Josie Under Fire (9 page)

Authors: Ann Turnbull

Josie looked startled at that.

“We are fighting this war,” Miss Rutherford said, “so that decency and goodness prevail. To ensure that no one’s rights are taken away; no one is oppressed; no one is bullied or hurt. So even if someone is our enemy we must treat them as we would wish to be treated ourselves.”

Josie nodded. “But Edith—”

“Oh! Edith!” Miss Rutherford exclaimed. “Why do you care so much what Edith thinks?”

“I’m scared of what she might say,” Josie admitted.

She began to explain about Ted, the tribunal, the war work.

As she had hoped, Miss Rutherford did not look shocked.

“I don’t have any friends in Greenwich,” Josie continued. “My best friend, Kathleen, was evacuated, and everyone else turned against me. I got bullied every day: just words, but horrible words… You can’t imagine…”

“Oh, I think I can,” said Miss Rutherford. “So when you were sent here it was a fresh start? New people who didn’t know?”

“Yes. Only now…Ted’s got leave and he’s coming to see me. And I want to see him. I really do. But if the others found out – the girls, or Vic…”

Miss Rutherford got up. “Let me show you some photographs.”

Josie brightened at once. She liked photographs.

Miss Rutherford opened a cabinet and brought out a leather-bound album. She sat beside Josie on the chaise longue and opened it across both their laps.

Josie was startled to see, not family photographs as she’d expected, but pictures of political demonstrations: large groups of women in old-fashioned long dresses and hats, marching, and holding up placards. “VOTES FOR WOMEN!” the placards demanded. “SUFFRAGE FOR ALL”. There were policemen, women chained to railings, women in Trafalgar Square speaking to huge crowds…

“The suffragettes!” she said. “Is that Mrs. Pankhurst?”

“Yes. And that’s Sylvia, her daughter; and Christabel… But here, do you see these two young women holding a banner between them?”

“That’s you!” exclaimed Josie.

“Yes. And the other one is my friend Violet Cross, who also used to live here. For a year or so, before the last war, we both dedicated our lives to the cause.”

Josie began to understand. “Did your friends turn against you?”

“Many of them – yes. And my father was – oh, so upset! And Mother’s friends were shocked. It was very distressing. I made my family suffer.”

“But you had to.”

“Yes. It was the right thing to do. I still believe that. And Ted – you mustn’t be ashamed of him. He’s doing the right thing too.”

“But – you served in the last war. You were a nurse, weren’t you? And now you’re an air-raid warden. Are

you

a pacifist?”

“I didn’t say I agreed with your brother. I said he was right to do what he believed in – not simply to go along with the crowd.”

“You’re saying I should stick up for Alice Hampton.”

“I think

you

are saying that.”

Josie looked down at the photographs. The suffragettes didn’t go along with the crowd. And yet there, on the march, they

were

a crowd.

It’s different for me, she thought. I’m on my own.

But she knew she had to make a stand.

Chapter Twelve

Four Eyes

“What were you doing up there?” demanded Edith. She never liked to feel she was missing out on anything.

“Talking. And looking at photographs.”

“Photographs!”

“Miss Rutherford used to be a suffragette.”

Edith’s eyes widened. “I never knew that! Was she in prison? Did she go on hunger strike? Or chain herself to railings?”

“I don’t know.”

“You didn’t find out much, then.”

Josie tried to explain. “I told her about the attack on Hampton’s – what I’d said to Vic. We were talking about defending people, and standing up for what you believe in. I told her about Ted as well.”

“He’ll be here soon, won’t he?”

“Wednesday.”

Edith smiled. “That’ll be fun. Perhaps we’ll go out somewhere. And Mummy’s sure to do something nice for dinner.”

“Ted’s not fussy,” said Josie. She remembered him, fondly, reading at the dinner table (much to their mother’s annoyance), talking politics, hardly aware of what he was eating.

She was conscious that they had strayed from the subject of her talk with Miss Rutherford. She tried again: “Edith, we’ve got to stop picking on Alice Hampton. It’s gone too far.”

Edith looked defensive. “

We

didn’t throw that brick! It’s nothing to do with us.”

“All the same – we should leave her alone now.”

Edith shrugged. “She’s boring, anyway.”

Perhaps the others

will

have grown bored with the game, Josie thought. Perhaps I won’t need to stand up for her.

The next day, Easter Monday, the snow finally came: only a brief flurry, but for a while the sky was full and the pavements sparkled under a fine, fast-melting layer.

“In the middle of April!” Aunty Grace exclaimed.

The girls were delighted. They went out into Chelsea Walk and tried sliding on the pavement, but the snow was too wet. They crossed over to the Embankment and saw both sky and water blotted out, the buildings of Battersea hidden and the barrage balloons like strange monsters emerging from mist.

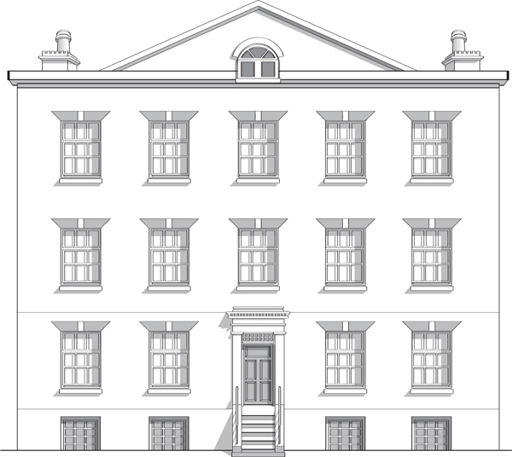

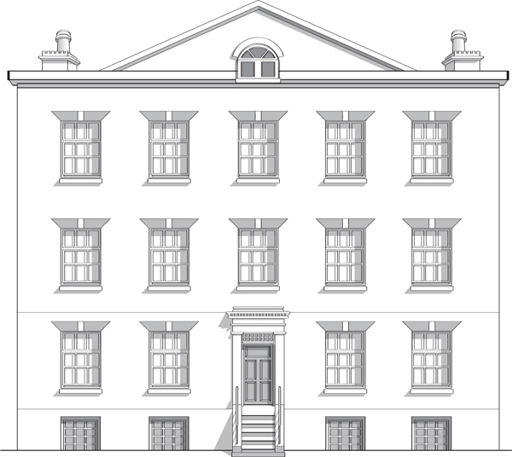

Josie looked back through the trees at the house and thought how beautiful the scene looked in the softly falling snow. This could be any time, she thought: now, or the future, or a hundred years ago. The house would always be the same.

But by the afternoon the snow had melted.

Tuesday was cold and dull. Edith and Josie put their knitting into bags and set off for school. They did not have to wear uniform today. The knitting session was to take place in the hall, and chairs had been placed randomly. Josie had convinced herself that Alice Hampton would not come, but she was disappointed. As the girls began arriving she saw that Alice was there, and so were Clare, Pam and Sylvia.

Edith went straight to her friends. “Did you hear about Hampton’s shop?” They whispered and glanced at Alice, who noticed, and ignored them.

Josie kept away from their talk. She was besieged by guilt.

Miss Hallam called them all to attention, and told them they would spend most of the morning knitting, and then the work would be collected up, stars awarded and photographs taken.

“Anything you haven’t finished can wait till after the holiday,” she said. “And since this is not a school day you may sit where you like, and talk if you wish. And we shall also have some singing.”

Clare, Pam and Edith began grabbing chairs. They set five of them in a semi-circle, and Josie and Sylvia joined them. Josie saw Alice casting about, uncertain where to sit, unwilling to ask to join a group. She

is

shy, Josie thought; she doesn’t know how to make friends. In the end Alice sat on one of the few chairs left, on the fringes of another group, trying to look as if she was part of it.

They all got out their work, and Mrs. Burton from the WVS started them off singing. They sang

Pack up your Troubles

;

Run, Rabbit, Run

;

The White Cliffs of Dover

; and

Jerusalem

. Someone suggested

Whistle While you Work

, and they all sang with loud enthusiasm:

“Whistle while you work

Hitler is a twerp

Goering’s barmy

So’s his army

Whistle while you work…”

When the time was up Josie had finished her balaclava. Edith’s scarf came to a natural end and she cast off. Amid much laughter they each put on their own garments (socks went on hands) and Miss Hallam encouraged them to stand close together while a man from the local paper took several photographs. There was a list of names on the wall and everyone who had finished a garment was awarded a star.

At last all the items were put into boxes to be sorted and sent on by the WVS.

The girls began leaving for home. Josie saw Alice going out of the door and willed her to be quickly on her way.

Edith was in a huddle with Pam and Clare.

“We’re going to the bomb site,” she told Josie a few minutes later.

“The one we went to before?” Josie was alarmed.

“Yes.”

“But – we’ve been warned…”

“The teachers won’t know. It’s the holidays. No one can write or complain until we go back, and that’s ages.”

“I don’t think—”

“Oh, come on, Josie. My friends want to go. It’ll be something to do.”

Josie knew they were hoping the boys would be there. She half hoped that, too; but also half feared it, because of what had happened at Hampton’s. But at least, she thought, if we go to the bomb site we won’t be pursuing Alice on her way home.

The boys were not there. Some younger children were playing in the ruins, but there was no sign of Vic and his friends. The girls played tag, clambering over the rubble, hiding, shrieking when they were caught. But it was not the same without the boys. If the boys had appeared the shrieks would have been designed to attract their attention; the game would gradually have moved closer to them; and in the end it would have been abandoned in favour of chatting, giggling and showing off. There would have been a sparkle in the air.

But this was just a girls’ game that soon became boring. Josie, with her eyes shut, counted to a hundred, opened them, and saw – walking along the road, head down, satchel across her shoulders – Alice Hampton.

She knew what would happen now – and felt a surge of irritation against Alice. Why couldn’t the girl have found another way to Belmont Gardens? Perhaps she’d thought her enemies wouldn’t dare go to the bomb site again. Well, they’d catch her now.

Pam came out of hiding. “Hey! There’s Hauptmann!”

The others emerged.

“She’s going to her coaching.”

“Doesn’t she know it’s the holidays?”

“Ve never stop vork. Even in ze holidays.”

They began moving towards the girl.

“Oh, leave her alone!”

Josie tried to sound commanding, but she knew it was hopeless. Suddenly the bomb site had ceased to be boring. If they’d had the company of the boys, the girls might not have bothered with Alice; but now Alice would provide the missing excitement.

“Let’s get her.”

They began to run. Josie shouted, “I’m not coming! Edith, I’m not coming with you!”

But Edith followed her friends.

Josie watched them reach Alice and circle round her. She heard their taunts – “Hauptmann!” “Nazi!” – and saw Alice struggling to push past them. Edith gave a Nazi salute. They sang:

“

Vhistle vhile you vork

Hauptmann is a tverp…

”

Pam seized Alice’s bag and tipped its contents on the ground.

It was then that Josie knew she had to do more than stand aside. She ran across the bomb site to where the others had now begun to kick Alice’s books around.

“Stop it!” she shouted – with such passion that they were startled and stared at her. “Her family aren’t Nazis! You know that. And even if they were” – she began picking up Alice’s books and brushing the dirt off them – “it’s just stupid! Stupid!”

“Oh, run home to Mummy, Four Eyes!” said Pam. “We don’t need you.”

Josie had often been called that name before. It always hurt.

“Four Eyes!” echoed Sylvia, giggling.

Josie didn’t look at Edith; she was too angry with her. Alice had her books now and was fastening her satchel as she moved away. Josie walked beside her.

“I’ll go with you,” she said to Alice. “I won’t let them hurt you.”

“I’m all right,” muttered Alice. She quickened her pace, making Josie run to keep up.

Josie, determined to make amends, scurried beside her.

“I’m all

right

!” Alice snapped. “Leave me alone.”

She began to run. And then, suddenly, she stopped and turned round, her eyes wide and pleading. “It wasn’t true, was it?” she said. “You made that up about my grandfather? About him changing his name? Didn’t you?”

And Josie realized that Alice hadn’t known.

Chapter Thirteen