Italian All-in-One For Dummies (156 page)

Read Italian All-in-One For Dummies Online

Authors: Consumer Dummies

On the other hand, the very meaning of

piacere

,

liking,

lends itself to the imperfect because liking tends to be ongoing, unconfined by time. Rarely do you like something only between 2 and 4 p.m. when it wasn't raining, for example. Once again, context is everything.

Take this example:

Da bambino, gli piaceva andare al cinema il sabato

(

As a child, he liked going to the movies on Saturdays

). This sentence has two clues that you want to use the imperfect:

As a child

indicates an ongoing time, and

Saturdays

indicates that this action was a habitual one.

Other words that indicate habitual action are

ogni

(

every

),

spesso

(

often

),

qualche volta

(

sometimes

),

sempre

(

always

), and

non . . . mai

(

never

). For example:

Ci piaceva guardare la televisione ogni giorno

(

Every day, we liked to watch TV

).

Here are a couple of additional examples of the imperfect:

Ci piacevano gli animali.

(

We liked animals.

) (

We have always liked animals.

) Here, the speaker is talking about something they've always liked, as opposed to the animals they saw at the zoo this afternoon.

Le piaceva nuotare.

(

She liked swimming.

) Again, you're saying that this is something she has always liked.

Recent pluperfect

The recent pluperfect (to distinguish it from the remote pluperfect, or preterite perfect), or past perfect (

era piaciuto/a, era dispiaciuto/a

[singular] or

erano piaciuti/e, erano dispiaciuti/e

[plural]), follows the same rules as the present perfect in the preceding section. The only difference is in the helping verb, which you use in the imperfect rather than the present (

era

instead of

è,

and

erano

instead of

sono

). The pluperfect refers to something that had happened, often before another event being discussed. In English, you may say,

He had finished the first book before he began the second.

The first verb,

had finished,

is in the pluperfect; the second,

began,

is in the present perfect.

Likewise, you distinguish the pluperfect from the imperfect by asking the same questions: “What had happened? What had he done?” In the case of

piacere,

“What had he liked?” It refers, in other words, to something that occurred and is over.

For example:

Non gli era piaciuto il libro

(

He hadn't liked the book

). A further elaboration may include the phrase

when he read it the first time.

Non gli erano piaciute le poesie di quello scrittore

(

He hadn't liked that writer's poetry

). If you are eager for more on past tenses, check out

Chapter 1

in Book V.

Looking at Other Verbs that Work Backward

Several Italian verbs work the same way as

piacere

â that is, backward and with accompanying indirect object pronouns. Some of them make more sense than others, as you find out in the following sections.

A few other verbs similar to

A few other verbs similar to

piacere

that aren't included in the next sections include

dare fastidio

(

to bother; to annoy

),

disturbare

(

to bother

), and

servire

(

to serve

). These verbs work similarly to

piacere

when used to speak or write.

Verbs that carry the indirect object in their constructions

Those that make the most sense are

bastare

(

to be enough

),

sembrare

(

to seem

),

importare

(

to be important

), and

interessare

(

to be of interest

). All these verbs in English carry the stated or unstated indirect object in their constructions. For example:

Two are enough for me. It seems to me. It's not important to me. It's of no interest to me.

Here are the most used forms of these verbs:

basta

basta

(

it's enough

)/

bastano

(

they're enough

)

sembra

sembra

(

it seems

)/

sembrano

(

they seem

)

importa

importa

(

it's important

)/

importano

(

they're important

)

interessa

interessa

(

it's of interest

)/

interessano

(

they're of interest

)

The indirect object pronoun is

The indirect object pronoun is

always

stated with these verbs. As with

piacere,

it precedes the conjugated forms. The following examples show how they work. They really aren't so different from their English counterparts; the main difference is that, in English, you don't usually add the indirect object.

Mi basta un esempio.

(

One example is enough for me.

)

Ti bastano dieci giorni?

(

Are ten days enough for you?

)

Mi sembra sincero.

(

He seems honest to me.

)

Non mi sembrano veri.

(

They don't seem real to me.

)

Non mi importa.

(

It's not important to me.

) (

It doesn't matter.

)

Non mi importano le regole.

(

The rules don't matter to me.

)

Non gli interessa.

(

He isn't interested in it.

) (

It's of no interest to him.

)

Ci interessano.

(

We're interested in them.

) (

They're of interest to us.

)

The verb mancare

One other fairly common verb that works backward is

mancare

(

to miss

). For example:

I may miss my friends; you may miss your family; the cat misses his owner.

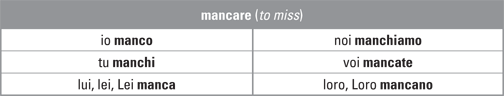

The conjugation of the basic verb

mancare

is regular, as you can see in the following table.

But the translation includes the added prepositions

to

or

by,

as in

I am missing to

or

I am missed by.

In other words, you, they, I, he, and we, for example, are missing

to

someone. To put it more idiomatically, they're missed

by

someone. If I miss my friends

Mi mancano

(

I miss them

)

or (

They are missed by me

). If you say to someone

Ti manco,

you may sound more coy than you want because it means

You miss me

or

I am missed by you.