Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (106 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

"How odd," thought Strange. "And yet of course they would do that. They would do the thing you least expected. Probably it is not Pole's butler at all. Probably it is only a fairy in his likeness. Or a magical illusion." He began to look around for his own fairy.

"Stephen! Stephen!"

"I am here, sir!" Stephen turned and found the gentleman with the thistle-down hair at his elbow.

"The magician is here! He is here! What can he want?"

"I do not know, sir."

"Oh! He has come here to destroy me! I know he has!"

Stephen was astonished. For a long time he had imagined that the gentleman was proof against any injury. Yet here he was in a condition of the utmost anxiety and fright.

"But why would he want to do that, sir?" asked Stephen in a soothing tone. "I think it far more likely that he has come here to rescue . . . to take home his wife. Perhaps we should release Mrs Strange from her enchantment and permit her to return home with her husband? And Lady Pole too. Let Mrs Strange and Lady Pole return to England with the magician, sir. I am sure that will be enough to mollify his anger against you. I am sure I can persuade him."

"What? What are you talking about? Mrs Strange? No, no, Stephen! You are quite mistaken! Indeed you are! He has not so much as mentioned our dear Mrs Strange. You and I, Stephen, know how to appreciate the society of such a woman. He does not. He has forgotten all about her. He has a new sweetheart now – a bewitching young woman whose lovely presence I hope one day will add lustre to our own balls! There is naught so fickle as an Englishman! Oh, believe me! He has come to destroy me! From the moment he asked me for Lady Pole's finger I knew that he was far, far cleverer than I had ever guessed before. Advise me, Stephen. You have lived among these Englishmen for years. What ought I to do? How can I protect myself? How can I punish such wickedness?"

Through all the dullness and heaviness of his enchantment Stephen struggled to think clearly. A great crisis was upon him, he was sure of it. Never before had the gentleman asked for his help so openly. Surely he ought to be able to turn the situation to his advantage? But how? And he knew from long experience that none of the gentleman's moods lasted long; he was the most mercurial being in the world. The smallest word could turn his fear into a blazing rage and hatred – if Stephen misspoke now, then far from freeing himself and the others, he might goad the gentleman into destroying them all. He gazed about the room in search of inspiration.

"What shall I do, Stephen?" moaned the gentleman. "What shall I do?"

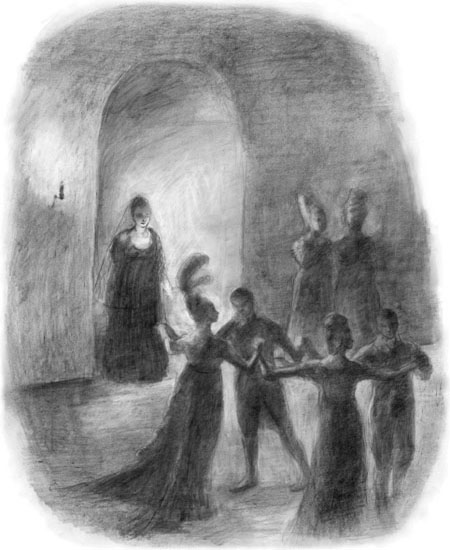

Something caught Stephen's eye. Beneath a black arch stood a familiar figure: a fairy woman who habitually wore a black veil that went from the crown of her head to the tips of her fingers. She never joined in the dancing; she half-walked, half-floated among the dancers and the standers-by. Stephen had never seen her speak to any one, but when she passed by there was a faint smell of graveyards, earth and charnel houses. He could never look upon her without feeling a shiver of apprehension, but whether she was malignant, cursed, or both, he did not know.

"There are people in this world," he began, "whose lives are nothing but a burden to them. A black veil stands between them and the world. They are utterly alone. They are like shadows in the night, shut off from joy and love and all gentle human emotions, unable even to give comfort to each other. Their days are full of nothing but darkness, misery and solitude. You know whom I mean, sir. I . . . I do not speak of blame . . ." The gentleman was gazing at him with fierce intensity. "But I am sure we can turn the magician's wrath away from you, if you will only release . . ."

"Ah!" exclaimed the gentleman and his eyes widened with understanding. He held up his hand as a sign for Stephen to be silent.

Stephen was certain that he had gone too far. "Forgive me," he whispered.

"Forgive?" said the gentleman in a tone of surprize. "Why, there is nothing to forgive! It is long centuries since any one spoke to me with such forthrightness and I honour you for it! Darkness, yes! Darkness, misery and solitude!" He turned upon his heel and walked away into the crowd.

Strange was enjoying himself immensely. The eerie contradictions of the ball did not disturb him in the least; they were just what he would have expected. Despite the poverty of the great hall, it was still in part an illusion. His magician's eye perceived that at least part of the room was beneath the earth.

A little way off a fairy woman was regarding him steadily. She was dressed in a gown the colour of a winter sunset and carried a delicate, glittering fan strung with something which might have been crystal beads – but which more resembled frost upon leaves and the fragile pendants of ice that hang from twigs.

A dance was at that moment starting up. No one appeared to claim the fairy woman's hand, so upon an impulse Strange smiled and bowed and said, "There is scarcely any one here who knows me. So we cannot be introduced. Nevertheless, madam, I should be greatly honoured if you would dance with me."

She did not answer him or smile in return, but she took his proffered hand and allowed him to lead her to the dance. They took their places in the set and stood for a moment without saying a word.

"You are wrong to say no one knows you," she said suddenly. "I know you. You are one of the two magicians who is destined to return magic to England." Then she said, as if reciting a prophecy or something that was commonly known, "

And the name of one shall

e Fearfulness. And the name of the other shall be Arrogance

. . . Well, clearly you are not Fearfulness, so I suppose you must be Arro- gance."

This was not very polite.

"That is indeed my destiny," Strange agreed. "And an excellent one it is!"

"Oh, you think so, do you?" she said, giving him a sideways look. "Then why haven't you done it yet?"

Strange smiled. "And what makes you think, madam, that I have not?"

"Because you are standing here."

"I do not understand."

"Did not you listen to the prophecy when it was told to you?"

"The prophecy, madam?"

"Yes, the prophecy of . . ." She finished by saying a name, but it was in her own language and Strange could not make it out.

4

"I beg your pardon?"

"The prophecy of the King."

Strange thought back to Vinculus climbing out from under the winter hedge with bits of dry, brown grass and empty seed pods stuck to his clothes; he remembered Vinculus reciting something in the winter lane. But what Vinculus had said he had no idea. He had had no notion of becoming a magician just then and had not paid any attention. "I believe there was a prophecy of some sort, madam," he said, "but to own the truth it was long ago and I do not remember. What does the prophecy say we must do? – the other magician and I?"

"Fail."

Strange blinked in surprize. "I . . . I do not think . . . Fail? No, madam, no. It is too late for that. Already we are the most successful magicians since Martin Pale."

She said nothing.

Was it too late to fail? wondered Strange. He thought of Mr Norrell in the house in Hanover-square, of Mr Norrell at Hurtfew Abbey, of Mr Norrell complimented by all the Ministers and politely attended to by the Prince Regent. It was perhaps a little ironic that he of all people should take comfort from Norrell's success, but at that moment nothing in the world seemed so solid, so unassailable. The fairy woman was mistaken.

For the next few minutes they were occupied in going down the dance. When they had resumed their places in the set, she said, "You are certainly very bold to come here, Magician."

"Why? What ought I to fear, madam?"

She laughed. "How many English magicians do you suppose have left their bones lying in this

brugh

? Beneath these stars?"

"I have not the least idea."

"Forty-seven."

Strange began to feel a little less comfortable.

"Not counting Peter Porkiss, but he was no magician. He was only a

cowan

"

5

"Indeed."

"Do not pretend that you know what I mean," she said sharply. "When it is as plain as Pandemonium that you do not."

Strange was once again perplexed what to reply. She seemed so bent upon being displeased. But then again, he thought, what was so unusual about it? In Bath and London and all the cities of Europe ladies pretended to scold the men they meant to attract. For all he knew she was just the same. He decided to treat her severe manner as a kind of flirtation and see if that soothed her. So he laughed lightly and said, "It seems you know a great deal of what has passed in this

rugh

, madam." It gave him a little thrill of excitement to say the word, a word so ancient and romantic.

She shrugged. "I have been a visitor here for four thousand years."

6

"I should be very glad to talk you about it whenever you are at liberty."

"Say rather when

ou

are next at liberty! Then I shall have no objection to answering any of your questions."

"You are very kind."

"Not at all. A hundred years from tonight then?"

"I . . . I beg your pardon?"

But she seemed to feel she had talked enough and he could get nothing more from her but the most commonplace remarks upon the ball and their fellow-dancers.

The dance ended; they parted. It had been the oddest and most unsettling conversation of Strange's life. Why in the world should she think that magic had not yet been restored to England? And what was all that nonsense about a hundred years? He consoled himself with the thought that a woman who passed much of her life in an echoing mansion in a deep, dark wood was unlikely to be very well informed upon events in the wider worlds.

He rejoined the watchers by the wall. The course of the next dance brought a particularly lovely woman close to him. He was struck by the contrast between the beauty of her face and the deep, settled unhappiness of her expression. As she raised her hand to join hands with her partner, he saw that her little finger was missing.

"Curious!" he thought and touched the pocket of his coat where the box of silver and porcelain lay. "Perhaps . . ." But he could not conceive any sequence of events which would result in a magician giving the fairy a finger belonging to someone in the fairy's own household. It made no sense. "Perhaps the two things are not connected at all," he thought.

But the woman's hand was so small and white. He was sure that the finger in his pocket would fit it perfectly. He was full of curiosity and determined to go and speak to her and ask her how she had lost her finger.

The dance had ended. She was speaking to another lady, who had her back to him.

"I beg your pardon . . ." he began.

Instantly the other lady turned. It was Arabella.

She was dressed in a white gown with an overdress of pale blue net and diamonds. It glittered like frost and snow, and was far prettier than any gown she had possessed when she lived in England. In her hair were sprays of some tiny, star-like blossoms and there was a black velvet ribbon tied around her throat.

She gazed at him with an odd expression – an expression in which surprize was mixed with wariness, delight with disbelief. "Jonathan! Look, my love!" she said to her companion. "It is Jonathan!"

"Arabella . . ." he began. He did not know what he meant to say. He held out his hands to her; but she did not take them. Without appearing to know what she did, she withdrew slightly and joined her hands with those of the unknown woman, as if this was now the person to whom she went for comfort and support.

The unknown woman looked at Strange in obedience to Arabella's request. "He looks as most men do," she remarked, coldly. And then, as if she felt the meeting were now concluded, "Come," she said. She tried to lead Arabella away.

"Oh, but wait!" said Arabella softly. "I think that he must have come to help us! Do not you think he might have?"

"Perhaps," said the unknown woman in a doubtful tone. She stared at Strange again. "No. I do not think so. I believe he came for another reason entirely."

"I know that you have warned me against false hopes," said Arabella, "and I have tried to do as you advise. But he is here! I was sure he would not forget me so soon."

"Forget you!" exclaimed Strange. "No, indeed! Arabella, I . . ."

"

Did

you come here to help us?" asked the unknown woman, suddenly addressing Strange directly.

"What?" said Strange. "No, I . . . You must understood that until now I did not know . . . Which is to say, I do not quite understand . . ."

The unknown woman made a small sound of exasperation. "Did you or did you not come here to help us? It is a simple enough question I should think."

"No," said Strange. "Arabella, speak to me, I beg you. Tell me what has . . ."

"There? You see?" said the unknown woman to Arabella. "Now let you and me find a corner where we can be peaceful together. I believe I saw an unoccupied bench near the door."