January (15 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Lord

‘My mum won’t quit hassling me about it. It’s been on the news again, and look here …’ He pulled his mobile and passed it to me. I snatched it.

‘Great,’ I said, handing the mobile back. ‘I’ve always wanted to get my name in the headlines.’

‘Even Mr Lee, from school, was on the news!’ said Boges. ‘He was crapping on about how you’d always been popular, a good kid and a good student, and that he was shocked and

devastated

to hear you were involved in the attacks. Then Susie Miller jumped in beside him and said something like, “Yeah, me and Cal dated in, like, Year 8, and I just feel so lucky that the relationship, like, ended when it did. It could have turned real ugly.”’ Boges laughed. ‘She’s the only thing that’s turned ugly!’

What could I say? The situation was ridiculous. I couldn’t believe that I was going to have

to convince my mum that I had nothing to do with what had happened.

Boges had brought me more food and drinks: water, bread, a few tins of baked beans, some chips and chocolate.

Rations.

I grabbed a bag of chips and pulled the drawings out of my backpack, spreading them out on the floor.

‘Your dad sure could draw,’ said Boges after a while. ‘Look,’ he said. ‘Another angel.’

It was the second drawing of the commando angel—he was smaller than the one I already had, but wearing the same World War I tin hat, and the same gas mask around his neck.

‘Was your dad religious?’ Boges asked, staring at the figure of the angel.

‘He didn’t go to church,’ I said, ‘if that’s what you mean.’

I recalled conversations I’d had with Dad, especially out in the boat—we’d talk about the hugeness of the ocean and the sky, the sun blazing over the dark blue sea, and the gulls hanging on the wind. Maybe, Dad said, we can expand our minds like the expanding universe we live in. He said that life was his religion. You needed to live it well and honestly, being grateful for whatever came along, because everything that happened was life happening, whether we liked it or not. I wasn’t too sure that I understood him.

‘Why would he draw an angel then?’ Boges asked, ‘And to draw him twice?’

I looked closely at the angel’s unsmiling face. He didn’t actually look stern, like I’d thought at first. It was more the look of someone who didn’t have any time to waste.

Someone on a mission.

‘The doctors told me that Dad’s mind could only work around or near the ideas he was trying to draw.’

‘You mean by drawing an angel he might have meant the devil?’

I shook my head. ‘No. It wasn’t opposites. It was more of a

close to

.’

‘OK,’ said Boges, tapping on the next drawing. ‘What do you make of this one?’

It was a picture of a waiter, wearing a bowtie and carrying two playing cards on a tray—an ace of hearts and a jack of clubs.

‘Did your dad play cards?’

‘Sometimes,’ I said, ‘we’d sit around in the summer holidays at the beach house playing board games and the occasional game of cards.’

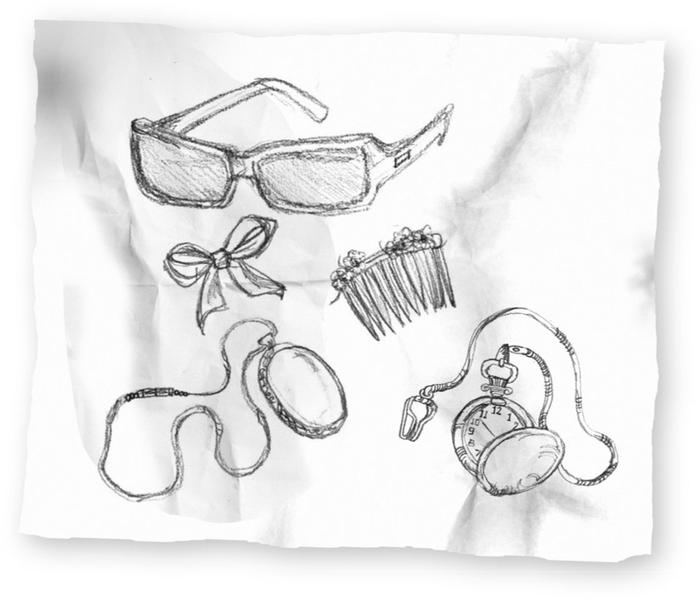

The third drawing was a collection of smaller, odd sketches. It looked like Dad had just been doodling, trying his hand with various objects. There was an old-fashioned watch on a chain, a pair of sunglasses, a ribbon tied in a bow, some flowers attached to a hair comb and something that looked like a medallion on a chain. All I could make out on the medal was some decorative leaves and scrolls around its edges.

We turned to the next picture—a white-looking monkey with a fancy collar around its neck, and a fancy ball in its hand.

‘Why would he draw that?’ Boges asked. ‘And this one,’ he said picking up the fifth drawing.

I took it from him, studying it close. It was a sketch of the Sphinx from Egypt, crouching in the sands, staring blindly from its blunt, eroded face.

‘Did your dad ever work in Egypt?’ Boges asked.

‘I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘I don’t remember him ever talking about Egypt.’

In front of the Sphinx, almost directly in the middle of the huge figure’s granite lion paws, there was the bust of some Roman guy.

‘So who’s this supposed to be?’ he asked. The figure looked serious, and had the folds of a toga over his shoulder.

‘No idea. A Roman emperor?’

‘And this one?’

Boges pointed to another drawing, a child with a rose.

I shook my head again.

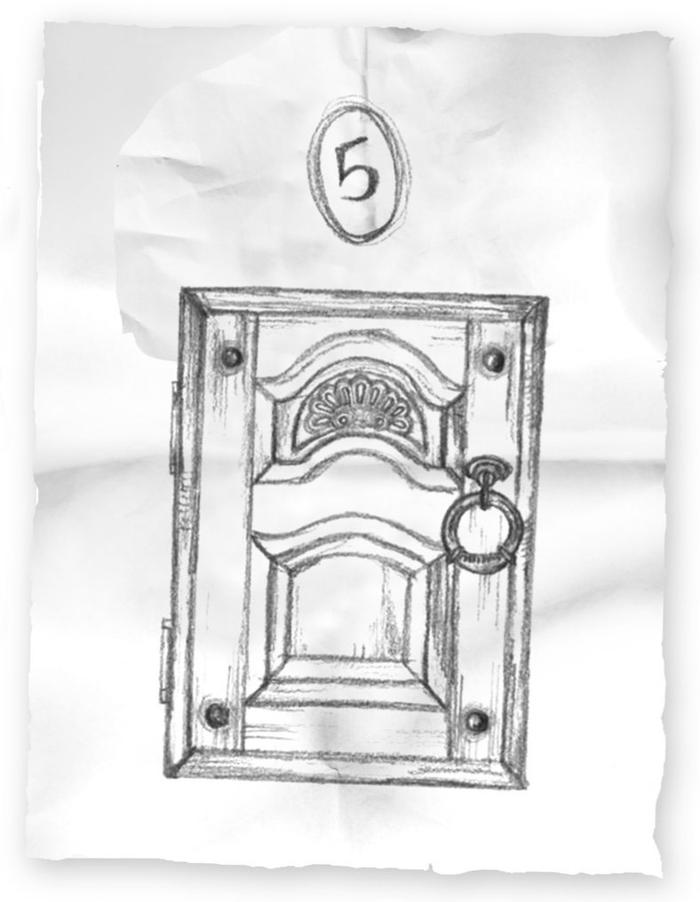

The last drawing looked like an

old-fashioned

cupboard door, with some fancy carving on the top and a great big metal ring at the front. At the top of the drawing was the number five in an oval.

‘Mean anything to you?’ Boges asked.

‘Nup.’

‘What about the number five?’

‘Nup.’

‘This one with all those odd things on it—the watch, the ribbon, the sunglasses, the medal thing, the comb—reminds me of one of those “what-do-all-these-things-have-in-common” kind of intelligence tests.’

‘You’re right,’ I said, grabbing the drawing from him. ‘Even though they’re all different, they’re all things that people can wear. So what do you think it means?’

‘Actually,’ said Boges after a pause, ‘I don’t know.’

I punched his arm and laughed. ‘Well we have to work out what they mean. We’ve already made a start.’

I remembered the time Dad’s old wind-up clock crashed from his desk and burst open, scattering screws, metal plates, little gear wheels, its hands and a long, blue-black springy coil. Dad’s drawings were probably like that. Crazy random images, exploding out of a

breaking-

down mind.

I felt that Dad was still here, in his drawings, talking to me, sending me his messages. But would I be smart enough to work them out? That was the part I wasn’t sure about. Even with Boges’s help I was sure it was going to be a tough job.

‘Rafe is going to find out they’re missing next time he goes to the mausoleum,’ I said.

‘I’ve already thought of that,’ said Boges. ‘He’s going to think he’s lost the key first. Then he is going to have to get a new one. That gives us a bit of time before he realises they’re missing. And then, we know that at least one other party is after them. Your kidnappers.’

‘You think he might believe that the woman and her mates have got hold of them?’