Johnny Tremain (7 page)

Authors: Esther Hoskins Forbes

Johnny started to look at his hand, but quickly thrust it back in his pocket.

'You're right,' he said. 'I've got to go.'

'I don't want you to feel hurried about leaving us, Johnny. You're just about earning your keep by the odd jobs you do, spite of what Mrs. L. says. You look about you quietly and find a trade to your fancy and a master you think you'd like. You can tell him from me I'll give the rest of your time away for nothing.'

It was less than two months ago Mr. Revere was promising something extra for his time.

'Mrs. L. doesn't like it the way you loiter off and go swimming; but you loiter and swim all you have a mindâjust so you get the chores done and settle down real hard to finding yourself a new trade. And one more thing I have on my mind.'

'Yes, sir.'

'I want you to forgive Dove like a Christian.'

'Forgive him? Why?'

'Why, that when you asked for a crucible he handed you the old cracked one.'

'You mean ... he did it on purpose?'

'No, no, Johnny, he only meant to humiliate you. He tells me (Mrs. L. made me question him) that he was that offended by your Sabbath-breaking he thought it fitting that you should learn a lesson. I can't help but admit I'm encouraged with that much piety in

one

of my boys.'

Johnny's voice sounded strangled. 'Mr. Lapham, I'm going to get him for that...'

'Hush, hush, boy. I say, and Bible says, forgive. He was real repentant when he told me. Never meant to harm you. He was in tears.'

'He's going to be in a lot more of those tears 'fore I'm done with him. That scabby, white louse, that hypocritical...'

'Hold your tongue, boy. I thought misfortune had taught you patience.'

'It has,' said Johnny. 'If I have to, I'll wait ten years to get that Dove.'

But he quieted himself instantly and thanked his master for his kindness. As he walked past the shop, he saw Dove and Dusty hanging idly out of the shop window. They were looking for him.

Dove said: 'Will Mr. Johnny Tremain be so kind as to fetch us drinking water? Mrs. Lapham says

we

are too valuable to leave our benches. She told us we were to send you.'

Without a word he went to the back entry, put on the heavy yoke.

Understandably, the sight ofJohnny wielding a broom, carrying charcoal, firewood, water, had not quickly lost its fascination for his erstwhile slaves. They were still hanging out of the window.

'Look sharp, Johnny.'

'Hey, boy, look sharp.'

Giggles. A low whistle.

Johnny said nothing.

W

EEKS

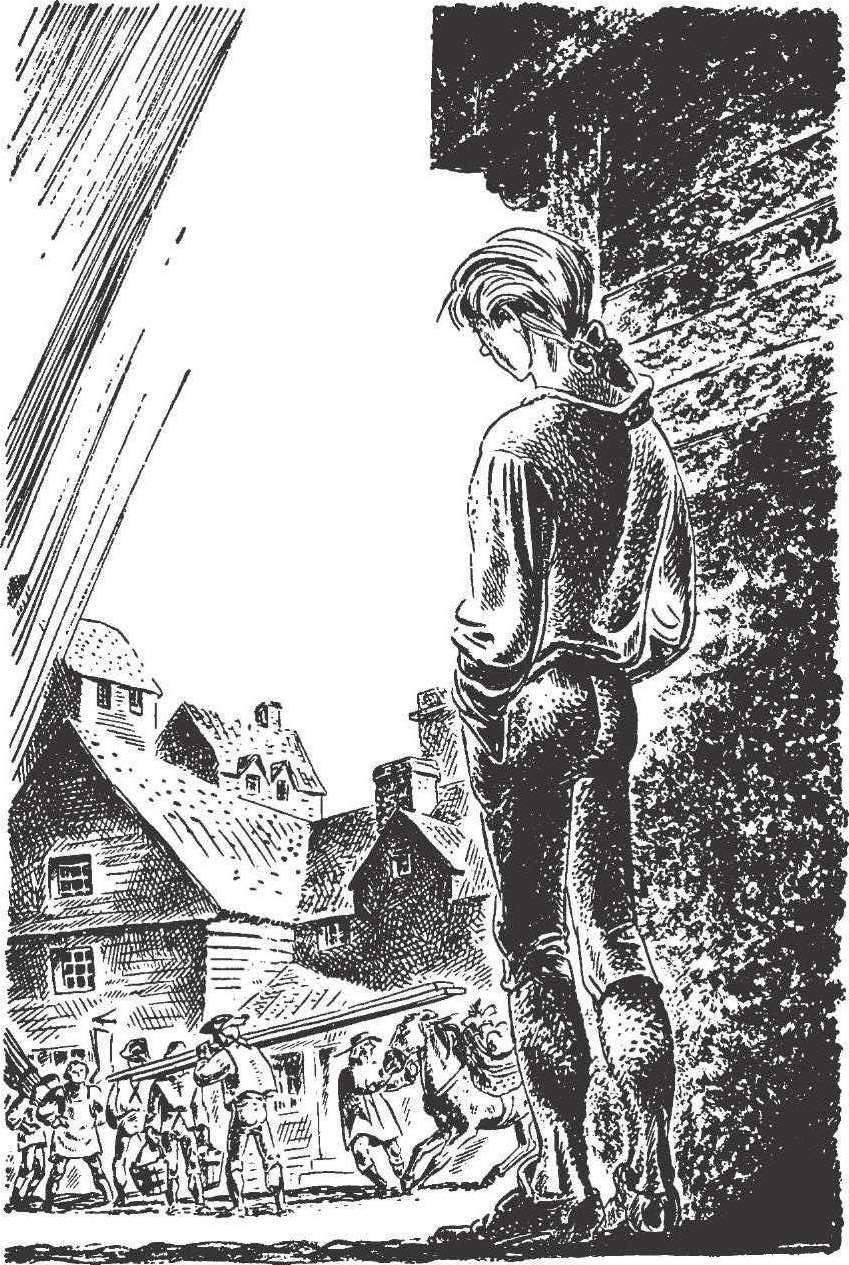

wore on. September was ending. A large part of every day Johnny spent doing what he called 'looking for work.' He did not really want to follow any trade but his own. He looked down on soap-boilers, leather-dressers, ropemakers, and such. He did not begin his hunt along Hancock's Wharf and Fish Street, where he and his story were well known and the masters would have been apt to employ him from pity. He went to the far ends of Boston.

Mr. Lapham had told him to stand about and watch the different artisans at their trades until he was sure it was work he could do. Then he was to address the master politely, explain about his bad hand, and ask to be taken on. But Johnny was too impatient, too unthinking and too scornful. He barged into shop after shop along the great wharves and up and down Cornhill and Orange, Ann, and Ship Streets, Dock Square, King and Queen Streetsâ'Did the master want another boy?'âkeeping his hand hidden in his pocket.

His quickness and address struck everyone favorably, and so an old clockmaker eagerly agreed to take him onâespecially when he told him that he had already served Mr. Lapham two years.

'But why, my boy, is Mr. Lapham ready to part with you, now that you must be of value to him?'

'I've a bad hand.'

'Let me see it.'

He did not want to show his hand, but the masters always insisted. He would take it out of the pocket where he always kept it, with a flourish, display it to the sickening curiousity of the master, apprentices, journeymen, lady customers. After such an experience he would sometimes loiter and swim for the rest of the day. Sometimes he would grit his teeth and plunge headlong into the next shop.

He rarely bothered to look at the signs over the door which indicated what work was done inside. A pair of scissors for a tailor, a gold lamb for a wool weaver, a basin for a barber, a painted wooden book for a bookbinder, a large swinging compass for an instrument-maker. Although more and more people were learning how to read, the artisans still had signs above their shops, not wishing to lose a possible patron merely because he happened to be illiterate.

Having been told by one clockmaker he would not suit, Johnny walked in on two more and got the same answer.

A butcher (his sign was a gilded ox skull) would have employed him, but the idea of slaughtering animals sickened him. He was a fine craftsman to the tips of his fingersâeven to the tips of his maimed hand.

Now he never came home for the hearty midday dinner. Mrs. Lapham, Madge, and Dorcas were always pointing out how much he ate and how little he did. He knew Mrs. Lapham was looking around for a grown-up silversmith who would come in as a partner for Grandpa, and she had said (looking straight at Johnny) she would not ask him to sleep in the attic with the two boys. He was to have the birth and death room. 'I declare,' she said one day, 'no business can be run with just a feeble old man and three of the most worthless boys in Bostonâeating their heads off.'

Seems she was negotiating with a Mr. Tweedieânewly arrived from Baltimore. He had arrived alone, but she must make sure he really was a bachelor or a widower. Obviously, whatever partner she found for her father-in-law must marry one of her 'poor fatherless girls.' The shop must stay in the family.

So Johnny ate as little as he could, and did not come home at noon. But someone would usually slip a piece of hard bread, cheese, jerked beef, or salt fish and johnnycake in the pocket of his jacket as it hung on its hook. He knew it was Cilla, but he never spoke to her about it. His unhappiness was so great he felt himself completely cut off from the rest of the world.

But sometimes, as he lay in the sun on Beacon Hill or Copp's Hill (among the graves), or curled himself upon a coil of rope along a wharf, eating the food she had managed to get for him, he would dream of the great things he would do for herâwhen he was man-grown. There were three things she longed forâa gold necklace; a gray pony with a basket cart; a little sailboat. He dreamed of himself as successfulârich. Never as the ditch-digger and ragpicker Mrs. Lapham was always suggesting to him.

Some days there was no food in his pocket. Then he went hungry.

On one such day, he was strolling up Salt Lane. Here about him and on Union Street were printing offices. It was noon, and all over Boston work had stopped and everyone, except himself, had either gone home for dinner or to one of the famous taverns. Above one tiny shop he saw a sign that attracted him. It was a little man in bright blue coat and red breeches, solemnly gazing at Salt Lane through a spyglass. So this was where the

Boston Observer

was published. The Laphams took no newspaper, but he had heard Mr. Lapham speak of the wicked

Observer

and how it was trying to stir up discontent in Boston, urging the people to revolt against the mild rule of England. The comical little painted man looked so genial, so ready to welcome anyone, that Johnny stepped in.

He might have guessed he would waste his time. Of course the master would be off for dinner, but because he had liked the painted sign, he went in. He had not even stopped to consider whether or not a printer's work was something that he could do.

He saw the squat, buglike printing press, the trays of type, the strings on which printed sheets were hung to dry like clothes on a line. On a workbench was a smaller press for notifications, proclamations, broadsides, trade cards. Everything smelled of printers' ink.

A boy, larger than himself and probably a few years older, was standing at a counter talking with a stout marketwoman in a frayed red skirt. Her pig had strayed from her yard. She wished to advertise it. The boy wrote down what she said.

'Lostâa spotted sow from Whitebread Alley,' the boy repeated.

'She was the

dearest

pig,' said the womanâ'would come for a whistle like a dog. My children taught her to play "dead pig." We don't ever think to eat herâonly her increase. We called her Myra.'

The boy did not write that down. He lifted his dark face, indolent dark eyes. The lashes flickered. He was interested.

'Was she hard to teach, ma'am?'

'Oh, no! Pigs are clever.'

'I never knew that. How do they compare with dogs?'

Then the old lady began to talk. She talked about pigs in general and her Myra in particular.

The printer's boy, unruffled, unhurried, heard her through. He was tall and powerfully built. There was something a little sluggish in his casual movements, in his voiceâalmost as though he was saving himself for emergencies, not wasting himself on every casual encounter.

The woman was delighted with so good a listener and his few intelligent questions. Johnny, standing at the door, forgot his own errand. He had no idea that either pigs or old market-women could be so interesting. It was the apprentice, standing at the counter in his leather apron and full white shirt, his thoughtful face framed in hair, black and straight as an Indian's, who had cast a spell over the old gossip and her subject.

Although the boy had nodded casually as Johnny came in, he did not speak to him until after the woman was gone and he had set up the few lines of type. There was nothing rude about this seeming neglect. It was almost as if they were friends of long standing. The strange boy had none of the bustling smartness of the usual Boston apprentice. Johnny had seen enough of them in the last month, apprentices who knew what you wanted and that you would not suit, and you were out on the street again in three minutes.

Having set the advertisement, the boy took a covered basket from under the counter, put it on a table, and drew up two stools.

'Why don't you sit down?' he said, 'and eat. My master's wifeâshe's my auntâalways sends over more than I can manage.'

Seemingly he had sized up everything with only half a glance from the lazy, dark eyes. He had known Johnny was hungry without once really looking at him and had also known that he was someone he himself liked. He was both friendly and aloof. Nonchalantly he took out his claspknife, cut hunks of bread from the long loaf. There were also cheese, apples, and ham.

The ham seemed to remind the printer's boy of the gossip and her pig.

'I grew up on a farm,' he said, 'but I never knew you could teach a pig tricks. Help yourself to more bread?'

Johnny hesitated. So far he had not taken his bad hand out of his pocket since entering the shop. Now he must, or go hungry. He took the claspknife in his left hand and stealthily drew forth the maimed hand to steady the loaf. It was hard to saw through the crusty loaf with a left hand, but he managed to do it. It took him a long time. The other boy said nothing. He did not, thank God, offer to help him. Of course he had seen the crippled hand, but at least he did not stare at it. Asked no questions. Seemingly he saw everything and said nothing. Because of this quality in him, Johnny said:

'I'm looking for some sort of work I think I could do well in ... even with a bad hand.'

'That's quite a recent burn.' It was the first intelligent remark any man, woman, or child had made about Johnny's hand in any shop he had been in.

'I did it last July. I am ... I

was

apprenticed to a silversmith. I burned it on hot silver.'

'I see. So everything you are trained for is out?'

'Yes. I wouldn't mind so much being a clockmaker or instrument-maker. But I can't and I

won't

be a butcher nor a soap-boiler.'

'No.'

'I've

got

to do something I like, or ... or...'