Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (60 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

"Is it though?" said Strange, greatly interested. "I have seen statues of him of course. And engravings in books. But I do not think I ever saw a painting before. And the lady between the two kings, who is she?"

"That is Mrs Gwynn, one of the mistresses of Charles II. She is meant to represent Britannia."

"I see. It is something, I suppose, that he still has a place of honour in the King's house. But then they put him in Roman dress and make him hold hands with an actress. I wonder what he would say to that?"

The servant led Strange back through the weapon-lined room to a black door of imposing size overtopped with a great jutting marble pediment.

"I can take you no further than this, sir. My business ends here and the Dr Willises' begins. You will find the King behind that door." He bowed and went back down the stairs.

Strange knocked on the door. From somewhere inside came the sound of a harpsichord and someone singing.

The door opened to reveal a tall, broad fellow of thirty or forty. His face was round, white, pockmarked and be dabbled with sweat like a Cheshire cheese. All in all he bore a striking resemblance to the man in the moon who is reputed to be made of cheese. He had shaved himself with no very high degree of skill and here and there on his white face two or three coarse black hairs appeared — rather as if a family of flies had drowned in the milk before the cheese was made and their legs were poking out of it. His coat was of rough brown drugget and his shirt and neckcloth were of the coarsest linen. None of his clothes were particularly clean.

"Yes?" he said, keeping his hand upon the door as if he intended to shut it again at the least provocation. He had very little of the character of a palace servant and a great deal of the character of a madhouse attendant, which was what he was.

Strange raised his eyebrow at this rude behaviour. He gave his name rather coldly and said he had come to see the King.

The man sighed. "Well, sir, I cannot deny that we were expecting you. But, you see, you cannot come in. Dr John and Dr Robert . . ." (These were the names of the two Willis brothers) ". . . are not here. We have been expecting them every minute for the past hour and a half. We do not understand where they can have got to."

"That is most unfortunate," said Strange. "But it is none of my concern. I have no desire to see the gentlemen you mention. My business is with the King. I have a letter signed by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York granting me permission to visit His Majesty today." Strange waved the letter in the man's face.

"But you must wait, sir, until Dr John and Dr Robert come. They will not allow any one to interfere with their system of managing the King. Silence and seclusion are what suits the King best. Conversation is the very worst thing for him. You can scarcely imagine, sir, what terrible harm you might do to the King merely by speaking to him. Say you were to mention that it is raining. I dare say you would consider that the most innocent remark in the world. But it might set the King a-thinking, you see, and in his madness his mind runs on from one thing to another, enraging him to a most dangerous degree. He might think of times in the past when it rained and his servants brought him news of battles that were lost, and daughters that were dead, and sons that had disgraced him. Why! It might be enough to kill the King outright! Do you want to kill the King, sir?"

"No," said Strange.

"Well, then," said the man coaxingly, "do you not see, sir, that it would be far better to wait for Dr John and Dr Robert?"

"Thank you, but I think I will take my chances. Conduct me to the King if you please."

"Dr John and Dr Robert will be very angry," warned the man.

"I do not care if they are," replied Strange coolly.

The man looked entirely astonished at this.

"Now," said Strange, with a most determined look and another flourish of his letter, "will you let me see the King or will you defy the authority of two Archbishops? That is a very grave matter, punishable by . . . well, I do not exactly know what, but some-thing rather severe, I should imagine."

The man sighed. He called to another man (as rough and dirty as himself) and told him to go immediately to the houses of Dr John and Dr Robert to fetch them. Then with great reluctance he stood aside for Strange to enter.

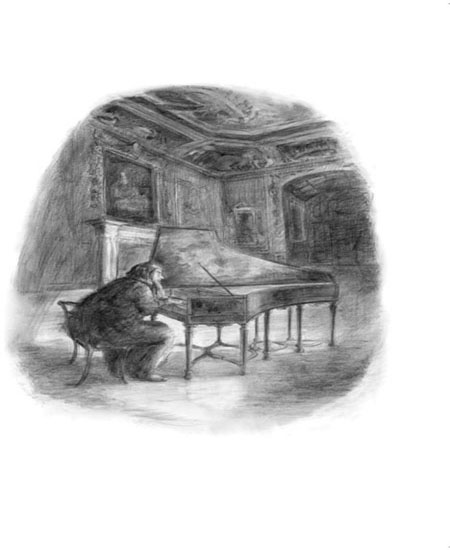

The proportions of the room were lofty. The walls were panelled in oak and there was a great deal of fine carving. More royal and symbolic personages lounged about upon clouds on the ceiling. But it was a dreary place. There was no covering upon the floor and it was very cold. A chair and a battered-looking harpsichord were the only furniture. An old man was seated at the harpsichord with his back to them. He was dressed in a dressing-gown of ancient purple brocade. There was a crumpled nightcap of scarlet velvet on his head and dirty broken slippers on his feet. He was playing with great vigour and singing loudly in German. When he heard the sound of approaching footsteps he stopped.

"Who's there?" he demanded. "Who is it?"

"The magician, Your Majesty," said the madhouse attendant.

The old man seemed to consider this a moment and then he said in a loud voice, "It is a profession to which I have a particular dislike!" He struck the keys of his harpsichord again and resumed his loud singing.

This was rather a discouraging beginning. The madhouse attendant gave an impertinent snigger and walked off, leaving Strange and the King alone. Strange took a few paces further into the room and placed himself where he might observe the King's face.

It was a face in which all the misery of madness was compounded by the misery of blindness. The eyes had irises of clouded blue and whites as discoloured as rotten milk. Long locks of whitish hair streaked with grey hung down on either side of cheeks patched with broken veins. As the King sang, spittle flew from his slack red lips. His beard was almost as long and white as his hair. He was nothing at all like the pictures Strange had seen of him, for they had been made when he was in his right mind. With his long hair, long beard and long, purple robe, what he chiefly resembled was someone very tragic and ancient out of Shakespeare — or, rather, two very tragic and ancient persons out of Shake-speare. In his madness and his blindness he was Lear and Glou-cester combined.

Strange had been cautioned by the Royal Dukes that it was contrary to Court etiquette to speak to the King unless the King addressed him first. However there seemed little hope of this since the King disliked magicians so much. So when the King ceased his playing and singing again, he said, "I am Your Majesty's humble servant, Jonathan Strange of Ashfair in Shropshire. I was Magician-in-Ordinary to the Army during the late war in Spain where, I am happy to say, I was able to do Your Majesty some service. It is the hope of Your Majesty's sons and daughters that my magic might afford Your Majesty some relief from your illness."

"Tell the magician I do not see him!" said the King airily.

Strange did not trouble to make any reply to this nonsensical remark. Of course the King could not see him, the King was blind.

"But I see his companion

very

well

!" continued His Majesty in an approving tone. He turned his head as though to gaze at a point two or three feet to the left of Strange. "With such silver hair as he has got, I think I ought to be able to see him! He looks a very wild fellow."

So convincing was this speech that Strange actually turned to look. Of course there was no one.

In the past few days he had searched Norrell's books for something pertinent to the King's condition. There were remarkably few spells for curing madness. Indeed he had found only one, and even then he was not sure that was what it was meant for. It was a prescription in Ormskirk's

Revelations

of

Thirty-Six

Other

Worlds

. Ormskirk said that it would dispel illusions and correct wrong ideas. Strange took out the book and read through the spell again. It was a peculiarly obscure piece of magic, consisting only of the following words:

Place

the

moon

at

his

eyes

and

her

whiteness

shall

devour

the

false

sights

the

deceiver

has

placed

there.

Place

a

swarm

of

bees

at

his

ears.

Bees

love

truth

and

will

destroy

the

deceiver's

lies.

Place

salt

in

his

mouth

lest

the

deceiver

attempt

to

delight

him

with

the

taste

of

honey

or

disgust

him

with

the

taste

of

ashes.

Nail

his

hand

with

an

iron

nail

so

that

he

shall

not

raise

it

to

do

the

deceiver's

bidding.

Place

his

heart

in

a

secret

place

so

that

all

his

desires

shall

be

his

own

and

the

deceiver

shall

find

no

hold

there.

Memorandum.

The

colour

red

may

be

found

beneficial.

However, as Strange read it through, he was forced to admit that he had not the least idea what it meant.

2

How was the magician supposed to fetch the moon to the afflicted person? And if the second part were correct, then the Dukes would have done better to employ a beekeeper instead of a magician. Nor could Strange believe that their Royal Highnesses would be best pleased if he began piercing the King's hands with iron nails. The note about the colour red was odd too. He thought he remembered hearing or reading something about red but he could not at present recall what it was.

The King, meanwhile, had fallen into conversation with the imaginary silver-haired person. "I beg your pardon for mistaking you for a common person," he said. "You may be a king just as you say, but I merely take the liberty of observing that I have never heard of any of your kingdoms. Where is Lost-hope? Where are the Blue Castles? Where is the City of Iron Angels? I, on the other hand, am King of

Great

Britain

, a place everyone knows and which is clearly marked on all the maps!" His Majesty paused, presumably to attend to the silver-haired person's reply for he suddenly cried out, "Oh, do not be angry! Pray, do not be angry! You are a king and I am a king! We shall all be kings together! And there is really no need for either of us to be angry! I shall play and sing for you!" He drew a flute from the pocket of his dressing-gown and began to play a melancholy air.

As an experiment Strange reached forward and plucked off His Majesty's scarlet nightcap. He watched closely to see if the King grew any more mad without it, but after several minutes of observation he was forced to admit that he could see no difference. He put the nightcap back on.

For the next hour and a half he tried all the magic he could think of. He cast spells of remembering, spells of finding, spells of awakening, spells to concentrate the mind, spells to dispel night-mares and evil thoughts, spells to find patterns in chaos, spells to find a path when one was lost, spells of demystification, spells of discernment, spells to increase intelligence, spells to cure sickness and spells to repair a limb that is shattered. Some of the spells were long and complicated. Some were a single word. Some had to be said out loud. Some had only to be thought. Some had no words at all but consisted of a single gesture. Some were spells that Strange and Norrell had employed in some form or other every day for the last five years. Some had probably not been used for centuries. Some used a mirror; two used a tiny bead of blood from the magician's finger; and one used a candle and a piece of ribbon. But they all had this in common: they had no effect upon the King whatsoever.