Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (99 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

"I see," said Stephen. "But, though the magician is ignorant, he has still succeeded. After all, you are here, sir, are you not?"

"Yes, I dare say," said the gentleman in an irritated tone. "But that does not detract from the fact that the magic that brought me here is clumsy and inelegant! Besides what does it profit him? Nothing! I do not chuse to shew myself to him and he knows no magic to counteract that. Stephen! Quick! Turn the pages of that book! There is no breeze in the room and it will perplex him beyond any thing. Ha! See how he stares! He half-suspects that we are here, but he cannot see us. Ha, ha! How angry he is becoming! Give his neck a sharp pinch! He will think it is a mosquito!"

1

The Tree of Learning

by Gregory Absalom (1507–99)

2 A famous cafe on the San Marco Piazza.

3 Aunt Greysteel is probably speaking of the Derwent. Long ago, when John Uskglass was still a captive child in Faerie, a king in Faerie foretold that if he came to adulthood, then all the old fairy kingdoms would fall. The king sent his servants into England to bring back an iron knife to kill him. The knife was forged by a blacksmith on the banks of the Derwent and the waters of the Derwent were used to cool the hot metal. However, the attempt to kill John Uskglass failed and the king and his clan were destroyed by the boy-magician. When John Uskglass entered England and established his kingdom, his fairy- followers went in search of the blacksmith. They killed him and his family, destroyed his house and laid magic spells upon the Derwent to punish it for its part in making the wicked knife.

4 The views Strange is expressing at this point are wildly optimistic and romantic. English magical literature is full of examples of fairies whose powers were weak or who were stupid or ignorant.

5 Jacques Belasis was reputed to have created an excellent spell for summon- ing fairy-spirits. Unfortunately the only copy of Belasis's masterpiece,

The

nstructions

, was at the library at Hurtfew and Strange had never seen it. All he knew of it were vague descriptions in later histories and so it must be assumed that Strange was re-creating this magic and had only the flimsiest notion of what he was aiming at.

By contrast, the spell commonly attributed to the Master of Doncaster is very well known and appears in a number of widely available works. The identity of the Master of Doncaster is not known. His existence is deduced from a handful of references in

Argentine

histories to thirteenth-century magicians acquiring spells and magic "from Doncaster". Moreover, it is far from clear that all the magic attributed to the Master of Doncaster is the work of one man. This has led magio-historians to postulate a second magician, even more shadowy than the first, the Pseudo-Master of Doncaster. If, as has been convincingly argued, the Master of Doncaster was really John Uskglass, then it is logical to assume that the spell of summoning was created by the Pseudo-Master. It seems highly unlikely that John Uskglass would have had any need of a spell to summon fairies. His court was, after all, full of them.

End of November 1816

S

OME TIME BEFORE he had left England Dr Greysteel had received a letter from a friend in Scotland, begging that, if he were to get as far as Venice, he would pay a visit to a certain old lady who lived there. It would be, said the Scottish friend, an act of charity, since this old lady, once rich, was now poor. Dr Greysteel thought he remembered hearing once that she was of some odd, mixed parentage – as it might be half-Scottish, half-Spanish or perhaps half-Irish, half-Hebrew.

Dr Greysteel had always intended to visit her, but what with inns and carriages, sudden removals and changes of plan, he had discovered, on arriving at Venice, that he could no longer lay his hand on the letter and no longer retained a very clear impression of its contents. Nor had he any note of her name – nothing but a little scrap of paper with the direction where she might be found.

Aunt Greysteel said that under such very difficult circumstances as these, they would do best to send the old lady a letter informing her of their intention to call upon her. Though, to be sure, she added, it would look very odd that they did not know her name – doubtless she would think them a sad, negligent sort of people. Dr Greysteel looked uncomfortable, and sniffed and fidgeted a good deal, but he could think of no better plan and so they wrote the note forthwith and gave it to their landlady, so that she might deliver it to the old lady straightaway.

Then came the first odd part of the business, for the landlady studied the direction, frowned and then – for reasons which Dr Greysteel did not entirely comprehend – sent it to her brother-in-law on the island of Giudecca.

Some days later this same brother-in-law – an elegant little Venetian lawyer – waited upon Dr Greysteel. He informed Dr Greysteel that he had sent the note, just as Dr Greysteel had requested, but Dr Greysteel should know that the lady lived in that part of the city which was called Cannaregio, in the Ghetto – where the Jews lived. The letter had been delivered into the hands of a venerable Hebrew gentleman. There had been no reply. How did Dr Greysteel wish to proceed? The little Venetian lawyer was happy to serve Dr Greysteel in any way he could.

In the late afternoon Miss Greysteel, Aunt Greysteel, Dr Grey- steel and the lawyer (whose name was Signor Tosetti), glided through the city in a gondola – through that part of the city which is called St Mark's where they saw men and women preparing for the night's pleasures – past the landing of Santa Maria Zobenigo, where Miss Greysteel turned back to gaze at a little candlelit window, which might have belonged to Jonathan Strange – past the Rialto where Aunt Greysteel began to tut and sigh and wish very much that she saw more shoes upon the children's feet.

They left the gondola at the Ghetto Nuovo. Though all the houses of Venice are strange and old, those of the Ghetto seemed particu- larly so – as if queerness and ancientness were two of the commod- ities this mercantile people dealt in and they had constructed their houses out of them. Though all the streets of Venice are melancholy, these streets had a melancholy that was quite distinct – as if Jewish sadness and Gentile sadness were made up according to different recipes. Yet the houses were very plain and the door upon which Signor Tosetti knocked was black enough and humble enough to have done for any Quaker meeting-house in England.

The door was opened by a manservant who let them into the house and into a dark chamber panelled with dried-out, ancient- looking wood that smelt of nothing so much as the sea.

There was a door in this chamber that was open a little. From where he stood Dr Greysteel could see ancient, battered-looking books in thin leather bindings, silver candlesticks that had sprouted more branches than English candlesticks generally do, mysterious-looking boxes of polished wood – all of which Dr Greysteel took to be connected with the Hebrew gentleman's religion. Hung upon the wall was a doll or puppet as tall and broad as a man, with huge hands and feet, but dressed like a woman, with its head sunk upon its breast so that its face could not be seen.

The manservant went through this door to speak to his master. Dr Greysteel whispered to his sister that the servant was decent- looking enough. Yes, said Aunt Greysteel, except that he wore no coat. Aunt Greysteel said that she had often noticed that male servants were always liable to present themselves in their shirt- sleeves and that it was often the case that if their masters were single gentlemen then nothing would be done to correct this bad habit. Aunt Greysteel did not know why this should be. Aunt Greysteel supposed that the Hebrew gentleman was a widower.

"Oh!" said Dr Greysteel, peeping through the half-open door- way. "We have interrupted him at his dinner."

The venerable Hebrew gentleman wore a long, dusty black coat and had a great beard of curly grey and white hairs and a black skullcap on top of his head. He was seated at a long table upon which was laid a spotless white linen cloth and he had tucked a generous portion of this into the neck of his black robe to serve him as a napkin.

Aunt Greysteel was very shocked that Dr Greysteel should be spying through chinks in doorways and attempted to make him stop by poking at him with her umbrella. But Dr Greysteel had come to Italy to see everything he could and saw no reason to make an exception of Hebrew gentlemen in their private apart- ments.

This particular Hebrew gentleman did not seem inclined to interrupt his dinner to wait upon an unknown English family; he appeared to be instructing the manservant in what to say to them.

The servant came back and spoke to Signor Tosetti and when he had finished Signor Tosetti bowed low to Aunt Greysteel and explained that the name of the lady they sought was Delgado and that she lived at the very top of the house. Signor Tosetti was a little annoyed that none of the Hebrew gentleman's servants seemed willing to shew them the way and announce their arrival, but, as he said, their party was one of bold adventurers and doubtless they could find their way to the top of a staircase.

Dr Greysteel and Signor Tosetti took a candle each. The staircase wound up into the shadows. They passed many doors which, although rather grand, had a queer, stunted look about them – for in order to accommodate all the people, the houses in the Ghetto had been built as tall and with as many storeys as the householders had dared – and to compensate for this all the ceilings were rather low. At first they heard people talking behind these doors and at one they heard a man singing a sad song in an unknown language. Then they came to doors that stood open shewing only darkness; a cold, stale draught came from each. The last door, however, was closed. They knocked, but no one an- swered. They called out they were come to wait upon Mrs Delgado. Still no reply. And then, because Aunt Greysteel said that it was foolish to come so far and just go away again, they pushed open the door and went inside.

The room – which was scarcely more than an attic – had all the wretchedness that old age and extreme poverty could give it. It contained nothing that was not broken, chipped or ragged. Every colour in the room had faded, or darkened, or done what it must until it was grey. There was one little window that was open to the evening air and shewed the moon, although it was a little surpriz- ing that the moon with her clean white face and fingers should condescend to make an appearance in that dirty little room.

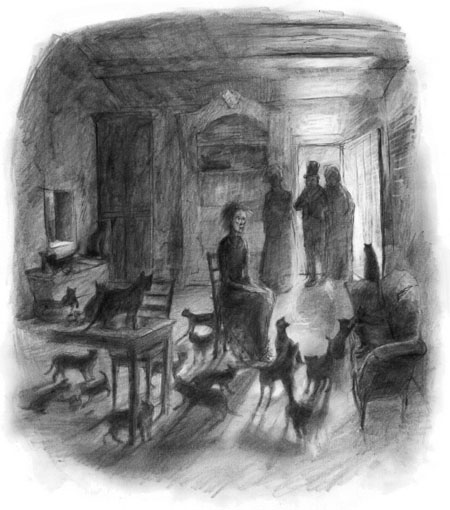

Yet this was not what made Dr Greysteel look so alarmed, made him pull at his neckcloth, redden and go pale alternately, and draw great breaths of air. If there was one thing which Dr Greysteel disliked more than another, it was cats – and the room was full of cats.

In the midst of the cats sat a very thin person on a dusty, wooden chair. It was lucky, as Signor Tosetti had said, that the Greysteels were all bold adventurers, for the sight of Mrs Delgado might well have been a little shocking to nervous persons. For though she sat very upright – one would almost have said that she was poised, waiting for something – she bore so many of the signs and disfigurings of extreme old age that she was losing her resemblance to other human beings and began instead to resemble other orders of living creatures. Her arms lay in her lap, so extravagantly spotted with brown that they were like two fish. Her skin was the white, almost transparent skin of the extremely old, as fine and wrinkled as a spider's web, with veins of knotted blue.

She did not rise at their entrance, nor make any sign that she had noticed them at all. But perhaps she did not hear them. For, though the room was silent, the silence of half a hundred cats is a peculiar thing, like fifty individual silences all piled one on top of another.

So the Greysteels and Signor Tosetti, practical people, sat down in the terrible little room and Aunt Greysteel, with her kind smile and solicitous wishes that every one should be made comfortable and easy, began their addresses to the old lady.

"I hope, my dear Mrs Delgado, that you will forgive this intrusion, but my niece and I wished to do ourselves the honour of waiting upon you." Aunt Greysteel paused in case the old lady wished to make a reply, but the old lady said nothing. "What an airy situation you have here, ma'am! A dear friend of mine – a Miss Whilesmith – lodges in a little room at the top of a house in

Queen's square in Bath – a room much like your own, Mrs Delgado – and she declares that in summer she would not exchange it for the best house in the city – for she catches the breezes that nobody else gets and is perfectly cool when great people stifle in their rich apartments. And she has everything so neat and tidy and just to hand, whenever she wants it. And her only complaint is that the girl from the second back pair is always putting hot kettles on the staircase – which, as you know Mrs Delgado – can be so very displeasing if you chance to strike your foot against one of them. Do you suffer much inconvenience from the staircase, ma'am?"