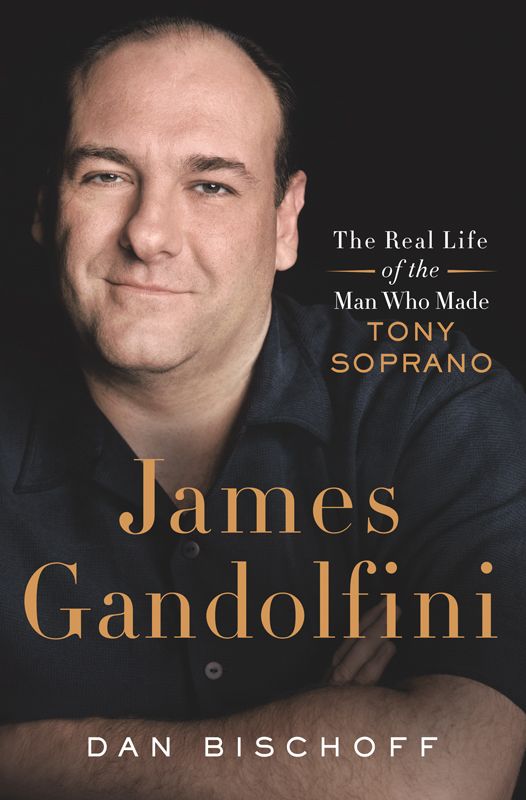

James Gandolfini: The Real Life of the Man Who Made Tony Soprano

Read James Gandolfini: The Real Life of the Man Who Made Tony Soprano Online

Authors: Dan Bischoff

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For my mother, Rose Mary Maher Bischoff

Contents

5.

Character Actor Years: Working-Class Hero vs. Gentle Hitman

7.

Troubles on the Set (2000–2003)

8.

The Pressures of Success (2003–2007)

9.

After T

10.

Beloved

11.

Gotta Blue Moon in Your Eye

Acknowledgments

I undertook this book almost overnight, and it would never have seen the light of day without the kind ministrations of my agent, Scott Mendel, whose inspiration started it all. My editor, Elizabeth Beier, provided crucial enthusiasm for the topic and has always been understanding about every deadline, while Michelle Richter made sure I crossed every elastic line on time.

This book would also not be here without the attention of Meryl Gross, production editor at St. Martin’s, or the help provided by publicist Katie Bassel and marketing experts Erin Cox and Angie Giammarino. Steven Seighman designed the interior, and the cover was put together by Rob Grom.

This book was not written with the official cooperation of the Gandolfini family and reflects my conclusions, not theirs. Yet the loyalty James Gandolfini engendered in those who knew him, like high school teacher Ann Comarato, fellow student Donna Mancinelli, and Park Ridge mayor Don Ruschman, tells us a lot about his character. Mark Di Ionno’s sharp understanding of New Jersey’s social landscape was as important as his assessment of his college buddy’s nature, and few have a subtler feeling for the artist his friend would become than T. J. Foderaro. Skylar Frederick, the graduating editor of

The Daily Targum,

the campus newspaper at Rutgers University, helped check stories for me in campus files, a courtesy for which I’m very grateful. The professional acumen of actor Roger Bart, and of course that of Gandolfini’s first professional acting teacher Kathryn Gately, were invaluable; and Gandolfini’s coach, collaborators, and friends Harold Guskin and Sandra Jennings, were as generous with their experience as anyone could be. The man many people called Jim’s best friend, once a sportswriter for

The Daily Targum,

a fellow bouncer at the campus pub, a manager at Bell Labs, and ultimately an executive at Attaboy Films, Tom Richardson was an unfailing gentleman at every turn.

Susan Aston was part of Gandofini’s personal and professional life longer than anyone, and her wry but sweet realism is the finest praise a subject could want.

Gandolfini’s managers Mark Armstrong and Nancy Sanders were essential to telling the story of the actor’s life in Hollywood, and Angela Tarantino of HBO was unfailingly helpful. Tony Sirico and his pal Al Giordano of Wounded Warriors care a great deal about their friend’s commitment to the generation that came home from war without a G.I. Bill. And the thoughtful generosity of Nicole Holofcener and Michaël Roskam, the directors of Jim’s two posthumous films, was very welcome. The work of so many fine journalists from Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz to Peter Biskind and Chris Heath informed every page. My colleagues at

The Star-Ledger,

in particular my editor Enrique Lavin and librarian Giovanna Pugliesi, extended a cooperative understanding for which I’ll always be grateful.

More personally, I have to thank Marc Cooper and Natasha Vargas-Cooper, whose crucial help at a key moment made the book possible. Maria Laurino started me off with a characteristically perceptive analysis of Italian-Americans in New Jersey, her own specialty. I should close with the names of all those friends and colleagues whose support over the course of the book was important to me in more ways than I can describe here: Peter Kwong and Du

š

anka Mi

šč

evi

ć

, Allen Barra and Jonelle Bonta, James and Pat Ridgeway, Chuck and Ires Wilbanks, Will Rosenthal, Emily Hubley, Martha Elson, Pate Skene, Willie Neuman, Andie Tucher, and so many more I’m surely being churlish to forget. My good friend Kevin Jon Klein, a playwright and professor of screenwriting at Catholic University, happily acted as a sounding board for many of the ideas presented here (so anything that’s wrong is partly his fault).

Finally, my family, my sister, Kathy, and my brother, John, and of course my son, Boone, are the reasons this book was written. I hope they know how much I’ve always appreciated their support. My wife and fellow writer, Leslie Savan, who provided a second pair of eyes for every word you find here, knows for sure.

1.

All Roads Lead to Rome

It was not unlike the way

The Sopranos

ended, in Holsten’s ice cream parlor in Bloomfield, New Jersey: One minute Tony’s changing the jukebox to Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’,” waiting for his daughter, Meadow, to join the rest of the family for onion rings. And then, fade to black.

Only this time, the restaurant was in a five-star hotel in Rome, built on third-century Roman ruins across the street from a church Michelangelo designed for the last intact ancient

tepidarium,

in the Baths of Diocletian. James Gandolfini was in Italy with his son, Michael, on vacation. They’d arrived on the twelve-hour flight from Los Angeles the night before, and had just had “a beautiful day” sightseeing. Jim told friends he’d been looking forward to a “boys’ trip,” where he and Michael, thirteen, could explore their Italian heritage together—it was something Tony Soprano had said he wanted to do after touring Naples in the second season, let his kids see “all this stuff they come from.”

In the afternoon, he took Michael to the Vatican. He bought a couple of rosaries for his sisters, blessed by Pope Francis and promising indulgences, the proceeds dedicated to the convent that works for Rome’s poor. Then they went to the Musei Vaticani to see, among much else, the mummies and sarcophagi in the Ancient Egyptian galleries. They were photographed there standing between two illustrated coffin lids by a pair of American tourists from Philadelphia.

They left the Vatican in the middle of one of those Roman afternoons in June when the rooflines waver in the sun and the fountain spray evaporates before it hits the pool. They were waiting for James’s sister Leta, who was arriving from Paris that night after meetings with her dress company, American Rag. They were going to enjoy a few days in the curving Boscolo Hotel Exedra on the Piazza della Repubblica until Jim made a scheduled appearance at the Taormina Film Fest in Sicily, where he’d do an appearance with an old castmate, Marisa Tomei.

It was just James and Michael that night in the hotel’s outdoor restaurant, still trying to get past the jet lag and fall into sync with Italian time. They ate, lingered over drinks and dessert, and started drifting up to their room around 9:00

P.M

.

And then, fade to black.

At least, that’s how it felt to many. Michael found his father on the floor of the bathroom in their suite at around ten that night and called the desk for help. An emergency crew from the nearby Policlinico Umberto I was there in minutes; Gandolfini was still alive, even as they wheeled him, bare-chested and wrapped in a hotel blanket, out through the lobby. He died at the hospital of cardiac arrest, after continuous resuscitation efforts, forty minutes later. He was fifty-one years old.

At first, the world reacted the way so many had to the end of

The Sopranos

—with absolute shock. Then the cascade of regrets, well-wishes, and sorrow for an actor who made millions sympathize with a stone-cold killer for almost ten years, becoming part of the American family. Everyone expected many more years, and many more characters, each one subtly reshaping the working-class hero he’d become—such as

Enough Said,

a romantic comedy with Julia Louis-Dreyfus for Fox Searchlight, expected for 2014 (the company would put it into quick turnaround after Gandolfini’s death), about a woman who falls in love with her friend’s husband. Slowly, the realization sunk in that this fade-out meant something else—there would be no

Sopranos

movie.

Ever since “Don’t Stop Believin’” went into its last verse in that Bloomfield ice cream parlor, every fan of

The Sopranos

had been asking when their favorite mob family would get its big-budget,

Godfather-

type, silver-screen treatment, as if that would somehow be better. Gandolfini had been asked about it just a few days before he took off for Rome, by a TMZ paparazzo on a Los Angeles sidewalk, and he’d answered that he had no idea. The only time, he said, he was sure it would get made was when “David Chase runs out of money.”

Even that won’t be enough to get it made now, because there is no

Sopranos

without Tony Soprano. James Gandolfini’s creation, from 1999–2007, of the lugubrious mob boss with such mother problems that he starts seeing a female therapist, became one of the most indelibly mythic characters of American television. Tony was a kind of cross between Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski and Carroll O’Connor’s Archie Bunker, a raging id of greed and lust who could make you laugh at the clumsiness of his surgically precise malapropisms. Tony was “with that Senator Sanitorium” on the issue of gay rights; he could be “prostate with grief”; revenge, he believed, was “like serving cold cuts.”

And yet, Tony was not a buffoon. Or anyway, not just a buffoon. Something in the alchemy of Gandolfini’s performance made Tony very real to millions of Americans and fans around the world. So real that James Gandolfini’s death seemed as if it had happened to a neighbor, or a relative. His death was all in the family.

And at the same time, it was

Six Feet Under, Deadwood, The Shield, Mad Men, The Wire, Breaking Bad,

and

Justified.

James Gandolfini was one of those actors who changed the medium in which they performed. It’s often said that he introduced an era of TV antiheroes. What he definitely did was show us a bad man who hurt other people out of his own vulnerabilities. As America went around serving cold cuts to the rest of the world after 9/11 (the Twin Towers fell within sight of some of the scenes in

The Sopranos’

famous opening credits), and its rusting middle-class economy barreled toward decline and collapse, that theme seemed to take on an importance far beyond TV itself.

* * *

To understand James Gandolfini, it’s important to know that all roads lead to Rome—but they start in New Jersey. Where your birthplace can be an exit ramp.

“A large number of actors and musicians are from [New Jersey],” Gandolfini once told

The New York Times

. “We are overrepresented in the culture. You have a blue-collar, middle-class sensibility right next to one of the greatest cities in the world, which can make for some interesting creative impulses.”

Like, maybe, the impulse to take a baseball bat to polite culture, or the impulse to grab pleasure hard, or just the impulse to give in to your impulses. People forget, but it’s no accident that Roy Lichtenstein invented Pop Art while he was teaching at Rutgers, or that Bruce Springsteen was mourning the death of the American Dream before the media across the river realized it was sick. The state’s greatest poet, William Carlos Williams, was an obstetrician serving poor, immigrant, working-class families in Paterson from a horse and buggy.