Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle (25 page)

Read Jerry Langton Three-Book Bundle Online

Authors: Jerry Langton

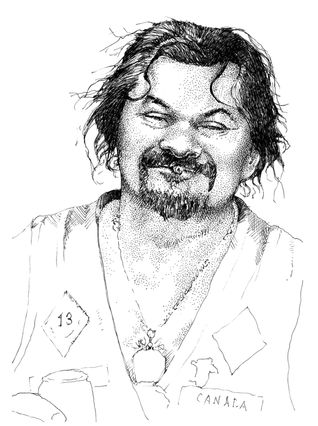

Every day, on their way to and from elementary school, Giovanni Muscedere and his little brother Joe were bullied. Their family had recently emigrated from Italy to Windsor and the boys still didn't speak English all that well. Some of the area's other boys thought the Muscederes' attempts at communicating in their new language was comical, so they teased them. After a while, the teasing became verbal abuse, and that evolved into physical assaults.

After being beaten up a couple of times, Giovanni Muscedere vowed to his little brother that he would never lose a fight again, no matter how big or how many his enemies were. He learned to box, he worked out. He grew big, strong and fearless. He stopped calling himself Giovanni, and switched to John. John Muscedere turned the tables on his bullies and then became something of a bully himself.

Years later, Muscedere lived in Chatham â about an hour's drive east on the 401 from Windsor, halfway to London â and had a steady job as a forklift operator at the Rockwell International (later renamed ArvinMeritor) brake plant in Tilbury, about halfway between Chatham and London. He was a jolly guy who made friends easily and liked to party. He also taught kids how to box, earning him the nickname “Boxer” among his friends.

Giovanni Muscedere

He was also a biker. Muscedere originally ran with a low-level gang called the Annihilators. Based in a lonely little shack in a hamlet called Electric about 20 minutes northwest of Chatham and not far from Sarnia, the Annihilators were big-time partiers and small-time crooks. Muscedere himself had gotten into some trouble with break-and-enter charges and the odd assault.

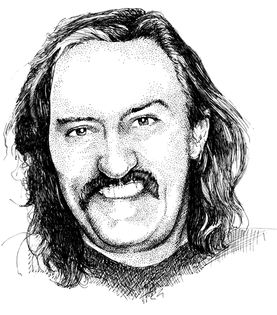

But his rap sheet paled in comparison to his old friend and Annihilators president â Wayne “Weiner” Kellestine. Although he was first arrested many years earlier, Kellestine began to enter law enforcement's collective consciousness in a serious way in 1982. At the trial of another man, a witness testified that it was common knowledge that Kellestine had murdered a man named John DeFilippo and wounded his father-in-law Vito Fortunato in a Woodbridge home invasion back in 1978. Police investigated, but couldn't muster enough evidence to bring charges against Kellestine.

A couple of years later, Kellestine was charged with assault after he punched a bouncer who was trying to eject one of his friends from a London bar. He paid a $700 fine. Months later, police found $325,000 worth of cocaine and LSD and a semiautomatic handgun on Kellestine's farm in Iona Station, a village not far from London. But again, they couldn't build enough of a case to lay any serious charges.

Kellestine kept out of serious trouble until December 1991. On a cold morning, a black SUV screeched to a halt in front of the emergency admitting entrance to the Elgin General Hospital in St. Thomas. A rear door opened and a body wrapped in a blanket was thrown out of the vehicle. EMTs rushed the man inside and hours of surgery saved his life as surgeons took four bullets out of his gut.

Wayne “Weiner” Kellestine

The man was 34-year-old Thomas Harmsworth. He was a full-patch Outlaw who came from Iona Station, the same 300-resident hamlet just west of St. Thomas that had produced one of the 20

th

century's greatest minds â economist John Kenneth Galbraith â and, more dubiously, Wayne Kellestine.

th

century's greatest minds â economist John Kenneth Galbraith â and, more dubiously, Wayne Kellestine.

Once he was conscious, police questioned Harmsworth. But he refused to speak. If he knew who shot him, he wasn't saying. The cops proceeded to investigate without his cooperation, but quickly abandoned the case in January 1992.

The official reason was a lack of evidence â which was completely plausible since Harmsworth wouldn't talk â but others in the area had a very different opinion. A couple of sources I spoke with said that the cops knew Kellestine was behind the shooting, but they made a sweetheart deal with him.

Just two days before they officially dropped the Harmsworth case, police announced they had found the body of David McNeil in a shallow makeshift grave on a lonely country road just outside another nearby village named Dutton. His corpse had three holes in the back of its skull, the result of three .38-caliber bullets fired at extremely short range.

McNeil had been wanted for the September 19, 1991 murder of an Ingersoll police officer named Scott Rossiter. While nobody has come out â even off the record â to tell me that Kellestine killed McNeil, the consensus among the cognoscenti in Southwestern Ontario is that Kellestine at least knew of McNeil's death and led the cops to his body in exchange for a quick end to the Harmsworth investigation.

Two months after the McNeil incident, local police forces and the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) mounted Project Bandito (this was long before the Texas-based Bandidos had any presence in the country, so the name is just a coincidence), in which more than 100 officers raided the clubhouses of the Outlaws and Annihilators, along with the residences of many of their members, prospects and associates.

Kellestine was caught red-handed. When police broke into his house, he was passed out on his living room couch, surrounded by drugs, cash and weapons. And there was an unregistered, semiautomatic handgun within his arm's reach.

Faced with mountains of evidence â including videotape of him selling cocaine, ecstasy and a handgun to an undercover cop â Kellestine pleaded guilty. He was given six years.

It is a custom in the Canadian correctional system to release prisoners after two-thirds of their sentence unless there are some extenuating circumstances. The parole board twice denied Kellestine's bids to leave prison before his six years were up, citing his continued association with “known and active criminals” and for failing mandatory drug tests while in custody.

Things shifted in the Ontario outlaw biker environment while Kellestine was in prison. Changes in Toronto reverberated through the rest of the province, and the southwestern corner was no different.

After the Loners won the great Toronto biker war of 1995 against the Diablos, they split into two distinct pieces. One was absorbed by the Hells Angels-aligned Para-Dice Riders, while the other stayed nominally independent.

Kellestine â eager to be on the side against Hells Angels but reluctant to align directly with the Outlaws â accepted the Loners' offer of a patch-over. The Annihilators ceased to exist. Although police and the media generally refer to this new chapter as the St. Thomas or London Loners â perhaps because most of the members lived in or around the city â they always identified themselves as being the Chatham Chapter. Soon thereafter, the Loners established another, smaller chapter based in Amherstburg â a small town just south of Windsor.

Things got complicated after that. The London Outlaws fought a small and largely indecisive war with Coates' Hells Angels. Two Hells Angels operatives had tried and failed to assassinate Kellestine, probably in an effort to bring them into the war as well.

The Rock Machine â supported by the Texas-based Bandidos â set up three chapters in Canada. Then on December 29, 1999, Stadnick pulled off his massive Ontario patch-over, in which all kinds of bikers â the Para-Dice Riders, the Vagabonds, Satan's Choice, Iron Hawgs and others, even a few Outlaws â became Hells Angels. Many observers in the media and law enforcement were aghast. “They were truly scraping the bottom of the barrel,” one cop I know told me. “They were trading patch-for-patch the legendary Hells Angels patch for some of the lowest of the low.”

But still, the remaining Loners who had not joined the Para-Dice Riders were among the few gangs in Ontario not offered Hells Angels patches. The Woodbridge Loners continued to survive as a nominally independent but, in practice, pro-Hells Angels club. The next time they made news was in January 2001, when the club attempted to keep its mascot â an 800-pound, neutered, declawed lion named Woody â on a farm north of the city in the face of widespread protests.

The Chatham Loners, however, were another story. Because of Kellestine, Hells Angels wanted no part of them. Instead, they, along with the Rock Machine chapters in Toronto and Kingston, became a prospective Bandidos chapter.

Like many motorcycle clubs, Bandidos were formed by a man who admired Hells Angels, but couldn't join them. Bandidos formed in 1966 in the Southeastern Texas town of San Leon when a longshoreman and former U.S. Marine named Donald Eugene Chambers met a fellow dockworker who had been with Hells Angels in upstate New York. Despite the number of ports there and the proximity to Mexico, there was virtually no Hells Angels' or Outlaws' presence on the Gulf Shore of Texas.

The gang took off very quickly. Bandidos took over the region, and expanded rapidly, attracting Vietnam veterans the same way Hells Angels and the Outlaws had veterans of World War II and the Korean War a generation or two earlier. It has frequently been reported in the media that Chambers, a Vietnam combat veteran, took the name and look from the Frito Bandito, a cartoon mascot the Frito-Lay company used to sell its corn chips, but that logo actually debuted in 1968, well after the club's formation.

By the time Stadnick conquered Ontario, Bandidos had eclipsed the Outlaws as the second most powerful biker gang in the world, behind only Hells Angels themselves. They had a few advantages. While Hells Angels have a strict whites-only rule (the Outlaws' views on this vary from chapter to chapter and country to country, but they are still overwhelmingly white), Bandidos readily welcomed some non-whites, and are very heavily Hispanic or even predominantly Muslim in some areas. And while Hells Angels do have many foreign chapters, Bandidos have been far more aggressive when it comes to recruiting overseas.

And it was actually from Sweden that the first Bandidos' presence came to Canada. In the late 1990s, when the Rock Machine was losing what had become a very one-sided war against the Hells Angels in Quebec, a high-ranking member of the Rock Machine named Fred Faucher asked the Swedish Bandidos for help.

He was impressed by what the Scandinavian Bandidos had accomplished in what the media called “The Great Nordic Biker War.” In a battle waged from 1994 to 1997, Bandidos (along with a few Outlaws and smaller clubs) managed to fight Hells Angels and their allies to a stalemate. Although there were far fewer casualties â 12 deaths (including one innocent civilian) and 96 wounded â than in the Quebec Rock Machine-Hells Angels war, the conflict in Scandinavia made more headlines worldwide. That was probably because the war crossed international borders â Sweden, Denmark and even Finland were involved â and because the bikers (many of whom had ties with their countries' militaries and/or white supremacist groups) used machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades to settle their differences. It got so bad, in fact, that the Danish government actually passed a law forbidding biker gangs from buying or renting property as clubhouses. The law was later overturned as unconstitutional, but it lasted long enough to make a big difference. The Bandidos and Hells Angels even signed a truce in Denmark, live on national television.

The European Bandidos â especially in France, a place where Bandidos are quite strong â welcomed the Quebeckers with open arms. But things were different with their bosses down in Texas who had the final say on everything. At first the Texans weren't crazy about the idea of the Rock Machine. They knew little about Quebec, the war with the Hells Angels or the gang itself. But when some arrests and casualties led to Faucher becoming acting president of the Rock Machine by default, he invited Bandidos from around the world to a huge party in Quebec City, and things quickly changed. The Rock Machine may have ceased to exist, but it wasn't because of the Hells Angels. Instead of surrendering, Faucher and his men wanted to get stronger.

It happened, appropriately enough, in Woodbridge, a town best known for its Mafia connections. In recent years, it had been home to at least three separate incarnations of the Loners, the Diablos, Satan's Choice, the Para-Dice Riders, the Rock Machine, Hells Angels and, now, Bandidos. The Rock Machine negotiated with Bandidos, and the patch-over was official.

Other books

Hearts Evergreen: A Cloud Mountain Christmas\A Match Made for Christmas by Robin Lee Hatcher

A Bid for Love by Rachel Ann Nunes

The Witchfinder by Loren D. Estleman

Bone And Cinder: A Post-Apocalyptic Thriller (Zapheads Book 1) by Nicholson, Scott, Simcox, Joshua

Nicademus: The Wild Ones by Sienna Mynx

A Touch of Crimson by Sylvia Day

Cassie's Hope (Riders Up) by Kraft, Adriana

Found Guilty at Five by Ann Purser

Children of the Knight by Michael J. Bowler

Love Beat by Flora Dain