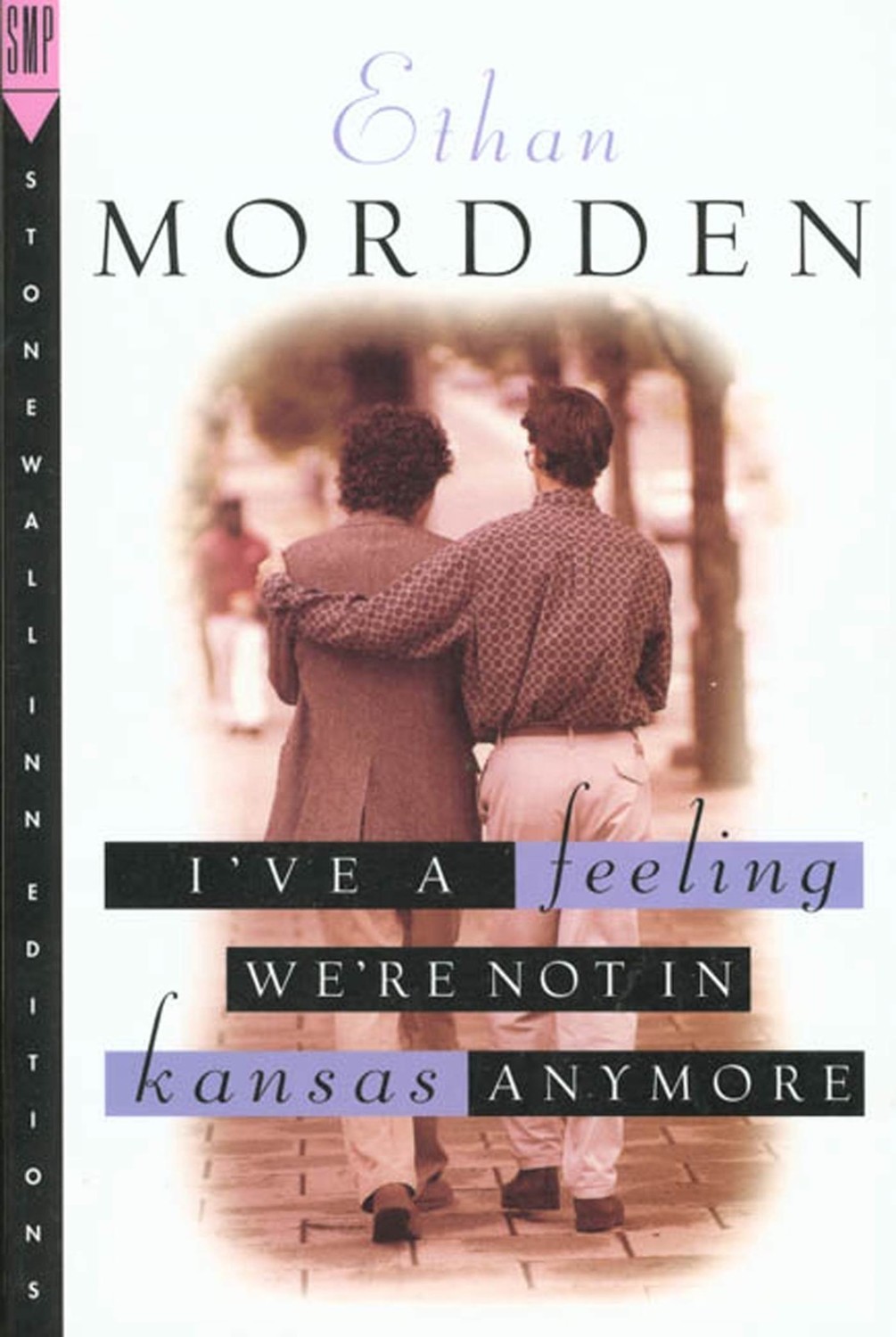

I've a Feeling We're Not in Kansas Anymore

Read I've a Feeling We're Not in Kansas Anymore Online

Authors: Ethan Mordden

Tags: #Fiction, #Gay, #Romance

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

The Straight; or, Field Expedients

The Precarious Ontology of the Buddy System

The Shredding of Peter Hawkins

The Disappearance of Roger Ryder

To Michael Denneny,

sine qua non

The author wishes to acknowledge the strategic collaboration of the house team, which, he is glad to note, still includes the masterful Ina Shapiro, one of the most precise of stylists. Paul Liepa keeps a yare ship, Deborah Daly is indispensable in jacket-art meetings, Izume Inoue presents a unique rendering of The Emerald City of Manhattan on the cover, Laura Hough designed what IBM would call a “reader-friendly” book, Carol Shookhoff assisted in the typing of a printer-friendly manuscript, and, for the home side, there remains the redoubtable Dorothy Pittman, the author’s best friend and agent, in that order. As for Michael Denneny, the editor of this book, I have expressed my feelings a few pages to the fore.

In particular, I would like to thank Charles Ortleb, the founder and publisher of

Christopher Street,

where a substantial share of post-Stonewall gay lit has originated—not because writers have battered their way in, but because Chuck personally stimulated, encouraged, and in some cases helped subsidize their careers. Without his insistence that gays maintain at least one forum for new journalists, storytellers, and poets, gay publishing might have consisted of nothing but an occasional shuddering of the linotype’s chromosomes.

I have sat with friends—and I mean very close friends—on those long nights at the Pines, listening to the ocean dancing about our mysterious island, and on those long days at the brunch table, trying to remember to be urbane, and on those odd, ironic afternoons of confessing feelings of such intimate enthusiasm or disappointment that one regrets having made them for the rest of one’s life. We have traded tales, my buddies and I: of affairs, encounters, discoveries, weekends, parties, secrets, fears, self-promotions—of fantasies that we make real in the telling.

Well, it occurs to me that all of gay life is stories—that all these stories are about love somehow or other, and that many jests are made in them, though the overall feeling may be sad. One’s life breaks into episodes, chapters of a picaresque adventure. As each episode ends, the material for the next shifts into place. Defunct characters cede to new ones, though a few figures—the best friends—hold their places throughout. A happy ending must be temporary, and a gloomy one may yield to surprising amusement without warning. It is a lively life I sing, with but two constants: humor and friendship. I am looking back now on what I have seen and heard, and on the men I have known, and on certain perceptions I am reluctantly compelled to share. And these are my tales …

At night, writing longhand in a spiral notebook at my desk, I can see my reflection in a window washed in lamplight, as if I were working before a mirror. I have a romance going that I am my characters, and can put on any of their faces at will. I can be all forearm and fist, or startled behind spectacles; I can wear my college sweatshirt, or hold my pen in an old-fashioned manner. When I view my reflection in the window, I am telling stories.

I say this because I recall that the drag queen recounted her saga into a great mirror that stood just over my left shoulder. She scarcely looked at me, or at her friend Paul, who had brought me to her.

“You must tell her story,” Paul had urged. “This is gay history.”

No, I was writing nonfiction then. I had no reflection. “I wouldn’t know where to sell it,” I told him. No stories.

“Try,” he said. “Just take it down.

Someday.

”

I was intrigued. Paul arranged it, took me to a shabby walkup where Bleecker Street meets The Bowery, introduced us, and—breaking his word of honor not to leave me alone—walked out. “You’ll see,” he murmured. “See what?” I answered; he was already at the door, waving.

“‘Who was that masked man?’” I quoted, to cover my embarrassment. And: “Why does everyone I know run out on me after five minutes?”

This was eleven years ago. The drag queen was perhaps fifty. Black cocktail dress, spike heels, cabaret mascara, and opera jewelry.

“When Miss Titania gave an order, you obeyed or that’s it, you were out! You were glue. You were

grovel!

I mean. Miss Titania was the very certain queen of the Heat Rack—and was she big, I ask you? Bigger than a Zulu’s dingus on Thursday night. Big in

spirit!

Miss Titania had her court, and everyone else was dogmeat when Miss Titania got through. Ask anyone. I don’t know where they are now, but you ask them.”

My pen flew. “Where’s Miss Titania now?” I asked.

The drag queen shrugged. “It’s all gone, so that is no question at all to me. Now every man in the city looks like trade in those muscle shirts, with those demure little bags like they’re carrying their makeup kit or I don’t know what. I don’t think there’s a man in New York who isn’t available. Once even the gays were straight; now all the straights are gay. New York doesn’t like queens anymore, regardless. We’re the old revolutionaries. They say we dressed up because we were flops as men. Born to be freaks. They say we didn’t care what other folks thought.” She lit a cigarette like a woman, blowing the match out; and held it like a man, between thumb and forefinger. “Well, it’s not true. We dressed up so they could see how lovely we are. We hope they see it.”

“What if they don’t?”

“Then we say something pungent.”

“Tell me about Miss Titania.”

“She was ruthless. The Heat Rack was her court, and

no one

upstaged her. The dire episodes! Once an upstart southern belle came in out of nowhere—I suspect Scranton—and there she was, taking up space and flouting Miss Titania. I will never forget—‘Mr. Sandman’ was playing on the juke, and Miss Titania liked to sing along, you know, such as ‘Mr. Sandman, please make me cream.’ A slightly altered version of the original, as I recall. Well, La Southern Comfort cries out, ‘Deyah me, it would surely take the entiyah football teyum? at Ole Miss? to make you-all creayum, I’m shuah?’ And there was such silence in the whole place. Except for ‘Mr. Sandman.’ I

mean.

Even the toughest trade shut up. And Miss Titania. She looks at that no-good, lightweight daredevil, and smiles her famous smile and puts down her drink and fan. And suddenly, I don’t know, it couldn’t have been more than a few seconds, but Miss Titania flies across the room and rips the hair right off that southern girl’s head—I mean her wig, truly; did you think I meant her skull hair? because, really, what an odd look you’re wearing—and then Miss Titania rends the bodice of the southern girl’s gown and pulls off her pathetic training bra or whatever she had on, and we are all roaring with laughter, so that southern girl runs into the ladies’ and won’t come out till the place is closed. We never saw her after that. Because you

don’t

challenge the queen in her own court.

“And Miss Titania was the absolute queen. Even the Duchess of Diva, who presided over Carney’s on Thirty-eighth Street—even she knew better than to tangle with Miss Titania. And the Duchess was a gigantic mother. She must have weighed three hundred pounds. Always wore black, for her husband. He died in the war. And did she have a savage streak. Everyone feared her. But Miss Titania had the prestige.”

“Tell me more about the Heat Rack.”

“Or the Pleasure Bar, or Folly’s, or The Demitasse, or Club La Bohème, or sometimes no name at all. It changed by the week. To me it was always the Heat Rack, because that’s what they called it when I made my choice.”

“Your choice?”

“Between love and beauty. Surely you know that every queen must choose between living for the one or the other. You can’t have both.” She rose and presented herself to the mirror pensively. “I chose beauty, because I imagined that those who know about love can never have it. Do you think so, too?”

I was young then, and never thought about it. Now, in my window, I wonder. The woman across the way, in direct line of my desk, becomes unnerved at my concentration, and lowers her blinds.

“The bars today are just saloons,” the drag queen goes on. “The Heat Rack was our fortress and fraternity, the only place where

we

made the rules. We rated the beauty and arranged the love stories.” She sweeps through the dismal room, touching things. “The whole world is just queens, johns, trade, and cops. The whole world. And Miss Titania kept them

all

in line. Yes. Yes. Yes. And she was kind and beautiful.”

She is not speaking to me.

“The johns you respect. The trade you screw. The cops you ignore. Life is so simple in the Heat Rack. Now I’ll tell you the difference between queens and trade.”

She is looking hard at me for the first time.

“Queens are afraid that every horrible insult hurled at them is true. Trade is impervious to insult.”

I take notes.

“That’s why these Stonewall men all look like cowboys. They think if they play trade they won’t have their feelings hurt. I would imagine that is why you’ve got dark glasses on right now.”

“I always have dark glasses on.”

“That’s fascinating, no doubt. But how nice of you to wear a tie for me, all the same. The johns always wore ties.”

In my window, it’s always T-shirts. Once I came home from the opera so keen to write I sat down in my suit. Then I looked up and thought, “Who is that man?”

“The johns were so nice. All those years at the Heat Rack, never did I have to buy my own drink. Of course, they were living for love, so they were always getting wounded.”

“What does trade live for?”

“To torment queens. That’s why Miss Titania had to enforce the regulations so strictly, to keep trade from cheating the johns and breaking their hearts. Or making a ruckus, which they always did. Or showing off their stupid tattoos with a lady present. And some of them never washed and you could smell their asses all the way across the room. Now, the Duchess of Diva, she let trade run

rampant

in her court. Mind you, I’m for a free market. But you give trade their liberty and what do you have?”

“Tell me.”

“A world in which beauty passes the laws and all lovers go mad. I’m sure you know this, a writer. Do you write poems?”

“Never.”

“I yearn for poetry. But no one rhymes anymore. No one lives for beauty. Everything is …

meaning.

There’s always a message now. What’s the good in a message when a pretty picture tells you everything you need to know?

“Now, I can tell you, on some nights the Heat Rack was the prettiest picture you ever hoped to see. In summer, let me say. The johns in the dark corners or sitting in the back booths, out of the way. And trade all around, some shirtless and so still, not looking to see who saw them. Three or four, perhaps, loafing at the pool table—not even playing, I expect, just filling out the tableau, making silly jokes and rubbing each other’s necks and getting pensive. And the queens were near, doting. You would look for a moment at all this, all around, and it was like a painting. It was magic, regardless.