IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done (4 page)

Read IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done Online

Authors: Bill Holtsnider,Brian D. Jaffe

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Information Management, #Computers, #Information Technology, #Enterprise Applications, #General, #Databases, #Networking

Pros and Cons of Being a Manager: Reasons to Become a Manager, and Reasons Not to Become One

The Hidden Work of Management

One challenging aspect of management is that the actual work done is often less apparent and less tangible than the work being done by subordinates.

Management Is Sometimes Hard to See

There are, of course, examples of useless and lazy managers. You may even be a victim of one. But management is not, in and of itself, easy. Nor are all of its components visible. A worker may see a manager spend several hours a day in meetings: “That guy just spends his days in meetings, and doesn’t do any ‘real’ work.” But the truth is probably quite different: The manager may be attending those meetings with fellow managers and performing some of the tasks discussed in this book: reviewing resources, discussing personnel matters, proposing or defending a budget, setting objectives and strategies, fighting with Human Resources (HR) and Finance about planned layoffs, or planning a system overhaul. In that scenario, a hard-working manager and a slouch look exactly the same to an outside observer.

Good and Bad Management Often Look Alike—For a While

In addition, because great—or even good—management is often hard to see, the effects of good management are sometimes clear only in retrospect. Consequently, bad management and good management can look the same until the outcomes are seen. A manager that has a critical meeting with a subordinate that gets that subordinate back on track looks, to the outside observer, exactly like a manager having an intense conversation with a coworker about weekend party plans. That worker’s new attitude may take weeks, or months, to show itself concretely. A key decision not to pursue opening a new plant overseas happens in meeting rooms far from the general employee population; it may cost hundreds of jobs in the short term, but save thousands in the long term. Those results will show up in the financial results years after the decision was made.

Resentment toward Management

If you become a manager, you can assume there may be some resentment toward you in that role. This resentment could be because others in the department had hoped that they would get the job or some may think that you’re not qualified. There are also challenges when you are promoted and now have to manage a group of people that used to be your peers. There can be a tendency for tension between non-managerial staff and managers: The role of one is to direct, steer, or manage the other. Most of the time, that relationship works well and each person knows her own role and understands the other’s role to some degree. Occasionally, however, that tension needs time and attention by both sides before it disappears.

The key to dealing with this problem is to communicate. Talk with your staff. Build a relationship with

each

member of your team. Let each person know you recognize their talents and their contributions.

Babysitting versus Managing

There is a portion of any manager’s job that is “just babysitting.” People are unpredictable, but you can predict they aren’t always going to act in ways that will help you and your department. Sometimes their actions will cause you a great deal of stress; anyone who has had to lay off employees will attest to the pain of delivering a pink slip. Some of your staff will do exactly as you request, which may mean they sit idle until you request something. Others are so eager to do more that you have to hold them back. Other times employees will drive you crazy with items so mundane you’ll scarcely believe you are talking about the issue. Many managers know of the enormous “turf wars” that erupt over inches of desk size, who gets the larger monitor, or who is allowed to go to which training classes. Hence the name “babysitting.”

Politics

Unlike non-managerial workers, many managers spend a large amount of time dealing with the political elements of the company. While some people dislike any form of politics at work, many others thrive on it. “Politics at work” can mean anything from jockeying for a larger role in an upcoming project to turf wars about who manages which department.

Some politics is necessary: the network support team needs someone to run it, and either a new person has to be hired (see

Chapter 3, Staffing Your IT Team

on

page 65

) or a current employee needs to be appointed. Since people are only human, some subjective considerations will eventually come into play. Does John in Accounting have the right personality for the job? If Mary is given that promotion, will she eventually merge the department with her old one? If Tom is hired, will he want to bring along his friend Chris that he always seems to have working for him?

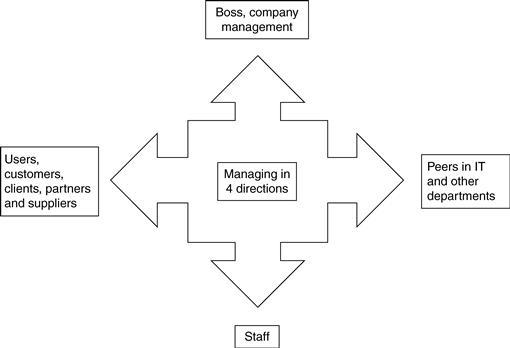

Managing in Four Directions

Chapter 2

, Managing Your IT Team

on

page 31

, is dedicated to the issues of managing your staff. However, it is important to note that most managers have to manage in four directions (see

Figure 1.1

). Although managing your team is probably the most vital of these four and will consume a good portion of your time and energy, you cannot ignore the other three.

•

Managing up:

This includes your boss and other company management.

•

Managing your peers:

Your peers include people at the same level as you within the organization. This can be other managers in the IT department, as well as managers in other departments.

•

Managing your users/customers/clients:

These are the people to whom you deliver your services. They could be users calling your Help Desk, customers using the company website, employees accessing e-mail or file-servers, or partners you exchange data with.

•

Managing your staff:

These are the individuals (employees, consultants, even vendor representatives) in the organization that report into you.

Figure 1.1

Managing in four directions.

In all four of these directions, you’re dealing with similar issues: setting expectations, developing relationships, aligning goals and strategies, demonstrating leadership as well as management, and so on. However, each of them has a different twist, too. For example, you set expectations differently when you manage up than when you are managing your staff. In the former, you’re helping set a frame of reference for your management as to what they should expect, from you, from technology, and from your team. You are also outlining what you’ll need from them (support, resources, etc.). When you set expectations for your staff, you are defining objectives for them, and holding them accountable. Similarly, aligning goals is something you would do in all four directions, but you would do them with a different approach and at different levels with each direction.

1.3 The Strategic Value of the IT Department

IT has become one of the most critical functions in the economy of the new century. As corporations have embraced the efficiencies and excitement of the new digital economy, IT and IT professionals have grown dramatically in value. IT is no longer “just” a department, no longer an isolated island like the MIS departments of old corporations where requests for data would flow in and emerge, weeks or months later, in some long, unreadable report. Many companies now make IT an integral part of their company, of their

mission statement

s, and of their spending. Your role is more critical than ever before.

The CEO’s Role in IT

First, the CEO must be sure to regard information technology as a strategic resource to help the business get more out of its people. Second, the CEO must learn enough about technology to be able to ask good, hard questions of the CIO and be able to tell whether good answers are coming back. Third, the CEO needs to bring the CIO into management’s deliberations and strategizing. It’s impossible to align IT strategy with business strategy if the CIO is out of the business loop.

—Bill Gates

Business @ the Speed of Thought

Application Development versus Technical Operations

Most IT organizations have two primary functional areas: Applications Development and Technical Operations.

Application Development

Companies often see the real value of IT as only the applications that serve the company’s core business. Applications are what allow one business to become innovative, more efficient, and more productive and set itself apart from its competitors. Careers within applications development include analysts, programmers, database administrators, interface designers, and testers, among others.

Many people within IT like working in application development because it allows them to learn how the business operates. As a result, it may often provide opportunities for increased involvement with people in other departments outside of IT. However, many programmers find the job is too isolating because their daily interactions may only be with the program logic displayed on their screen and the keyboard; they don’t like being only “keyboard jockeys.” Of course, other programmers welcome the isolation and embrace the opportunity to work in relative seclusion.

Technical Operations

The technical support function is the oft-forgotten area of IT. The Technical Operations organization is responsible for making sure that the computers are up and operating as they should. Their jobs go well beyond the computer hardware and include the network (routers, switches, telecommunication facilities, etc.), data center, operations, security, backups,

operating systems

, and so on. The Help Desk may be the most visible portion of the Technical Operations group. Within the industry, this infrastructure side of IT is often referred to as the “plumbing.” Like most important and underappreciated jobs, when Operations is doing their job well you don’t even know they exist. But if something goes wrong, their visibility within the organization suddenly skyrockets.

However, those working in Operations may find the time demands stressful. Some system maintenance can be done only during weekends and evenings when users won’t be affected. Similarly, it will be the Operations staff that is roused by a mid-REM-sleep phone call when the system crashes in the middle of the night. (For a discussion of methods of preventing burnout, see

Chapter 2, Managing Your IT Team

on

page 31

.

)

IT Department Goals

One of your objectives as an involved and caring manager is to make sure that your department’s goals are in line with those of your organization. It doesn’t matter if you’re an IT Manager for a small nonprofit or a midlevel manager for a Fortune 500 company, you need to discover what the organization’s goals are and make them your own.

If you work for a corporate organization, your IT goals may be measured in the same terms as the business areas that you support—reduce per-unit costs of the division’s products and increase the capacity and throughput of the business and manufacturing processes, for example. Your tactics must clearly satisfy these goals. If you work in a nonprofit or educational organization, your goals—and the way you are measured—will be different. Your boss should be clear about communicating those goals to you—they shouldn’t be a secret.

The Value of IT Managers

IT is a complex, misunderstood part of many of today’s organizations. Executives now know how to use Word, Excel, e-mail, their smart phones, and how to mine the Web for information, but some have little or no understanding of the deeper, more complex issues involved in IT. They imagine IT to be a powerful but multifaceted world where rewards can be magically great and risks are frighteningly terrible. These executives and their corporations need professionals to both explain and execute in this world. This is where you come in.

You can leverage your technical knowledge, experience, and interests with your company’s direct profit and loss requirements.

Together

, you and your company can provide a powerful business combination.

Alone

, your individual skills and passions can wither into arcane interests, and your business expertise can build models relevant to an economic world decades in the past.

•

Will your technical expertise and recommendations occasionally clash with the company’s needs and vision? Absolutely.

•

Will your ideas about technical directions sometimes be in direct opposition to others’ perceptions of “market forces”? Absolutely.