Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (13 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

Sir Walter had a generous spirit and was often kind-hearted. He told someone once that he hoped his enemies all had reason to fear him and his friends reason to love him — and I think that upon the whole they did. His cheerful manner, his kindness and cleverness, the great station he now held in the world — these were even more to his credit as he maintained them in the face of problems that would almost certainly have brought down a lesser man. Sir Walter was distressed for money. I do not mean that he merely lacked for cash. Poverty is one thing, Sir Walter's debts quite another. Miserable situation! — and all the more bitter since it was no fault of his:

he

had never been extravagant and he had certainly never been foolish, but he was the son of one imprudent man and the grandson of another. Sir Walter had been born in debt. Had he been a different sort of man, then all might have been well. Had he been at all inclined to the Navy then he might have made his fortune in prize money; had he loved farming he might have improved his lands and made his money with corn. Had he even been a Minister fifty years before he might have lent out Treasury- money at twenty per cent interest and pocketed the profit. But what can a modern politician do? — he is more likely to spend money than make it.

Some years ago his friends in Government had got him the position of Secretary-in-Ordinary to the Office of Supplication, for which he received a special hat, a small piece of ivory and seven hundred pounds a year. There were no duties attached to the place because no one could remember what the Office of Supplication was supposed to do or what the small piece of ivory was for. But then Sir Walter's friends went out and new Ministers came in, declaring that they were going to abolish sinecures, and among the many offices and places which they pruned from the tree of Government was the Office of Supplication.

By the spring of 1807 it seemed as if Sir Walter's political career must be pretty much at an end (the last election had cost him almost two thousand pounds). His friends were almost frantic. One of those friends, Lady Winsell, went to Bath where, at a concert of Italian music, she made the acquaintance of some people called Wintertowne, a widow and her daughter. A week later Lady Winsell wrote to Sir Walter: "It is exactly what I have always wished for you. Her mother is all for a great marriage and will make no difficulties — or at least if she does then I rely upon

you

to charm them away. As for the money! I tell you, my dear friend, when they named the sum that is to be hers, tears sprang into my eyes! What would you say to one thousand a year? I will say nothing of the young person herself — when you have seen her you shall praise her to me much more ably than ever I could to you." At about three o'clock upon the same day that Mr Drawlight attended the recital by the Italian lady, Lucas, Mr Norrell's footman, knocked upon the door of a house in Brunswick-square where Mr Norrell had been summoned to meet Sir Walter. Mr Norrell was admitted to the house and was shown to a very fine room upon the first floor.

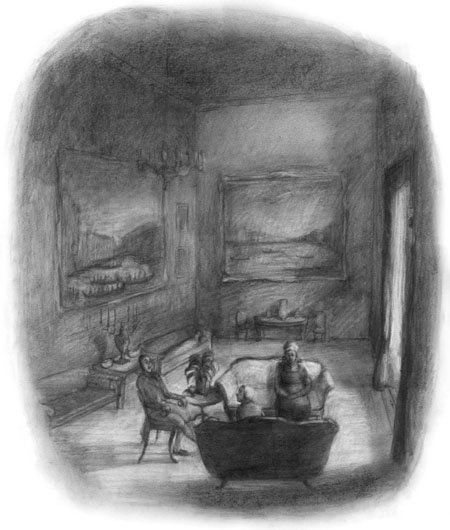

The walls were hung with a series of gigantic paintings in gilded frames of great complexity, all depicting the city of Venice, but the day was overcast, a cold stormy rain had set in, and Venice — that city built of equal parts of sunlit marble and sunlit sea — was drowned in a London gloom. Its aquamarine-blues and cloud- whites and glints of gold were dulled to the greys and greens of drowned things. From time to time the wind flung a little sharp rain against the window (a melancholy sound) and in the grey light the well-polished surfaces of tulipwood

chiffoniers

and walnut writing-tables had all become black mirrors, darkly reflecting one another. For all its splendour, the room was peculiarly comfortless; there were no candles to light the gloom and no fire to take off the chill. It was as if the housekeeping was under the direction of someone with excellent eyesight who never felt the cold.

Sir Walter Pole rose to receive Mr Norrell and begged the honour of presenting Mrs Wintertowne and her daughter, Miss Wintertowne. Though Sir Walter spoke of

two

ladies, Mr Norrell could perceive only

one

, a lady of mature years, great dignity and magisterial aspect. This puzzled Mr Norrell. He thought Sir Walter must be mistaken, and yet it would be rude to contradict Sir Walter so early in the interview. In a state of some confusion, Mr Norrell bowed to the magisterial lady.

"I am very glad to meet you, sir," said Sir Walter. "I have heard a great deal about you. It seems to me that London talks of very little else but the extraordinary Mr Norrell," and, turning to the magisterial lady, Sir Walter said, "Mr Norrell is a magician, ma'am, a person of great reputation in his native county of Yorkshire."

The magisterial lady stared at Mr Norrell.

"You are not at all what I expected, Mr Norrell," remarked Sir Walter. "I had been told you were a

practical

magician — I hope you are not offended, sir — it is merely what I was told, and I must say that it is a relief to me to see that you are nothing of the sort. London is plagued with a great number of mock-sorcerers who trick the people out of their money by promising them all sorts of unlikely things. I wonder, have you seen Vinculus, who has a little booth outside St Christopher Le Stocks? He is the worst of them. You are a

theoretical

magician, I imagine?" Sir Walter smiled encouragingly. "But they tell me that you have something to ask me, sir."

Mr Norrell begged Sir Walter's pardon but said that he was indeed a practical magician; Sir Walter looked surprized. Mr Norrell hoped very earnestly that he would not by this admission lose Sir Walter's good opinion.

"No, no. By no means," murmured Sir Walter politely.

"The misapprehension under which you labour," said Mr Norrell, "by which I mean, of course, the belief that all practical magicians must be charlatans — arises from the shocking idleness of English magicians in the last two hundred years. I have performed one small feat of magic — which the people in York were kind enough to say they found astounding — and yet I tell you, Sir Walter, any magician of modest talent might have done as much. This general lethargy has deprived our great nation of its best support and left us defenceless. It is this deficiency which I hope to supply. Other magicians may be able to neglect their duty, but I cannot; I am come, Sir Walter, to offer you my help in our present difficulties."

"Our present difficulties?" said Sir Walter. "You mean the war?" He opened his small black eyes very wide. "My dear Mr Norrell! What has the war to do with magic? Or magic to do with the war? I believe I have heard what you did in York, and I hope the housewives were grateful, but I scarcely see how we can apply such magic to the war! True, the soldiers get very dirty, but then, you know," and he began to laugh, "they have other things of think of."

Poor Mr Norrell! He had not heard Drawlight's story of how the fairies had washed the people's clothes and it came as a great shock to him. He assured Sir Walter that he had never in his life washed linen — not by magic nor by any other means — and he told Sir Walter what he had really done. But, curiously, though Mr Norrell was able to work feats of the most breath-taking wonder, he was only able to describe them in his usual dry manner, so that Sir Walter was left with the impression that the spectacle of half a thousand stone figures in York Cathedral all speaking together had been rather a dull affair and that he had been fortunate in being elsewhere at the time. "Indeed?" he said. "Well, that is most interesting. But I still do not quite understand how . . ."

Just at that moment someone coughed, and the moment that Sir Walter heard the cough he stopped speaking as if to listen.

Mr Norrell looked round. In the furthest, most shadowy corner of the room a young woman in a white gown lay upon a sopha, with a white shawl wrapped tightly around her. She lay quite still. One hand pressed a handkerchief to her mouth. Her posture, her stillness, everything about her conveyed the strongest impression of pain and ill-health.

So certain had Mr Norrell been that the corner was unoccupied, that he was almost as startled by her sudden appearance as if she had come there by someone else's magic. As he watched she was seized by a fit of coughing that continued for some moments, and during that time Sir Walter appeared most uncomfortable. He did not look at the young woman (though he looked everywhere else in the room). He picked up a gilt ornament from a little table by his side, turned it over, looked at its underneath, put it down again. Finally he coughed — a brief clearing of the throat as though to suggest that everyone coughed — coughing was the most natural thing in the world — coughing could never, under any circumstances, be cause for alarm. The young woman upon the sopha came at last to the end of her own coughing fit, and lay quite still and quiet, though her breathing did not seem to come easily.

Mr Norrell's gaze travelled from the young lady to the great, gloomy painting that hung above her and he tried to recollect what he had been speaking of.

"It is a marriage," said the majestic lady.

"I beg your pardon, madam?" said Mr Norrell.

But the lady only nodded in the direction of the painting and bestowed a stately smile upon Mr Norrell.

The painting which hung above the young lady shewed, like every other picture in the room, Venice. English cities are, for the most part, built upon hills; their streets rise and fall, and it occurred to Mr Norrell that Venice, being built upon the sea, must be the flattest, as well as the queerest, city in the world. It was the flatness which made the painting look so much like an exercise in perspective; statues, columns, domes, palaces, and cathedrals stretched away to where they met a vast and melancholy sky, while the sea that lapped at the walls of those buildings was crowded with ornately carved and gilded barges, and those strange black Venetian vessels that so much resemble the slippers of ladies in mourning.

"It depicts the symbolic marriage of Venice to the Adriatic," said the lady (whom we must now presume to be Mrs Wintertowne), "a curious Italian ceremony. The paintings which you see in this room were all bought by the late Mr Wintertowne during his travels on the Continent; and when he and I were married they were his wedding-gift to me. The artist — an Italian — was then quite unknown in England. Later, emboldened by the patronage he received from Mr Wintertowne, he came to London."

Her manner of speech was as stately as her person. After each sentence she paused to give Mr Norrell time to be impressed by the information it contained.

"And when my dear Emma is married," she continued, "these paintings shall be my wedding-present to her and Sir Walter."

Mr Norrell inquired if Miss Wintertowne and Sir Walter were to be married soon.

"In ten days' time!" answered Mrs Wintertowne triumphantly.

Mr Norrell offered his congratulations.

"You are a magician, sir?" said Mrs Wintertowne. "I am sorry to hear it. It is a profession I have a particular dislike to." She looked keenly at him as she said so, as though her disapproval might in itself be enough to make him renounce magic instantly and take up some other occupation.

When he did not she turned to her prospective son-in-law. "My own stepmother, Sir Walter, placed great faith in a magician. After my father's death he was always in the house. One could enter a room one was quite sure was empty and find him in a corner half hidden by a curtain. Or asleep upon the sopha with his dirty boots on. He was the son of a leather tanner and his low origins were frankly displayed in all he did. He had long, dirty hair and a face like a dog, but he sat at our table like a gentleman. My stepmother deferred to him in all she did and for seven years he governed our lives completely."

"And your own opinion was disregarded, ma'am?" said Sir Walter. "I am surprized at that!"

Mrs Wintertowne laughed. "I was only a child of eight or nine when it began, Sir Walter. His name was Dreamditch and he told us constantly how happy he was to be our friend, though my brother and I were equally constant in assuring him that we considered him no friend of ours. But he only smiled at us like a dog that has learned how to smile and does not know how to leave off. Do not misunderstand me, Sir Walter. My stepmother was in many ways an excellent woman. My father's esteem for her was such that he left her six hundred a year and the care of his three children. Her only weakness was foolishly to doubt her own capabilities. My father believed that, in understanding and in knowledge of right and wrong and in many other things, women are men's equals and I am entirely of his opinion. My stepmother should not have shrunk from the charge. When Mr Wintertowne died

I

did not."

"No, indeed, ma'am," murmured Sir Walter.

"Instead," continued Mrs Wintertowne, "she placed all her faith in the magician, Dreamditch. He had not an ounce of magic in him and was consequently obliged to invent some. He made rules for my brother, my sister and me, which, he assured my stepmother, would keep us safe. We wore purple ribbons tied tightly round our chests. In our room six places were laid at the table, one for each of us and one for each of the spirits which Dreamditch said looked after us. He told us their names. What do you suppose they were, Sir Walter?"