It Takes a Village (11 page)

Read It Takes a Village Online

Authors: Hillary Rodham Clinton

Not long ago, on a trip to Arkansas, I ran into a man whom Bill and I had known some years earlier. He had never graduated from high school but was a hard worker who made a living cooking, catering, painting, and doing odd jobs. He had recently become a father, and I asked him if he was enjoying talking to his baby daughter. He reminded me that he was quiet and shy by nature, not one to converse much with anybody, let alone an infant. “I'd feel like a fool talking to someone who wouldn't understand a word I was saying,” he said. “Anyway, I wouldn't know what to talk about.”

I suggested that he and his wife tell their daughter about their experiences during the day, or what they were watching on television, or even the trees, flowers, cars, and buses they could see as they walked down the street.

He looked a little uncertain, but he promised to try.

I could understand his uncertainty. Much as he loves her, his baby will not consciously remember the details of his earliest attentions to her. Even older children remember selectively; the details we treasure are not always those that made the greatest impression on them. But the time we spend with childrenâand what we do with itâis more than an indulgence for parents. It is an investment in children's futureâan investment we can't make up later. As psychiatrist and writer Robert Coles has said, “Children who go unheeded are children who are going to turn on the world that neglected them.” But children who get the early attention they need, from the family and the village, will repay our efforts a thousandfold, in the strong bodies, minds, and characters they carry into the future.

Health is number one. You can't have a good offense, a good defense,

good education, or anything if you don't have good health.

SARAH MCCLENDON

D

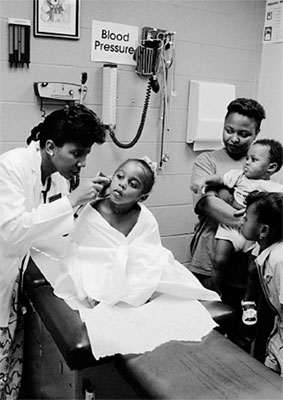

r. Betty Lowe, the medical director at Arkansas Children's Hospital, who has been president of the American Academy of Pediatrics and, most important, one of Chelsea's doctors, taught me many lessons during the past two decades. Her medical expertise and down-to-earth manner reassured me, and her common sense about preventive health care changed how I thought.

Years ago, we were both speaking to the Little Rock Junior League about children's needs. After our speeches, a woman in the audience asked Dr. Lowe what she would do to improve the health of children. Without hesitating, she replied that she would guarantee them clean water and good sanitation; nutritious food, vaccinations, and exercise; and access to a doctor when they needed one.

Dr. Lowe explained that the vast majority of children she saw in the hospital ended up there because of adults' failures to take care of them: the town that failed to clean up the sewage ditch behind some houses; the parents who failed to immunize a baby or to feed a toddler properly; the doctors who failed to accept Medicaid or treat the uninsured; the welfare worker who failed to protect a child from abuse or neglect; the landlord who failed to provide the heat promised in winter or to haul away garbage in summer; the teacher who failed to refer the belligerent or depressed teenager for help.

There's probably no area of our lives that better illustrates the connection between the village and the individual and between mutual and personal responsibility than health care. Every one of us knows we should take care of our bodies and our children's bodies if our goal is good health, and many of us try to do that. We also know, though, that we are dependent on others for the health of our environment and for medical care if we or our children become ill or injured. Knowing these things, however, does not always lead either individuals or societies to take action.

The effort to immunize children against preventable childhood diseases is a good illustration of the challenges before us. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that babies be taken for preventive checkups and receive appropriate immunizations when they are one, two, four, six, nine, twelve, and eighteen months old, then again at two, three, and four years. We've come a long way toward these goals from where we were a few years ago. Our national rate of immunization is higher than it has ever been, and as a result, we are at or near the lowest incidence ever recorded for every vaccine-preventable disease.

Some of this improvement may be due to the increased funding for immunizations and the outreach and education campaigns we have embarked on since my husband took office. We know that when funding for immunization decreased in the past, the incidence of serious disease increased. After the federal government's immunization funding was cut in the 1980s, a measles epidemic between 1989 and 1991 struck 55,000 people and killed 130 of them, many of them children. Medical costs of the epidemic exceeded $150 million, more than was “saved” by the cutbacks.

Providing funding for the inoculations themselves is key, because the vaccines are expensive and getting more so. In 1983, the private cost for a full series of immunizations was $27. Today the cost is ten times that much for just the shots themselves, and nearly as much again in administrative fees. Although nearly all managed care policies cover immunization costs, about half of conventional health insurance policies do not.

I will never forget the woman from Vermont whom I met at a health care forum in Boston. She ran a dairy farm with her husband, which meant that she was required by law to immunize her cattle against disease. But she could not afford to get her preschoolers inoculated as well. “The cattle on my dairy farm right now,” she said, “are receiving better health care than my children.”

Convenience is also a factor. Until recently, private doctors referred patients without adequate cash or insurance to the public health clinic, the only place families could take their children for free inoculations. But that doesn't mean the families went. Faced with a hodgepodge of providers, clinics' inconvenient hours and locations, and long waits, many parents delayed having their kids immunized.

In 1993, as part of a larger initiative to improve immunization rates, Congress adopted the Vaccines for Children program, which provides free vaccines to needy children through private doctors as well as clinics. The initiative also includes state funding to improve outreach and education, lengthen clinic hours, hire additional staff, and expand services. But these advances are already under grave threat from budget cuts.

We have a lot of ground to cover as it is. In immunization rates, we still trail behind a number of other advanced countries and even some less developed ones. And although three out of four of today's two-year-olds have the proper immunizations (up from about one in four in 1991), that leaves almost 1.4 million toddlers who have not received all the vaccinations they need.

Most parents are aware that immunizations are required for a child to enter school, but many of them, and even some health care providers, don't know that 80 percent of the required vaccinations should be given by the age of two. That is why the village needs a town crierâand a town prodder.

Kiwanis International, the community service organization, has been both, working to promote the needs of children from prenatal development to age five through an international project called Young Children: Priority One. Among other efforts, the project has launched a national public education campaign, which features my husband on billboards and in public service announcements calling for “all their shots, while they're tots.”

Two women I greatly admire have campaigned for more than two decades to make sure that children get the vaccinations they need, on time. Rosalynn Carter, a distinguished predecessor of mine who is compassion in action, and Betty Bumpers, the wife of the senior U.S. senator from Arkansas and an energetic advocate for children, have worked with spirit and dedication to persuade Americans to invest the money and energy necessary to ensure that all children receive their immunizations on time. When the measles epidemic began in 1989, they started a nonprofit immunization education program, called Every Child by Two, working with community leaders, health providers, and elected officials at the local, state, and national levels to spread the word about timely immunizations and to establish and expand immunization programs around the country.

We know that requiring children to show proof of immunization before they enter school guarantees that children get their shots by five or six. States and cities looking for similar ways to ensure compliance for toddlers are linking immunization efforts to social service programs. A program in Maryland requires families on welfare to show proof of immunization in order to receive benefits, a requirement I have long advocated. Recent studies in Chicago, New York, and Dallas show that coordinating immunization services with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) significantly improves immunization rates.

If we can see to it that cows get their shots, we can see that kids do tooâbefore the cows come home.

Of course, cows don't cry at the sight of hypodermic needles. It takes more than a village to persuade children that the sting of a shot is really in their interest. It helps to explain to the child in advance what the shots do, perhaps by illustrating it with her favorite dolls and stuffed animals. I know parents who take a favorite teddy bear to the doctor's office to have its “shots” as well. That allows the child to commiserate with the bear when the needle is applied, and the bear to sympathize with the child when her turn comes.

Â

P

EDIATRICIANS

recommend that children continue to get checkups at five, six, eight, and ten years. From the age of eleven on, the most explosive period of growth after infancy, they should be examined yearly. Between checkups, there are steps each of us can take to keep children healthy. From basic hygiene habits like frequent hand washing to healthier eating and exercise, prevention works.

Let's talk first about food, as we love to do. This country dreams of food, thinks about it constantlyâlemon tarts shimmering under meringue, ribs drenched in barbecue sauce, golden-brown fried chicken, mashed potatoes swimming in butter, and mile-high chocolate pies, beckoning us to indulge, indulge, indulge.

Our passion for food is a national obsession, and so is our guilt over it. Pick up a magazine or listen to the punch lines of talk show comedians, and you are left with the notion that America's conscience is concerned chiefly with diet and weight. And with some reason: One in three adults is overweight, up from one in four during the 1970s. And one in five teenagersâup from fewer than one in sevenâis overweight or close to becoming overweight, according to a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control between 1988 and 1991.

At the same time, it is estimated that one in twelve American children suffers from hunger. So while we will focus here on avoiding the health problems brought on by eating too much and exercising too little, let's not forget those among us who have too little on the table to begin with. It is critical that we continue to give nutritional assistance, especially to pregnant women, infants, toddlers, and schoolchildren, through government programs like WIC, food stamps, and school lunches.

Â

I

GREW UP

in the “clean plate” era. Today I look back at my family table, circa 1959âthe pot roast and potatoes piled high and spilling over the edges of our platesâand see a catastrophe of calories, whose consequences my brothers and I avoided during childhood by walking or biking back and forth to school and around town and playing hours and hours of sports. We were expected to eat all of whatever we were served. If we balked, we heard, like a broken record, stories about starving children in faraway lands who would gladly eat what we scorned. My brother Hugh became a champion cheek-stuffer. Tony offered to mail his food to any country my father named. In the end, we ate whatever we had to in order to be “excused” from the table.

As with so many other aspects of family life in recent decades, the pendulum has swung to the other extremeâin this case, from the “clean plate” theory of nutrition to the “no plate” one. Many families rarely sit down to even one daily meal together at a table in their home. It's easier to grab a doughnut on the run in the morning, a burger and fries at lunch, and then for dinner to graze on takeout, with one eye on the TV.

The majority of adults and teenagers, who do not drink excessively or smoke, can go a long way toward safeguarding their long-term health through diet and physical activity. As Dr. C. Everett Koop, the former surgeon general, has said, “If we could motivate the public to focus on achievable and maintainable weight, we would have taken a very significant step toward preventing one of the most common causes of death and disability in the United States today.”

It is far easier to begin good nutrition in childhood, when parents largely determine their children's diet and the eating habits of a lifetime are established. It's important, however, that diet not become a household mania. Every parent knows that children go through “eating phases,” which they will outgrow and the rest of us must endure. When Chelsea was in preschool, there were a few weeks when she would not eat anything for lunch but green grapes and a grape jelly sandwich on white bread. After a few days of observing her class, a worker from the state's child care licensing division asked the head teacher why the parents of the curly-haired blond girl sent her to school every day with such an inadequate lunch. The teacher refrained, thankfully, from naming the parents and assured her that she would talk to them.

Most of us are more relaxed than our parents were about exactly what our kids eat and how much, but a greater leniency should not become an excuse for poor nutrition. Despiteâor maybe because ofâall the nutrition information bombarding people every day, there is a lot of confusion about what to feed ourselves, let alone our kids. Even in the face of good information, we may be resistant to change. Head Start teachers have told me that after they'd taught children about healthy foods, some parents complained that they couldn't afford the foods their kids requested or that they just didn't “eat that stuff” in their house.

Good nutrition does not have to be expensive. As part of the Shape Up America! program he started, Dr. Koop recommends making healthy eating a permanent part of a family's way of life, not an occasional “diet.” There has been a revolution in the past decade when it comes to information about food, and many of us now grasp the basics: we should be eating more grains, beans, fish, fruits, and vegetables and less meat, fat, and sugar. We should encourage our families to fill their plates with a moderate amount of foodâa sensible meat serving, for example, is about the size of a deck of cardsâand to refrain from seconds. New nutrition labels help us choose lower-fat milk and cheese and select other products that are lower in fat as well as higher in fiber. Many restaurants offer healthier alternativesâlean or “spa” cuisine.

We need to teach children to take responsibility for their own weight, rather than passing the buck to genetics or a slow metabolism. Although diet is not an exact science, and we differ in the amounts and kinds of foods we can healthily consume, these physiological factors account for only a small number of overweight people. Most of us (including me) simply exercise too little and eat too much.