specimen of Quaternary man.

It was a perfectly recognizable human body. Had some special kind of soil, like that of the St. Michel cemetery in Bordeaux, preserved it like this over the centuries? I do not know. But this corpse, with its tight, parchment-like skin, its limbs still soft—at least on sight—intact teeth, abundant hair, frighteningly long finger and toe nails, presented itself to our eyes just as it was when it had been alive.

I was speechless when faced with this apparition of another age. My uncle, usually a talkative and impetuous speaker, also kept silent. We had lifted the body. We had raised it up. It looked at us with its empty eye-sockets. We touched its resonant torso.

After a few moments of silence, the uncle was overcome by Professor Otto Lidenbrock again who, carried away by his temperament, forgot the circumstances of our journey, the place where we were, the enormous cave that surrounded us. No doubt he thought he was at the Johanneum, lecturing to his students, for he assumed a learned voice and addressed an imaginary audience:

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I have the honor of introducing a man of the Quaternary period to you. Eminent scholars have denied his existence, others no less eminent have affirmed it. The St. Thomases of paleontology, if they were here, would touch him with their fingers, and would be forced to acknowledge their error. I am quite aware that science has to be on its guard with discoveries of this kind. I know how Barnum and other charlatans of the same ilk have exploited fossil men.

bw

I know the story of Ajax’ kneecap, the alleged body of Orestes found by the Spartans, and of the ten-cubit tall body of Asterius mentioned by Pausanias. I’ve read the reports on the skeleton of Trapani, discovered in the fourteenth century, which was at the time identified as that of Polyphemus, and the history of the giant unearthed in the sixteenth century near Palermo. You know as well as I do, gentlemen, the analysis of large bones carried out at Lucerne in 1577, which the famous Dr. Felix Plater declared to be those of a nineteen-foot tall giant. I have devoured the treatises of Cassanion, and all those dissertations, pamphlets, speeches, and rejoinders published respecting the skeleton of Teutobochus, king of the Cimbrians and invader of Gaul, dug out of a sandpit in the Dauphiné in 1613! In the eighteenth century I would have fought with Pierre Campet against the pre-adamites of Scheuchzer.

10

In my hands I have a text called Gigan—”

bw

I know the story of Ajax’ kneecap, the alleged body of Orestes found by the Spartans, and of the ten-cubit tall body of Asterius mentioned by Pausanias. I’ve read the reports on the skeleton of Trapani, discovered in the fourteenth century, which was at the time identified as that of Polyphemus, and the history of the giant unearthed in the sixteenth century near Palermo. You know as well as I do, gentlemen, the analysis of large bones carried out at Lucerne in 1577, which the famous Dr. Felix Plater declared to be those of a nineteen-foot tall giant. I have devoured the treatises of Cassanion, and all those dissertations, pamphlets, speeches, and rejoinders published respecting the skeleton of Teutobochus, king of the Cimbrians and invader of Gaul, dug out of a sandpit in the Dauphiné in 1613! In the eighteenth century I would have fought with Pierre Campet against the pre-adamites of Scheuchzer.

10

In my hands I have a text called Gigan—”

Other books

Lodestone Book One: The Sea of Storms by Mark Whiteway

Playing with Passion Theta Series Book 1 by Gayle Parness

Cities I've Never Lived In: Stories by Sara Majka

Scholar: A Novel in the Imager Portfolio by L. E. Modesitt

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Leonidovich Pasternak

The Blackmailed Bride by Kim Lawrence

Star Force: Evacuation (SF50) by Jyr, Aer-ki

Gemini (The Erotic Zodiac Book 2) by Livia Lang

Infinite Repeat by Paula Stokes

Missing Brandy (A Fina Fitzgibbons Brooklyn Mystery Book 2) by Susan Russo Anderson