It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (6 page)

Read It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War Online

Authors: Lynsey Addario

Sometime around my twenty-fifth birthday, the last of my three sisters got married, and I had an epiphany. My father and Bruce had given each of my sisters $15,000 to spend toward their wedding costs. Miguel and I had broken up when we moved back to New York, and I knew I would never get married in my twenties; in fact, I wasn’t sure I would ever love anything as much as photography. So I made my father and Bruce a proposition: “If you advance me my wedding money now, I can use it to invest in my career, and I will one day have enough money to fund my own wedding.” They agreed. I bought new cameras and lenses and put the rest of the money in the bank.

• • •

A

FTER LESS THAN A YEAR

back in New York, I was desperate to travel and looked to Latin America once again. One country intrigued me most, perhaps because it was off-limits: Cuba. In 1997, Communist Cuba was embargoed, and Americans rarely visited. Being a foreign journalist in Cuba was also risky; the government monitored foreigners they suspected would publish negative stories about the ailing Communist system. I didn’t know anyone who had been there; at the time I didn’t know one foreign correspondent and knew few other journalists. But I was bursting with curiosity and the daring of youth. I was fascinated by the steady rise of capitalism in such a steadfastly Communist country.

Cuban couple watching Fidel Castro on TV at home, 1997.

I landed in Havana in May. As I rode the minivan from the airport into the city, I looked down at my nervous hands holding a sheet of paper with fading blue lines and the address of my destination and realized I was very alone. I read the address to the bus driver in rusty Argentine Spanish and felt an instant attachment to him. I wanted to spend the rest of my trip on the bus. Through the window I saw that Havana was decrepit. Some buildings had paint peeling away from their facades; others were just a heap of exposed, rotting wood. Rooftops had lost shingles; clothes were hanging up to dry in the pouring rain; boys nonchalantly rode their bikes through twelve-inch puddles. When I got out at my stop, two women and a man looked at me as if I carried a banner that said

AMERICAN CAPITALISM

. I was a stranger: My shoes were too new and well made for me to be Cuban. Even my hair clip would cost a month’s wages there.

In a travel book I had found an agency that arranged home stays, and they placed me with a woman named Leo, whom I paid $22 a night for a small room. She greeted me as if I were an old friend. On my dresser she left two tiny bars of soap stolen from an American hotel in the mid-1970s. She left chocolates next to the soap. They were stolen from the same hotel.

Three rocking chairs awaited on the glassed-in terrace with a ninth-story view, and Leo and her mother, Graciela, took their places and motioned me to sit. We began exchanging the usual questions, small talk, one-word inferences, and waited for intonations that quickly became familiar. We rocked in our chairs, and everything I had read about the situation in Cuba—the failures of communism, the poverty, the hardships, the lines for food, the struggle for basic amenities, the disparity between those who paid in dollars and those who paid in meager pesos—was confirmed by Leo and Graciela in the span of hours. Our conversation carried on from early evening into the night, and we lingered comfortably with the Cuban breezes blowing in and out of the patio windows. I had expected Cuba to be this ominous, scary dungeon, but the people were so warm, so candid—just like anyone else.

Several days after I arrived, I finally went to Publicitur, the organization that represented Cuba’s International Press Center and provided minders for foreign journalists. Minders were government-appointed guides who accompanied journalists around, wrote up reports detailing every person the journalists interviewed and every place they visited, and then passed this information on to the government. I introduced myself to the secretary at the front desk. They recognized me as “the American journalist”; they were expecting me. The secretary led me to a room where two young women who prided themselves on their textbook English and secondhand knowledge of the outside world were seated at a table. The directors of Publicitur who oversaw the minders were eager to answer a list of questions I had prepared about Cuba and its mechanisms and to arrange my requests to photograph in certain places. I could tell instinctively I would never get the information I wanted from them. They claimed they would arrange shoots for me inside government buildings and hospitals, but I knew that in a country like Cuba they would not. It was my first experience in a country that provided government minders to journalists and blatantly restricted my movements.

While all who worked at Publicitur and the International Press Center were eager to show me Cuba’s touristy sights—Varadero Beach, the Tropicana, the recently restored Old Havana area—they were equally eager to keep me away from the run-down neighborhoods.

It was the rainy season, and the streets were hard to photograph. I walked the city from end to end, for hours and hours each day, in search of images, drenched from the humidity, exhausted from the heat, and sick of hearing the flirtatious

“ssssst”

from men surprised to see a foreigner. I walked so much and spent so much time looking for the right light or the right angle of a shiny old American car in front of a decaying building that even my minders got bored with me and decided I wasn’t worth following around. For a few days, there wasn’t enough water for bathing, and soon I smelled from my long days of walking. I thought I might collapse from the heat. But as I roamed around the Cuban villages alone, camera in hand, I also felt satiated, at peace. I felt at home.

As soon as I returned to New York after a month in Cuba, I thought only about getting back on a plane. I didn’t want to lose the momentum of travel and discovery or sink into the trap of a comfortable life. But I trudged through two more years of paying my dues in New York, visiting Cuba again in 1998 and 1999 to satisfy my wanderlust.

In 1999 Bebeto came to me with an idea. In the past year there had been a series of murders in the transgender-prostitute community in New York. Rather than order an investigation into the crimes, the AP had heard that Mayor Giuliani had decided the community wasn’t worth the city’s resources. An AP reporter wanted to explore the idea that transgender prostitutes were society’s throwaways. It was my first long-term assignment, my first opportunity for a real photo-essay.

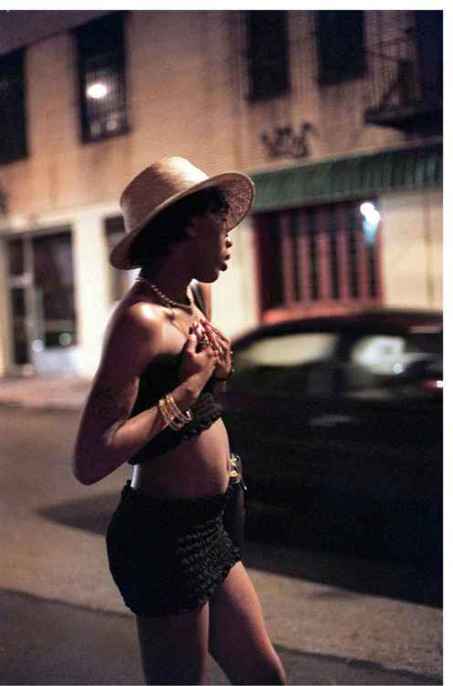

Transgender prostitutes in the Meatpacking District in New York, 1999.

In the beginning, the reporter and I ventured out together in the Meatpacking District to make inroads into the seemingly impenetrable world of transgender prostitutes. We traveled with a local organization that distributed condoms and information on sexually transmitted diseases on the neighborhood’s busiest weekend nights. I never took out my camera. Once we made some initial contacts as a team, I decided to venture out on my own, and for weeks I went out almost every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday night—often without my cameras—and hung around the Meatpacking District like a groupie, trying to gain the women’s trust. I was the only white girl among a tribe of Latinas, blacks, and Asians, and they were skeptical of my intentions. Finally a woman named Kima, who walked the then desolate streets in front of what is now the fashionable Pastis restaurant, invited me to her apartment in the Bronx projects. “Be there around midnight. You can hang out with us and then come downtown to work with us.” I asked if I could bring my cameras. She agreed.

I showed up at Kima’s with chocolate-chip cookies and milk. I’m not sure what I was thinking, bringing chocolate-chip cookies and milk to an apartment full of transgender prostitutes who lived on drugs, alcohol, and fast food—but I didn’t want to arrive empty-handed, and I didn’t think it was ethical to bring booze. (I later learned otherwise.) A handful of women were there, injecting themselves with black-market hormones, drinking, dancing, getting made up. They let me shoot whatever I wanted. For five months I spent almost every weekend with Kima, Lala, Angel, and Josie. As I gained their trust, my photographs became more intimate; time allowed me to see things I hadn’t before, like when a tough guy who looked as though he had strutted out of a Snoop Dogg video would gently comb his transgender girlfriend’s hair in the dim light of a street lamp while she waited for her early morning clients.

One night I went on my first date in months, with a musician who played the saxophone in a Cuban band. Around 1 a.m. he walked me home along Christopher Street to the corner of West Tenth Street. We looked down at our feet and kicked our heels around in circles as we made meaningless conversation. Finally he kissed me.

Minutes had gone by when I sensed a group of people too close to us. I opened my eyes and saw shadows dancing around our feet.

“IT’S THE PHOTO LADY!”

It was Kima and Lala and Charisse and Angel—an entire posse of the trannies. They screamed and laughed, and they got closer and closer to me and the poor musician.

“Woohoo, you go, girl!”

The musician was confused: “What did you say you did for a living again?”