Journey Between Worlds (7 page)

Read Journey Between Worlds Online

Authors: Sylvia Engdahl

I lay back and fixed my eyes on the rivets in the ceiling, wondering if they would broadcast the countdown. On a plane you can at least see what's happening; they retract the boarding tube, taxi out to the runway, and so forth. In this ship there was nothing to watch. Any minute, I could be pinned to the couch by goodness knows how many g's of acceleration.

The seat next to me was empty. “It was reserved,” the flight attendant said, “but the lady must have changed her mind at the last moment.”

“She may show up yet,” Dad said.

“It's too late now; we've sealed the airlock.”

“Sealed” had a very permanent sound. I was thinking that the holder of that seat had shown a good deal of sense, when the young man whose lunch table we had shared appeared at the hatch. He came directly toward us and sat down beside me. “Hi,” he said. “I heard there was an empty seat up here, and since you weren't in the compartment belowâ”

“Would you like your book?” I asked him. “My things are fastened down under here, but I guess there's time for me to get it. They won't weigh us any more, will they?”

“No, but don't bother now,” he said. He reddened, for a moment losing the air of cool confidence. “Say, I hope you don't think that's why I came up!”

I shook my head, not knowing what to say.

He went on, smiling, “I wanted to know more about you, that's all. Are you a university student? Biology? Geology?”

“Not yet. Not on Mars, I won't be.”

“Then how did they happen to let you emigrate? You're at least sixteen, so you can't be with homesteading parentsâ”

“I'm not an

emigrant,

” I told him hastily. “Dad and I are on a trip. For his firm.”

emigrant,

” I told him hastily. “Dad and I are on a trip. For his firm.”

His eyes questioned the way in which I'd emphasized

“emigrant”

as if it were a category in which I'd hate to be placed. But then they lit up again. “I was sure you were something special,” he said. “That is, I didn't think you could have the experience for a nonresident job on Mars; the career people we get are older.”

“emigrant”

as if it were a category in which I'd hate to be placed. But then they lit up again. “I was sure you were something special,” he said. “That is, I didn't think you could have the experience for a nonresident job on Mars; the career people we get are older.”

“We?”

“The Colonies. I'm a Colonial citizen; I was born on Mars. My home's in the city of New Terra. By the way, I'm Alex Preston.”

“And I'm Melinda Ashley.” I was staring at him again. I simply couldn't think of Alex as a Martian! He wasn't any different from anyone else. Well, hardly any different; there were those few little things I'd noticed, but there wasn't anything Martian about those differences. Not that I could have said just what I thought Colonials would be like.

The music stopped and the intercom burst out again, evidently a recording this time.

“We are now beginning the final two minutes of countdown. Liftoff minus one hundred twenty seconds . . . one hundred second . . .”

“We are now beginning the final two minutes of countdown. Liftoff minus one hundred twenty seconds . . . one hundred second . . .”

Alex buckled his straps with quick, practiced fingers and got his seat reclined just as the flight attendant hurried over for a last check before taking her own position. I glanced at Dad; his eyes were closed and there was a big smile on his face.

“Eighty seconds . . . sixty . . . fifty . . .”

Alex leaned over and touched my hand. “Why so quiet, Melinda? You're too solemn!”

“Forty . . . thirty . . .”

“Oh, I was just wondering what on earth I'm doing aboard this spaceship,” I said. My voice sounded terribly tragic, I think.

He laughed. Then suddenly I did too, at the utter inappropriateness of the idiom, and when liftoff hit us we were both still laughing.

That was the second time I surprised myself with Alex. There were lots more times to come.

Part Two

SPACE

Chapter 5

Right from the beginning Alex was a person that I could talk to. I've never been a talkative person; that's one reason I'm shy and find it hard to make friends. I never know what to say to people. Even Dad and I never had a great deal to say to each other, which was too bad considering how much we both wanted to be close. But with Alex it was different. He always came out with something that I just naturally replied to, or at any rate something interesting enough to make me content with listening. Alex and I had more real conversations during the trip to Mars alone than Ross and I had had during the whole time we were dating. It seemed funny, because I was in love with Ross, while Alex was just someone I met boarding a ship.

The acceleration that accompanied liftoff wasn't really very bad (though I wouldn't want to go through it too often). I felt somewhat woozy and relaxed from the shots, but I don't think I would have panicked anyway. The worst part was the immobile, helpless feeling more than the actual pressure: the feeling of being unable to stir, to draw a deep breath, even. And the awful, ear-shattering noise! But those things didn't last long. Besides, there was Alex next to me, and I couldn't help but find comfort in the thought that he'd been through this before. Why that seemed more significant than the simple fact that shiploads of people did it every day, I couldn't imagine.

When the rockets cut off we went right into zero gravity, and it felt as if the bottom had dropped out of everythingâwhich was exactly what had happened because there wasn't any “bottom” or “top” anymore. Zero-g has sometimes been called “free fall” and that's literally true, for it doesn't make any difference that the fall's not toward Earth, but away from it. This condition affects human beings in various ways. Some people love it; it's the kind of floating that used to be possible only in dreams. Others are just plain sick, and this would include a pretty large group if it weren't for those antinausea shots. Still others are terrifiedâafter all, as I learned in Psychology I, fear of falling's one of the two basic fears a baby's born withâand I suspect that I would have come out in the latter category, except that Alex didn't let me.

He raised his seat, then started to undo his straps so that he could reach over and raise mine. The flight attendant rushed right over and started to protest. (She floated through the hatch upside down, as it happenedâno wonder their uniforms have pants instead of skirtsâand turned so that her feet pointed toward the “floor” more for the passengers' benefit than for any practical reason.) “Sir, passengers are not allowed toâ”

Alex pulled his card wallet out of his pocket. “Even with this?” he inquired, holding something out to her.

“Sorry, Mr. Preston. Certainly you may unstrap.”

I looked at him and asked, tactlessly maybe, “Are you a VIP or something?”

He smiled. “Not at all. It's just that I have a card to show that I know how to handle myself in zero-g.” He released the lock on my seat and it sprang forward so that I was sitting up. “It used to be that they wouldn't let anyone unstrap on these short hauls, but as the proportion of experienced space travelers grew, so did the protests. Now they honor the cards. I'm afraid that won't help you or your dad, though.”

“I don't want to move around!” I declared fervently.

“I won't argue because they aren't going to let you anyway. But you'd be surprised at how much fun it is once you get a taste of it.”

“Where did you learn?” I asked. “You're not an astronaut, are you?”

“No. I learned on a trip to Phobos, when I was twelve. All Colonial kids do.”

“For fun?”

“Partly. You might call it a compensation for the centrifuge, which isn't so pleasant.”

“Centrifuge, like the way they test astronauts? Why did you have to do that if you weren't going to be one?”

“Because I knew that I might want to come to Earth someday. And Earth's gravity is three times what I was born to.” He grinned at me. “If I hadn't trained for it, Earth to me would have been something like that liftoff was to you.”

Slowly I took this in. I'd known Martian gravity was low, but the implications hadn't struck me before. No wonder he'd moved slowly and deliberately back at the terminal. “How could you train for it?” I asked.

“In a special gym, under spin. Ever since eighth grade, an hour a day. You work up gradually, of course. It prepares you to accept terrestrial gravity, but not to enjoy it. This is the first time I've been really comfortable since I landed last year!”

“I'm glad I wasn't born on Mars.”

“That's one way of looking at it,” he agreed. “But if you had been, you wouldn't have had to come to Earth; lots of people don't. It used to be that most families wanted their kids to go sooner or later, the way the early American colonists sent their sons home to England to be educated. But that attitude's getting to be old-fashioned.”

“You're not sorry you came, are you?”

“No, I wouldn't have missed it for anything. I could have gotten my master's degree just as well on Mars, I suppose. But I wouldn't have seen as much.”

“I should think,” I said hesitantly, “that now you've had a chance to live normallyâwell, that it would be awfully hard for you to go back, if it weren't for the gravity, that is. I mean, it might be better for you if you hadn't come.”

Alex stiffened. “What do you mean?”

“Well, you wouldn't have known what you were missing. That is, you'd have known, but you probably wouldn't have cared in the same way.” I was struggling with what was, for me, an unfamiliar concept. It was hard to imagine anybody regretting having come to Earth; yet for someone who'd been born a Martian, it must be terribly upsetting to come knowing that he couldn't stay long.

But Alex didn't understand me. “Perhaps I've given a wrong impression,” he said quietly. “Melinda, I was kidding about not getting used to Earth gravity! I could have, of course, if I'd had any reason for wanting to stay.”

I was confused, and sorry that I'd allowed the conversation to get so personal. It was none of my business why he was going back to Mars; perhaps his family needed him, or maybe he had run out of money and couldn't get a job. He wasn't a citizen of any country on Earth, after all.

He went on, “You're assuming quite a lot, aren't you, thinking that I'd be happier on Mars if I hadn't seen Earth?” There was a sharp tone in his voice; without meaning to, I'd somehow made him angry.

By that time all I wanted to do was drop the subject, but I asked, “What am I assuming?”

We were interrupted by the flight attendant who, much to my relief, had come to serve tea. The spacelines operate on the same theory as the airlines used to, which is that passengers will cause less trouble, and will think that they're getting more for their money, if they are kept constantly occupied with something to eat. Or maybe they feel that if anyone's nervous, the sight of other people eating will seem reassuring; and that's probably true. At any rate, in spite of its being just after lunch by Florida time and the middle of the night by Greenwich, we were offered a bountiful selection of such goodies as could be adapted to zero-g conditions, as well as our choice of coffee, tea, or soft drinks. The beverages came in closed containers with sipping tubes, for you can't pour a liquid that's weightless; you've got to suck.

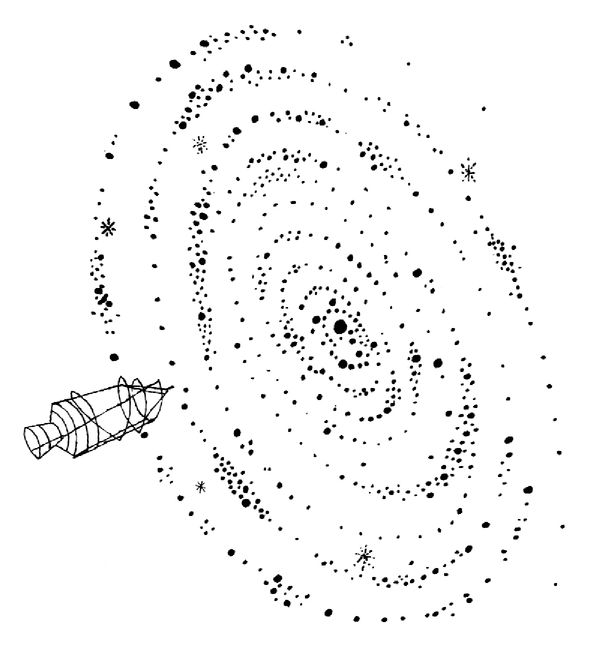

Since most of us had to stay strapped down, we couldn't look at the view, and there were no viewports anyway. There was, however, a wide screen closed-circuit TV setup over our heads, on which they showed Earth. It was beautiful, but it was hard to take in the fact that it wasn't just a video, like so many I'd seen before. For this reason it didn't make a very deep impression on me until later when I saw the real thing from the

Susie.

Then, too, my mind was well occupied with the mere thought of being in space, plus the nagging question,

What was I assuming that he could have resented?

Susie.

Then, too, my mind was well occupied with the mere thought of being in space, plus the nagging question,

What was I assuming that he could have resented?

Dad was deep in a discussion with the man on his left, who was a nonresident engineer returning to Mars from his biennial vacation. They'd found they had a lot to talk about, most of it hopelessly technical. So after we finished eating I was thrown back on Alex, although really I wished that I didn't have to be. I thought of pretending to be asleep, but I suspected that already he knew me too well to think I'd sleep under such conditions. He'd respect my privacy if I tried it, but his feelings might be hurt, and I didn't want that.

As it turned out, though, I had nothing to worry about. Our conversation was simply friendly, and I didn't once get the vague sense of inadequacyâthat uncomfortable, unsure feelingâthat Alex's response to my assumptions had brought on before.

Â

Â

Alex told me that he had come to Earth for a year of graduate work, and that he had just received his master's degree in business administration from the University of California. The Colonies, I learned, had a greater shortage of administrators than of scientists. He talked quite a bit about Mars, and it wasn't until afterward that I recognized any pattern in the way he described it.

Other books

Eleven Weeks by Lauren K. McKellar

Stepbrother With Benefits by Lana J. Swift

Emmy & Oliver by Benway,Robin

Berried to the Hilt by Karen MacInerney

Dead Deceiver by Victoria Houston

SHAFTED: an erotic thriller by Hayden, Rachael

Chosen by Lisa Mears

Rogue Stallion (Chrome Horsemen MC Book 2) by Carmen Faye

Return to Me by Morgan O'Neill

Her Forbidden Affair by Bexley, Rayne