It's Not Luck (11 page)

Authors: Eliyahu M. Goldratt

I don’t answer.

“Take your group as an example. We invested almost three hundred million dollars in it. What we’ve gotten back so far is zilch. And now we will be lucky if we can sell it for half. Who’s money is it, do you think? Who paid for it?”

“My group is not losing money anymore,” I say. “Give me some more time and I will make it really profitable. Why sell now?”

“Alex, how profitable can you make the diversified group? I’ve seen your forecast for this year. Do you realize inflation exists? In order to protect the value of the money, and bearing in mind how risky it is, we must invest only in companies that have a real chance of making more than inflation.”

I see where he is coming from. I cannot guarantee that my companies will bring more than inflation. Still . . .

“That’s the most unpleasant part of my work,” he continues. “Sometimes management makes a bad decision; it is unavoidable. But when they insist on protecting their bad decision, we have to step in. That’s our job. Remember, the goal is to make money. Your companies have to go Alex, it is unavoidable.”

Trumann doesn’t have to tell me that the goal of my company is to make money. That has been my motto since I became a plant manager. But at the same time, I was careful not to do it at the expense of my people. I never thought that the way to make more money was through slashing parts of the organization. That is Hilton Smyth’s way. To save some pennies he will cut anyone.

“I don’t think that in my case,” I try to choose my words carefully, “it’s a matter of protecting a bad decision. I have nothing to protect. I wasn’t involved in making the decision to diversify. Still, I’m not sure that it is correct to sell my companies.”

“Why?”

“Because we are not dealing only with money. We are also dealing with people. Top executives, I think, have responsibility not only to our shareholders, but also to our employees.”

Maybe I just signed my death sentence, but what the heck, there is a limit to the extent I’m willing to play their money game. Let me give it to him in full. “Sometimes, from where I stand, it seems unfair to put the squeeze on the employees, who have invested their lives in the company, just so that some rich people will become even richer. . . . The goal of our company is make more money, but that’s not the whole story.”

Trumann doesn’t seem surprised. He has heard such things before, even though I wonder if he has heard it from one of his executives. Maybe from an ex-executive.

“Some rich people become even richer.” He repeats my words. “Alex, where do you think the money that I invest comes from? Rich investors? Banks? Don’t you know that most of the money invested in the market belongs to pension funds?”

I feel myself blush. Of course I know it.

“People save all their lives for old age.” Trumann explains the obvious to me. “They are saving now so that in twenty or thirty years they can retire peacefully. It is our job to make sure that when they retire the money will be there for them. Not dollar for dollar, but buying power for buying power. It’s not the rich peoples’ interest we are watching out for, it is the same people you are worried about—the employees.”

“Interesting cloud,” I totally agree.

Trumann looks disappointed. “Don’t dismiss what I’m saying. I’m not talking about clouds, I’m talking about facts of life.”

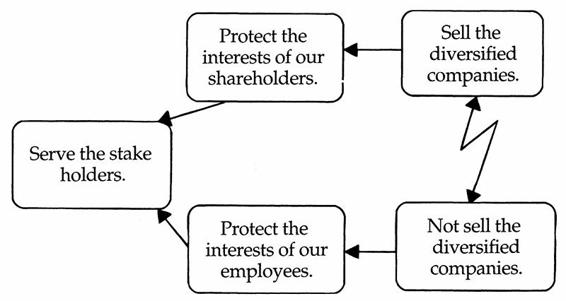

Rather than trying to explain, I take out my pen and start to draw the cloud. “The objective is to serve the stakeholders. Do you have any problem with that?”

“No. I only have problems with people who forget it.”

“To achieve it, we must make sure to satisfy two different necessary conditions. One is to protect the interests of our shareholders, and the other is to protect the interests of our employees.” I wait for him to object, but he nods his head in agreement.

“In order to protect the interest of our shareholders, you insist on selling the diversified companies.”

“Don’t you agree?” he asks.

“I agree that under the current circumstances, to protect the interests of the shareholders we should sell the companies. But that doesn’t mean that I agree we should sell them.”

“Alex, you sound like a politician. Do you agree or don’t you?”

“There is another side to this question; bear with me. We also said that we must protect the interests of our employees. But in order to do that we must not sell the companies.”

I am expecting that he will not agree, that he will claim that selling the companies has nothing to do with the interests of the employees. But he doesn’t say a word. He takes the napkin and examines the cloud.

“You have it easy,” I say. “To you it’s obvious that we should sell the diversified group. You look at the bottom line numbers, you look at the forecast, and they tell you the answer. Not enough money now as well as in the future—sell. No wonder, you look only at one side of the equation, as you should. That’s okay, it’s compensated for by the employees and the unions who also look at only one side. Only we, the executives, are torn. We are in the middle. We have to satisfy both sides. Put yourself in my shoes and try to answer your question, to sell or not to sell the companies. You see, it’s not so easy to answer.”

Still looking at the cloud he says, “We do look at both sides of the equation. Maybe we didn’t do it in the past, but now we definitely do. No prudent investor is investing by just looking at the numbers. We learned, the hard way, that the key factor is the people. If they are not pleased with their jobs, if they are not proud of their company, it’s just a matter of time until losses will start to show up.”

“I guess that the same is true for the unions. They know that there is no job security in a company that loses money, no matter what we, the executives, promise them. More and more they start to demand to see our investment plan before they’ll even consider giving any concession.”

He raises his eyes from the cloud and looks at me. “In our case I think that it is.”

“What is?”

“I think it is easy to answer that we should sell your companies. No, don’t get excited, let me finish. Look, you know our credit rating. You know that it’s almost at rock bottom.”

I know. We pay two percent above prime.

“Everybody is trying to cheer me up by the market upturn. But markets oscillate, the downturn will follow. The last downturn almost brought UniCo to its knees. We don’t have the reserves anymore to carry us through another down period, and I don’t think that we can count on gathering enough reserves in the current good period. Nobody knows how long it will last, and everybody is telling me that it won’t be easy to make money in this upturn, that pressure to reduce prices continues.”

I start to see his point.

“Alex, even if I forget my bosses for a minute, even if I concentrate on the interests of the employees of UniCo, I come to the same conclusion: we must sell some portion in order to protect the others. And the diversified group is the only choice; we have to protect the core business.”

“But why by selling it now? Why not accumulate profits as long as the market is good?”

“The timing has very little to do with Granby’s retirement,” Trumann answers my unspoken concerns. “It is the time that we can probably get the best price, when everybody is looking hopefully into the future.”

“We bought my companies under similar circumstances, in 1989 when everybody was expecting an upturn. And we definitely paid exaggerated prices.”

“Exactly my point,” he sighs.

“This is interesting,” he says after a while. “Where did you learn this presentation technique?”

“It is neat. On half a page you see the entire picture.”

“Right. The conflict hits you right between the eyes. You can’t ignore the real issue. It’s a powerful way to present.”

“It’s not just a presentation technique,” I comment. “This technique claims that you should not attempt to strive for a compromise. It advocates examining the assumptions under the arrows in order to break the conflict.”

“What do you mean?”

Jonah claims that any cloud can be broken, but he is wrong. If I could find a way to break this conflict, I wouldn’t have to sell my companies. Now, because of my big mouth, I have to defend his technique.

“Look, for example, at this arrow,” I say to Trumann. “ ‘In order to protect the interest of the shareholders, we must sell the companies.’ The assumption here is that the companies are not profitable enough. If we can find a way to make them more profitable, a way that will guarantee that they can sell many more products without increasing their operating expense, then the cloud is broken. We don’t have to sell the companies. We simultaneously protect the interests of the shareholders and the employees alike.”

“Do you know how to do it? Do you have an idea how to increase their product sales without increasing their operating expense?”

“No,” I admit. “I don’t see any way to do it.”

He smiles. “So even though in theory the conflict can be eliminated, in practice we have to live with it. I guess that there is quite a distance between nice theories and harsh realities.”

I must agree with him.

At first sight the cabs in London look strange, but when you enter one, it looks even stranger. In the back there is one seat, big enough for only two people. Two more shelves for sitting can be folded down from the wall separating the driver from the passengers. Even in a train I hate to sit with my back to the driving direction. In a cab, facing Trumann and Doughty, I like it even less.

We are returning from a meeting where we negotiated the sale of Pete’s company. Actually, this is not an accurate description. We didn’t negotiate anything, we just talked—mainly me. Four people asked questions, and because of the nature of the questions, Trumann and Doughty let me answer. Most of the questions honed in on the reasons for the exceptional operational performance (not to be confused with exceptional financial performance, of which Pete’s company is innocent).

It took me quite a while to explain how come on-time delivery is so high, while inventories are so low. It’s not easy to explain to people whose starting point is so different. People who think that managers must concentrate on squeezing the maximum from each link, when by doing so they unintentionally jeopardize the performance of the chain. I had to prove why efforts such as trying to save set-up on the presses, or optimizing the work load of each technician in the prep room, lead to the exact opposite-to pockets of disguised idleness and to degradation in the overall performance.

I must say they followed with interest, asked a lot of questions, and listened attentively to my more and more elaborate explanations. Not just the Brits; Trumann and Doughty were no less attentive. I think I scored some points with them.

After five hours of grilling, we left, leaving behind homework—about three inches of financial reports. Only in the next meeting will the battle about terms and conditions start. But that is Trumann and Doughty’s headache. I will not have to participate. If they are successful at bringing the prospect to agree on the framework of the deal, the prospect will send his examiners to the company. That is when Pete’s headache will start.

“Shall we meet in half an hour in the bar?” Trumann suggests as we reach the hotel.

Good idea. I certainly can use a quick pint. Or two. Reaching my room, I try to call Don. Since European hotels are taking four hundred percent markup on telephone calls, I use my calling card. Three long strings of numbers, two mistakes and finally Don is on the line.

“Anything new?” I ask.

“What do you want to hear first?” Don is cheerful. “The good news or the bad?”

“Start with the bad.”

“The bad news is that you were wrong in assuming that Pete would have problems presenting his new offer to his customers.”

“I didn’t think that Pete would have problems presenting his offer,” I laugh. “I thought that his customers would have problems accepting it. So the bad news is that I was wrong, and the good news is that Pete was right?”

“Precisely. Pete claims that they were quite enthusiastic. He can’t wait to tell you how well it went. Why don’t you give him a call?”

I forgot to use the pound key, so five minutes and more than thirty digits later, I reach an enthused Pete.