Jacquards' Web (20 page)

Authors: James Essinger

Evermost truly yours

C. Babbage

This is a very similar salutation to one he uses just three days later in a shorter letter he writes to Ada from Dorset Street. He concludes this one with the phrase:

Ever my fair Interpretress.

137

Jacquard’s Web

Babbage, it seems clear, while in no way seeing Ada as a partner—even a junior partner—in his intellectual labours, did regard her as someone who was interpreting his work for a wider audience. This seems to tally pretty accurately with what is revealed by circumstantial evidence about the nature of their collaboration and by the different nature of their writing.

Once we reach the conclusion that the discursive and emotional element of the Notes was indeed Ada’s, we can fully appreciate one particularly important aspect of the Notes: her brilliant and inspired appreciation of the crucial conceptual links between the Jacquard loom and the Analytical Engine.

Ada’s Notes provide abundant evidence that Babbage’s adoption of the Jacquard loom control system was the aspect of the Analytical Engine that interested her most of all. Indeed, it seems very likely that it may have sparked her fascination with Babbage’s most ambitious calculating Engine.

We must remember that Ada and her mother were both

aware of the Jacquard loom and the punched-card system it employed

before

Babbage himself had the idea of employing the Jacquard cards in his Analytical Engine. In the summer of

1834

, six months before the December evening when Babbage revealed his intellectual breakthrough to his three guests, Ada and her mother toured the industrial heartland of northern England.

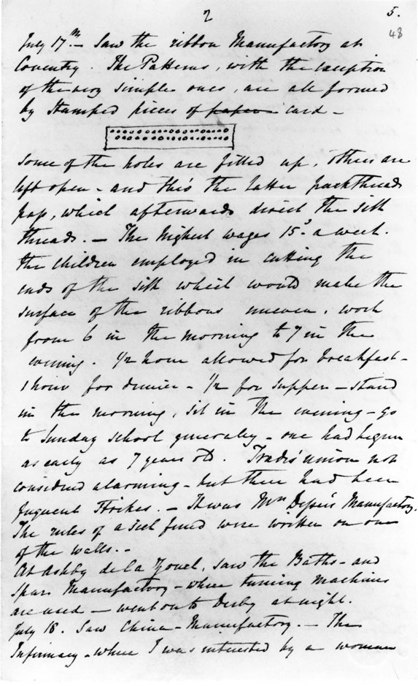

They saw various looms in action, and Lady Byron drew a picture of a punched card used in weaving ribbons.

The idea of the Analytical Engine as a kind of Jacquard loom that wove calculations had a deep and enduring appeal for Ada.

When we look carefully at Babbage’s writing style compared with Ada’s, we are driven to the conclusion that he saw the world, and mechanisms, in a much more literal, factual, and indeed

analytical

way than she did. For Ada, inventing metaphors for understanding science was second nature. Babbage hardly ever did this.

(

right

) Lady Byron’s sketch of a punched card used in ribbon manufacture.

139

Jacquard’s Web

But the real point—and this explains why Ada’s contribution to the idea of the Analytical Engine is so important—is that

the

brilliance of the conception of the Analytical Engine requires both a

scientific and emotive perception if it is to be fully understood and

expressed

.

This, in fact, tallies neatly with an intriguing point Ada herself makes in a letter to Babbage at around this time, when she insists that her friendship with Babbage should be founded on

‘imaginative roots’ as well as on the more fundamental scientific aspects of their collaboration.

In the letter, dated

5

July

1843

, Ada quotes a question Babbage had evidently asked her in a letter she received from him, and which has presumably been lost, for no letter from Babbage to Ada containing such a question survives in the extant correspondence. She goes on to make an important statement about the difference between how she thinks and how Babbage does.

‘Why does my friend prefer

imaginary

roots for our friendship?’—Just because she happens to have some of that very imagination which

you

would deny her to possess, & therefore she enjoys a little

play & scope

for it now & then.

Ada sometimes made extravagant and unjustified claims about her scientific and mathematical understanding, but no one who reads her letters or the Notes could deny the quality of her imagination.

The entire metaphor Ada uses throughout the Notes to describe how the Analytical Engine works is founded in the operation of the Jacquard loom. Her writing makes the link between the Jacquard loom and the Analytical Engine about as explicit as it could possibly be. As she says:

The distinctive characteristic of the Analytical Engine, and that which has rendered it possible to endow mechanism with such extensive faculties as bid fair to make this engine the executive right-hand of abstract algebra, is the introduction 140

The lady who loved the Jacquard loom

into it of the principle which Jacquard devised for regulating, by means of punched cards, the most complicated patterns in the fabrication of brocaded stuffs. It is in this that the distinction between the two engines lies. Nothing of the sort exists in the Difference Engine. We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine

weaves algebraical patterns

just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves. [Ada’s italics.]

This last sentence summarizes with great precision, and a really delightful clarity and expressiveness of language, the entire nature of the connection between Babbage’s work and Jacquard’s loom. Ada often pursues this connection elsewhere in the Notes.

Her Note F, for example, starts with a mention of ‘a beautiful woven portrait of Jacquard, in the fabrication of which

24 000

cards were required’. This, of course, is the woven portrait which so fascinated Babbage and to which he was so devoted.

One can easily imagine that Babbage and Ada were utterly intrigued by the woven portrait of Jacquard. How one yearns for some record of their conversations about it!

And now look at how, in Note A, Ada pays particular attention to the importance of the Jacquard loom control system in the operation of the Analytical Engine.

In … what we may call the neutral or zero state of the engine, it is ready to receive at any moment, by means of cards constituting a portion of its mechanism (and applied on the principle of those used in the Jacquard-loom), the impress of whatever special function we may desire to develop or to tabulate.

Ada proceeds to define the purpose and use of the cards in precise terms. What she says about these cards is exactly what could be said about modern computer software.

These cards contain within themselves the law of development of the particular function that may be under consideration, and they compel the mechanism to act accordingly in a certain corresponding order.

141

Jacquard’s Web

Elaborating in the same Note on the distinction between the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine and on why the Analytical Engine represents such a revolutionary breakthrough, she observes:

The former engine [i.e. the Difference Engine] is in its nature strictly

arithmetical

, and the results it can arrive at lie within a very clearly defined and restricted range, while there is no finite line of demarcation which limits the powers of the Analytical Engine. These powers are coextensive with our knowledge of the laws of analysis itself, and need be bounded only by our acquaintance with the latter. Indeed we may consider the engine as the

material and mechanical representative

of analysis, and that our actual working powers in this department of human study will be enabled more effectually than heretofore to keep pace with our theoretical knowledge of its principles and laws, through the complete control which the engine gives us over the

executive manipulation

of algebraic and numerical symbols. [Ada’s italics.]

The following passage, which enlarges on the role of Jacquard’s cards in the Analytical Engine’s operation, is another typical example of the clarity and focus of Ada’s own thoughts on the Analytical Engine.

The bounds of

arithmetic

were however outstepped the moment the idea of applying the cards had occurred; and the Analytical Engine does not occupy common ground with mere

‘calculating machines.’ It holds a position wholly its own; and the considerations it suggests are most interesting in their nature. In enabling mechanism to combine together

general

symbols, in successions of unlimited variety and extent, a uniting link is established between the operations of matter and the abstract mental processes of the

most abstract

branch of mathematical science. [Ada’s italics.]

And Ada concludes:

142

The lady who loved the Jacquard loom

A new, a vast, and a powerful language is developed for the future use of analysis, in which to wield its truths so that these may become of more speedy and accurate practical application for the purposes of mankind than the means hitherto in our possession have rendered possible. Thus not only the mental and the material, but the theoretical and the practical in the mathematical world, are brought into more intimate and effective connection with each other

.

We are not aware of it being on record that anything partaking in the nature of what is so well designated the Analytical Engine has been hitherto proposed, or even thought of, as a practical possibility any more than the idea of a thinking or of a reasoning machine.

If this is not a stunning and brilliant anticipation of the computer revolution that was to take place more than a century later, what is?

Ada was profoundly excited by her work on the Notes. On Sunday morning,

2

July

1843

, while she was still working on the Notes, she wrote Babbage a letter from her country home at Ockham, Surrey. The letter contained the following intriguing paragraph:

I am reflecting much on the work & duties for you and the engine, which are to occupy me during the next two or three years I suppose; & have some excellent ideas on the subject.

The letter suggests that Ada regarded her work on Menabrea’s paper, and the Notes she produced, as just the first stage of her new career as Babbage’s interpreter. But in the absence of any other worthy papers on his work being published in a foreign language with which she was familiar, what else did she think she could do for him?

The answer would come in another letter—the longest she ever sent Babbage. She wrote it on Monday,

14

August

1843

.

Covering sixteen pages of her close handwriting and more than

2000

words long (the full text of this fascinating letter is 143

Jacquard’s Web

contained in Appendix

2

to this book), the letter constituted nothing more or less than an offer to handle, from henceforth, what would be regarded today as the people management, political, and public relations aspects of Babbage’s work on the Analytical Engine. Ada admired Babbage enormously but she was certain that the pedantic and undiplomatic aspects of his personality handicapped him when it came to advancing the cause of his Engines. She was perceptive enough to understand something Babbage never understood: that advancing his project required not only technical wizardry but also a profound skill at dealing with influential and sceptical people.

As Ada wrote in the letter:

I want to know whether if I continue to work

on

&

about

your own great subject, you will undertake to abide wholly by the judgement of myself (or of any persons whom you may

now

please to name as referees, whenever we may differ), on

all

practical

matters relating to

whatever can involve relations with

any fellow-creature or fellow-creatures.

But Ada never got the opportunity she craved.

At the top of the long letter that Ada sent him on

14

August and which is to be found in the Babbage papers, there appears a pencilled note in Babbage’s handwriting that states: Tuesday

15

saw AAL this morning and refused all the conditions.

Babbage’s own note really is as abrupt and dismissive as that.

Babbage could, sadly, on occasion be selfish, stubborn, and ungenerous of spirit where his work was concerned. In that short note he combines all three vices. Despite his respect for Ada’s ability to articulate and popularize the most important project of his life, he could never see her as anything more than an ‘interpreter’.

Ada’s reaction to his decision is not recorded, but I believe she would have been enormously disappointed by what was a 144

The lady who loved the Jacquard loom

silly and arrogant decision on Babbage’s part. She would still have required his guidance and on occasion he would have had to check her youthful impetuosity, but if she had thrown her energy behind his project in the way she wished, who could tell what success the Analytical Engine project might have achieved?

Ada’s translation of Menabrea’s paper on the Analytical Engine was published in September

1843

in the third number of

Scientific Memoirs

. Entitled

Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by

Charles Babbage, Esq. (by L. F. Menabrea, with notes by Ada Lovelace)

, it was respectfully received by the scientific and mathematical community. But it did not cause the sensation Babbage no doubt hoped for, nor did it prove to be the springboard to a literary and scientific career for Ada. Yet the translation and Notes furnish a beguiling description of a nineteenth-century cogwheel computer. It is a pity that so few people had the prescience to notice its importance at the time. Posterity, however, has viewed Ada’s work in an infinitely more significant light.