Italian All-in-One For Dummies (143 page)

Read Italian All-in-One For Dummies Online

Authors: Consumer Dummies

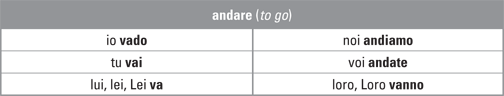

To Make or to Do: Conjugating Fare

In its most basic form,

fare

means

to make

or

to do.

With

essere

(

to be

) and

avere

(

to have

), it's one of the most versatile and useful Italian verbs.

Fare

is also one of the most idiomatic verbs. Dozens of idiomatic expressions use

fare

as their base; you can find a useful list of

fare

expressions in the later section “

Using Irregular Verbs in Idiomatic Expressions

.” See the following table for the conjugation of

fare.

Fare

can stand alone in its irregular state. For example:

Io non faccio nulla di interessante

(

I'm not doing anything interesting

). A common question used by a parent speaking to a child is

Cosa fai?

(

What are you doing?

), though friends also use it to ask

What are you doing? What are you up to?

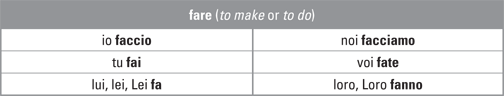

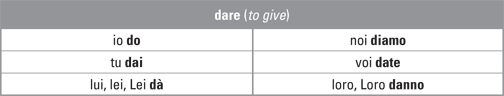

To Give: Dare

Dare

(

to give

) isn't terribly irregular. It follows the conjugation pattern of the

-are

regular verbs, with the exception of the

loro

forms, which double the consonant

n.

Dai

(

you give/are giving

) can also mean

come on!

in Italian and is pronounced like the English

die

.

The third person singular form of

The third person singular form of

dare,

dÃ

(

he/she/it, gives

or

you

[formal]

give

), carries an accent to distinguish it from the preposition

da

(

from; by

), without an accent.

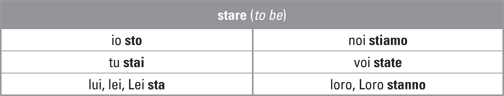

To Ask How Others Are: Stare

You use

stare

to ask how someone is:

Come stai?

([familiar]

How are you?

) or

come sta?

([formal]

How are you?

) It can also mean

to stay,

physically, somewhere.

Sto all'Albergo Magnifico

(

I'm staying at the Magnifico Hotel

);

Sto a casa

(

I'm staying home

). Accompanied by the preposition

per,

it means

to be about to.

Sto per mangiare

(

I'm about to eat

).

Like

dare,

stare

isn't as irregular as some verbs in that it follows the conjugation pattern of the

-are

verbs, with the exception of the

loro

forms, which double the consonant

n.

Stare

Stare

has one other extremely important use. It combines with a verb's present participle (

-ing

form, like

eating, sleeping,

or

reading

) to make up the

present progressive verb tense.

As serious and confusing as that sounds, it's pretty much still the present tense; it's simply a little more immediate. For example, if someone calls and asks whether he's interrupting, you may say

Sto Âmangiando

(

I'm eating

[right now]

).

You form the participles of verbs by dropping a verb's traditional or identifying ending and substituting

-ando

for

-are

and

-endo

for

-ere

and

-ire.

Here are some examples:

Sto mangiando.

(

I am eating.

)

Stiamo parlando.

(

We are talking.

)

Stai leggendo.

(

You are reading.

)

State partendo.

(

You are leaving.

)

Sta pulendo.

(

He/she/it is cleaning.

)

(

You

[formal]

are cleaning.

)

Stanno vivendo.

(

They are living.

)

(

You

[formal]

are living.

)

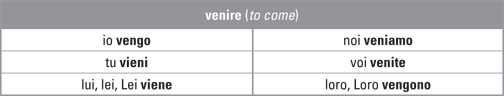

To Come and to Go: Venire and Andare

“What is all this coming and going?” asks a worried Rodolfo from the opera

La Bohème.

Coming and going are so much a part of daily activity that the verbs

venire

(

to come

) and

andare

(

to go

) are terrifically useful. And, grammatically speaking, it's safe to say that figuring out how to use both verbs is pretty straightforward â but still irregular.

Venire

(

to come

) is the opposite of

andare.

Vieni alla festa?

(

Are you coming to the party?

);

Vengono

(

They are coming

). Other verbs also mean

to go,

such as

partire

(

to go,

as in

to leave for a trip

) and

uscire

(

to go out

).

Uscire

has its own section later in this chapter.

Andare

refers to going to a particular destination or to leaving. For example, you can say

Vado via

(

I am going away

) or the emphatic, and slightly petulant,

Me ne vado

(

I'm getting out of here

). You can also say, simply,

Vanno a teatro

(

They are going to the theater

);

Vai in ufficio?

(

Are you going to the office?

); or

Non vado a scuola oggi

(

I'm not going to school today

).

A useful expression that takes

A useful expression that takes

andare

is

andare di male in peggio

(

to go from bad to worse

). For example:

La situazione va di male in peggio

(

The situation is going from bad to worse

).

Check out the following conjugations for

venire

and

andare.